CHANGJIN JOURNAL

CHANGJIN JOURNAL 10. 10. 04

Refugees in the snow, Korea,

1950

|

|

The

Changjin Journal is designed to disseminate and solicit

information on the Chosin campaign. Comments and brief

essays are invited. Subject matter will be limited to

history of the Chosin campaign, as well as past or present

interpretation of that history.

See End Notes for distribution and other

notices. Colonel George A. Rasula, USA‐Ret., Chosin

Historian, Byron Sims, Contributing Editor

|

CHANGJIN

JOURNAL 10.10.04

THIS ISSUE of the Changjin Journal is

based on Frozen Chosin from a point of view of participating

services. In doing so it will be critical of the handling of the

Chosin story in past history where omissions in historical fact can

misdirect the reader's point of view. In the pamphlet's

132 pages the reader will view about 150 photographs and 11 maps in

addition to other illustrations. We regret that many of the maps are

not sufficiently detailed nor related to nearby text. When possible

this journal will be presented as a filler to that already published

in the pamphlet.

FROZEN CHOSIN

The newly published pamphlet by the Marine Corps titled

FROZEN CHOSIN: U.S. Marines at the Changjin Reservoir, by retired

Marine historian BGen Edwin H. Simmons, is excellent reading.

However, based on past historical writings, it does not tell the

whole story. As stated in the masthead, this publication is

"one in a series devoted to U.S. Marines in the Korean War era,

is published for the education and training of Marines...as part of

the DOD observance of the 50th anniversary of that war." We

thank General Simmons for including the Changjin Journal in his list

of sources, as well as recognition to a select few who offered

reviews of portions of the draft document in its early

stages.

At Hyesanjin on the Yalu River, left to

right, BG Homer Keifer, 7th DivArty commander; BGen Henry Hodes, 7th

Div ADC; MGen "Ned" Almond, X Corps commander; MGen David

Barr, 7th Div commander; and Col Herbert Powell, commander of the

17th Infantry Regiment which made it to the Yalu River on 21

November. Powell is wearing the standard pullover (reversible) parka

shell, the same as worn by other 7th Division troops who went to the

Chosin Reservoir. Gen Hodes appears to be wearing a

button‐down version of a similar reversible parka shell.

Keifer on the left is wearing a standard officer's trench coat

while Gen Barr is wearing a hooded parka similar to that worn by the

Navy and Marines. We leave Gen Almond's garment up to the

viewer, a long jacket with fur lined hood. All seem to be wearing

shoepacs, although Almond could be wearing well shined combat boots.

COPING WITH THE COLD

(p.2633)

Here we read eight pages devoted to the problem of cold during the

Chosin campaign. Of interest is the old school that believed socks

and insoles could be dried by placing them next to the body,

originating from the school of old soldiers who had no experience in

winter warfare. There had been a tendency to "fight the

cold" rather than understand what one must do to care for

himself and his equipment. The belief by some that temperatures

ranged from 35 to 40 degrees below zero is well handled by the

author by informing the reader that thermometers essential for

accurate firing by artillery recorded 20 to 25 below, as noted in

the personal memoir of General Smith.

Dealing

with the cold at Chosin is a subject that warrants more attention.

The problem that existed then was caused by the circumstances of

that day in time. Soldiers did not have "winter parkas, shorter

and less clumsy than the Navy parkas." This was a World War II

10th Mountain Division reversible parka shell, white on the inside,

that served only as a wind breaker and camouflage, relying on field

jacket with pile lining and other clothing to be worn beneath. As an

outer garment designed for ski troops practicing stem christies on

the slopes at Vail, Colorado, it was extremely impractical in the

cold at Chosin while being the only outer garment many soldiers had

to wear.

One may wonder why bundles of white bed

sheets readily available in Japan were not air dropped to provide

for improvised camouflage. Even before Chosin, research in cold

weather operations was taking place by the Army in Alaska, resulