THIS ISSUE

of the Changjin Journal we continue our review of the Marine Corps

pamphlet titled FROZEN CHOSIN: U.S. Marines at the Changjin Reservoir, by retired

Marine historian BGen Edwin H. Simmons

. This journal will be presented as filler material to that already published in the

pamphlet. See Changjin Journal 11.11.04 for part

two of this review series. And

See Changjin

Journal 10.10.04 for part one of this review series.

FROZEN CHOSIN

The Marine Corps publication FROZEN CHOSIN continues to be an interesting read.

Noted is the heavy slant toward the Corps which relates to the masthead, that this

publication "is published for the education and training of Marines ... as part of

the DOD observance of the 50th anniversary of that war." We regret that at times

the coverage of attached units of other services seldom reports accomplishments.

COMING OUT OF YUDAM‐NI

P.79 We have long wondered about the command arrangement for Yudam‐ni

forces, a situation in which there was not one designated commander, but an apparent

cooperative effort between two regimental commanders, a colonel and a lieutenant

colonel. In normal command arrangements, the senior officer took command or was

designated by higher HQ as the commander. Here we learn about "Litzenberg and

Murray" organizing a provisional battalion, and then "Litzenberg and Murray

issued their second joint operation order." If this operation had turned into a

debacle similar to the other side of Chosin, who would have been held

responsible?

Although the 155 guns and prime movers had to be abandoned because they ran out of

diesel fuel, we have never seen end‐reports from either side reporting that they

had been destroyed the following day. Knowing the Chinese concern about using the

battlefield as a supply depot, imagination tells us they would have camouflaged the

equipment until they themselves could haul off such a treasure of weapons.

Did this command arrangement contribute to the success of this phase of the

breakout, or was it the fact that the enemy never did have the capability of stopping

them? Interesting, to say the least, especially when the reader reads the final pages

(p.124) of this monograph and learns about the limitations of the Chinese divisions

encountered at Chosin. If readers chart the friendly casualties day by day from the

first CCF attacks to the end of the campaign, they will find a distinct relationship

between the daily losses and the reduced capabilities of Chinese forces.

P.84 When the 5th Marines left Yudam‐ni "led by a solitary Pershing

tank," we wonder if that was a joint decision since we know that tanks were placed

at the end of the column when they broke out of Koto‐ri. Readers interested in

understanding the breakout along the road in more detail should make use of a 1:50,000

topographic map, rather than the sketch map on p.44. Understanding is also enhanced by

reading the captions accompanying the many photographs. On this page we read that the

large number of road‐bound vehicles ... slowed the march and were a temptation

for attack by the Chinese. Since all vehicles were road‐bound in that terrain,

they hardly slowed down the pace of the infantryman who was humping the ridges above the

road. More than carrying the "wherewithal to live and fight," they carried the

wounded and the dead.

p.86 The cross‐country trek by Lt. Col. Ray Davis and his 1/7 Marines to

reach Fox Hill reminds us again of the limited capability of the Chinese who were

operating in terrain and weather entirely foreign to them, doubting also that they had

maps as well as compasses and flashlights to help navigate at night in a snowstorm.

Winter warriors of history understand ways of taking advantage of terrain, as Davis did,

that of doing the unexpected which in this case was enhanced by a snowstorm. We are

reminded that leaders and commanders must expect extreme reaction from men under their

command when facing difficult conditions, be it enemy or weather. During the extremes of

battle, we know not all men are created equal. Having but one killed in action, and that

happening at the Fox perimeter, once again reveals the friendly advantage over the enemy

disadvantage. The Chinese didn't know what was happening and didn't have the

capability of doing anything about it.

REORGANIZATION AT HAGARU‐RI

p.88 Almond decorated Smith, Litzenberg, Murray and Beall at Hagaru with Army

Distinguished Service Crosses, then later at Koto‐ri decorated Puller and

"Reidy (who had been slow at getting his battalion to Koto‐ri)" with

the DSC. Why is Reidy accused of being "slow," with no explanation, when the

problem was that of X Corps providing trucks for his battalion? Almond obviously learned

this at Hungnam or he certainly would not have decorated Reidy.

DESTRUCTION PLAN

p.89 Reading a "destruction plan ... the disposal of any excess supplies and

equipment" will remind those who had been at Hagaru‐ri that vast quantities

of all types of supplies were to be destroyed. We recall cargo falling out of the sky on

5 December, day before the breakout, some being dead drops that killed men asleep in

warming tents. After that loud warnings were sounded when aircraft arrived overhead,

eyes alert as the parachutes burst open with cargo swinging in sudden gusts of wind. One

can but wonder what the CCF scouts on the high ground surrounding Hagaru‐ri were

reporting to their commanders, as well as frustrations felt because they didn't

have the capability of bringing down heavy mortar fire on thousands of soldiers and all

that equipment. Once again the Chinese supply lines had run dry as the Chinese

commanders began planning to resupply after the exodus of its oversupplied enemy.

p.90 Also falling out of the sky were the 500‐pound bombs from a B‐26

bomber which frightened the hell out of the occupants as they slashed open the tent

sides creating the most direct route to the nearest shelter. The Americans were most

fortunate that the Chinese had run out of heavy mortar ammunition, or probably their

base plates were shattering due to the intense cold.

HAGARU‐RI TO KOTO‐RI

p.91 The "plan of attack" called for the 5th Marines to take care of the

East Hill problem while the 7th Marines led the attack down the road ñ as simple as

that. However, there may have been wishful thinking in the development of this plan,

probably because the enemy did not threaten Hagaru‐ri or Koto‐ri. Why were

they so quiet? The breakout plan called for a "flying wedge," as Al Bowser

called it later, with one battalion of the 7th Marines leading and another echelon on

the right, while the Army provisional battalion 31/7 would be extended on the left. Why

this arrangement? Was it because the Army had been east of Chosin while the Marines had

been on the west? If not, why was the weakest force 31/7 given the side that not only

gave Drysdale the biggest problem, but which, from a terrain study, identifies the most

probable locations for enemy blocks.

This was Division's first breakout plan. From Yudam‐ni it had been a

joint plan by Litzenberg and Murray (approved by Smith), while east of Chosin there had

never been a plan. First, there were no assigned objectives or phase lines established

for control. It was normal to have terrain features suspected as having enemy positions

identified as objectives and drawn on overlays issued with the operation order. This

simplified the issuance of orders as well as control during the attack. Phase lines to

control the forward movement of units were also handy. These did not exist in this

attack that took place during daylight and the dark of night, making it extremely

difficult to control. This was admitted to be an error in planning by the late Lt. Gen.

Al Bowser during a reunion in 1990, adding that objectives were used in the next attack

order, from Koto‐ri south.

LESSONS LEARNED

p.91 We read that "this time they faced the lurking presence of seven CCF

divisions?" identified by PW reports, plus two more unconfirmed divisions, units

reportedly moving south as far as "the dominating terrain feature, Hill 1081, in

the Funchilin Pass." These assumptions do little to add reliable information about

the enemy to the story, although they do hype the story. Needed are the probable enemy

unit strengths and locations between Hagaru‐ri and Koto‐ri. Only one

accurate assumption was available, that the enemy faced Drysdale in Hell Fire Valley.

Nowhere do we read about massive preparatory fires being delivered on likely enemy

positions. Had registrations been fired and plotted for the forward observers? These are

the types of questions that come to mind by veterans and historians interested in

details of a specific battle, the answers of which provide the basis for lessons

learned.

In preparation for the East Hill attack by the 5th Marines we read that heavy air,

artillery, and mortar preparation began at 0700 on Thursday, 6 December." Those who

were there may question the availability of tactical air at that early hour, knowing

that air support for the first major attack against a strong Chinese position a few

kilometers south of Hagaru‐ri had to wait hours for a break in the

weather.

RCT 7 ATTACKS SOUTH

p.92 The description of the breakout from Hagaru‐ri is hardly correct. As

reported here the lead unit of 2/7 Marines ran into trouble on the left, "air was

called in [for a] showy air attack ... against the tent camp south of the

perimeter," after which the lead companies pushed through and the advance resumed

at noon. An accurate description of that action is contained in CJ 02.28.03 which

involved the lead Army provisional company "I"/31/7 with air and mortar

support attacking the first enemy position on the left which had cut the 2/7 Marines

column, resulting in the capture of 115 Chinese soldiers. The air strike (photo p.93)

was not against the tent camp, but against the Chinese position on the ridge to its

left. The Marines in the photo are watching not only the "showy air attack,"

but also the movement of provisional Item Company along the high ground to the left and

its final assault on the Chinese position. All of this could be seen from this position

along the railroad track, yet was never reported in official military publications. We

continue to question a subsequent action reported as "an Army tank solved that

problem." The only Army tanks in the area were Drake's 31st Tank Company, and

it was attached to the 5th Marines to serve in the rear guard of the breakout from

Hagaru‐ri.

AT KOTO‐RI

p.94 The apathy shown by a battalion commander with resulting diagnosis of neurosis

causing his relief is important for readers to understand. The Chosin campaign was full

of intense combat actions over long periods without rest, bringing most participants

very close to the breaking point. This was seen by Beall during the breakout east of

Chosin where some men on the ice were "walking in circles." Post traumatic

stress has never been adequately addressed in publications about Chosin, while

participants have learned that the disorder ñ PTSD ñ can appear decades later. To this

day, some survivors of Chosin avoid attending reunions.

p.96‐7 Once again we note the reduction in friendly casualties (103 KIA out

of a force of 10,000) from Hagaru‐ri to Koto‐ri which continues to

emphasize the reduced capabilities of the Chinese divisions reported as being in the

area. This reduced capability is further emphasized by the fact that more than 14,000

troops were jammed into the Koto‐ri perimeter, yet the enemy was not able to fire

one round on this lucrative target. Chinese soldiers were seen each day on high ground

off in the distance just watching.

MARCH SOUTH FROM KOTO‐RI

p.97 Details of the two companies making up Bob Jones' mini‐battalion

can be found in Changjin Journals 05.01.03 and 07.10.03. Capt. Rasula is described as

"a canny Finnish‐American from Minnesota who knew what cold weather was all

about."

OVERSNOW MOBILITY

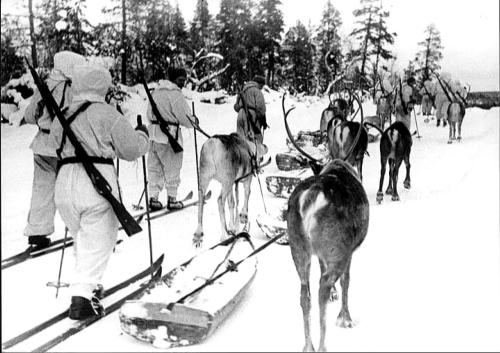

Readers are reminded that the northern third of Finland is reindeer

country which rests north of the Arctic Circle, a landscape of severe cold during early

1940 when, as in this photo, Finnish troops used the mobility of the locally available

reindeer to pull the ahkio. ‐‐ Photo courtesy History Department,

Finnish Defense Forces

.

RASULA REMEMBERS

My military connection to winter warfare came when stationed at Fort Lewis,

Washington with the 9th Infantry, 2ID, late 1947 when a group of former Finnish army

officers joined us to participate in Exercise Yukon to Alaska. As fate would have it, I

became interpreter for this group and trained with them through mountain training

followed by the exercise that took us via C‐82 aircraft to Fort Greeley and Nome.

The first "ahkio" to be used by the U.S. Army, a boat‐shaped sled to

replace the old 10th Mountain Division sled, was handmade by these Finns for the

exercise. For me, this was not only training in the basics for combat in a winter

environment, but also an advance course based on the winter war fought by the Finns

against the Russians (Soviets). From Colonel Alpo Marttinen, then an Army private, I

learned the details from his personal maps about the famous battle of Suomusalmi during

which a Finnish division annihilated two Soviet divisions during

November‐December 1939. The late Colonel Marttinen was a recipient of the

Mannerheim Cross (Finland's Medal of Honor). I connected with another Finn, Olavi

Alakulppi, who was a medaled Olympic ski racer who coached me in the finer points of

cross‐country racing. Two years later with the 31st Infantry in Hokkaido I put

this training to good use by teaching winter warfare to the officers classes and

training a cadre. All soldiers received survival training as well as oversnow mobility

with skis and snowshoes. The advantage of the training has been announced by SSgt James

DeLong of K3/31 who was captured east of Chosin, saying he would never have survived the

long march and three years in prison camp had it not been for the training he had

received at Camp Crawford. ‐‐ GAR See CJ 08.01.02, Kiinalainen Motti: The

Chinese Encirclement.

TODAY'S OVERSNOW MOBILITY

Modern ahkio loaded with tent and other gear for squad of ski equipped soldiers.

Photo courtesy Minnesota National Guard, Fort Ripley,

Minnesota

SKIN THE CAT

p.98 The operation south from Koto‐ri is described as a

"skin‐the‐cat maneuver with rifle companies leapfrogging along the

high ground" to take the key terrain in the pass while the 1/1 Marines would attack

up the pass from Chinhung‐ni to take Hill 1081 which "dominated" the

bridge site. Here we expand our review into a critique of tactics. Apparently a planner

looked at the map and decided that Hill 1081 was about halfway down that winding road

and should therefore be the dominant terrain. That may seem logical when looking at a

flat map rather than studying the contour lines which mold the terrain. Since all of the

planning was based on the blown bridge at the gatehouse, let's keep that in mind as

we study the ground. The gatehouse is at an elevation of 1,000 meters. Hill 1081 is 81

meters higher than the gatehouse in a southeasterly direction. The ridge on which the

gatehouse is located extends upward becoming the western part of Hill 1457, being 567

meters higher than the gatehouse and 376 higher than Hill 1081, and obviously the

highest ground which dominates and has observation over all commanding terrain seen to

the south. Therefore, an artillery observer (or FAC) on the Hill 1457 hill mass has

observation over and can direct fire on Hill 1081, an ideal target for 155mm howitzers

far down the pass at Chinhung‐ni.

And finally, the blown bridge at the gatehouse is not within direct observation

(1,000 meters line of fire) from Hill 1081; it is hidden by the ridge that descends from

the west section of Hill 1457. A good photo of the gatehouse snuggled into the hillside

can be seen on page 101. With these observations in mind, we continue to wonder why the

division plan called for the 1/1 Marines to attack uphill to take an objective that did

not dominate the bridge site, rather than attack south using one of the two fresh

battalions at Koto‐ri, the 2/1 Marines or the 2/31 Infantry. See CJ 05.01.03

which contains a 1:50,000 topographic map of the Funchilin Pass.

KOTO‐RI TO CHINHUNG‐NI

p.107 This page contains an excellent photo of the dead being unloaded from a truck

and placed on the burial site after which it was covered by a bulldozer. A photo of the

burial ceremony can be seen in CJ 05.01.03.

p.108 We read that the last Marine battalion to go down the pass was preceded by

"Jones' provisional battalion of soldiers and the detachment of the 185th

Engineers." This was not the case for the two provisional companies that went down

the pass with the 7th Marines to which they were attached. On this page the reader

learns that "Lt. Col. John U. D. Page, an Army artillery officer, took charge, was

killed, and received a posthumous Medal of Honor." Once again, this Army officer

did not receive the honor of being posted on the Medal of Honor pages of this pamphlet.

Below is a photograph of Lt. Col. Page taken at Koto‐ri by his jeep driver,

Corporal Klepsig.

Army Lt. Colonel John U.D. Page (Medal of Honor) at Koto‐ri,

December 1940

‐‐Photo courtesy CWO Michael Kaminski, USA

(Ret)

p.112 The final Division statistics for the breakout from Koto‐ri,

8‐11 December, are 75 KIA, 16 MIA AND 256 WIA. These numbers plus those of the

Army provisional battalion reveal that the Chinese never did have the capability of

stopping the breakout, or even doing serious damage from Hagaru‐ri to Hungnam.

They did their most serious damage during 27 November through 1 December when they hit

the 5th and 7th Marines at Yudam‐ni and destroyed RCT 31 east of Chosin. After

that the inability of their logistics system to sustain their divisions with ammunition

for weapons as well as food and shelter for their poorly clothed soldiers permitted the

divisions of X Corps to go back on the line in South Korea much sooner than the CCF that

were involved in a losing battle. They can claim victory because they retained control

of the land, while the Marines claim victory because the Chinese failed to destroy the

1st Marine Division. During this campaign the Army paid the ultimate price with the

lives of more than one thousand soldiers, most of whom remain to this day in the soil

east of the Chosin, now called Changjin.

With this we close this issue of our Changjin Journal with the motto of the 31st

Infantry Regiment: Pro Patria ‐For Country.

END NOTES

This concludes our review of FROZEN CHOSIN.

For a copy of pamphlet FROZEN CHOSIN contact the

Chosin Few Business

Office

238 Cornwall Circle

Chalfont, PA 18914‐2318.

chosinfewhq@aol.com

For access to web issues of the Changjin Journal, go to

http://nymas.org/changjinjournalTOC.html

UNDERSTANDING AND REMEMBERING

For those who wish to read further into recent publications related to the Korean

War, we invite your attention to UNDERSTANDING AND REMEMBERING, A Compendium of the 50th

Anniversary Korean War International Historical Symposium, conducted 26‐27 June

2002 at the Old Dominion University, Norfolk, Virginia. This 210‐page pamphlet is

copyright © General Douglas MacArthur Foundation; copies are available for purchase

through the MacArthur Gift Shop, MacArthur Square, Norfolk, VA 23510.

The pamphlet contains edited transcripts of presentations by Korean and American

participants. Of interest to the Chosin veteran will be the seventh panel,

"Veterans Remember," with Chosin remembered by two Marines, GEN Ray Davis and

BG Ed Simmons. We had learned that LTG Bill McCaffrey had been invited but was not able

to attend.

END CJ 12.12.04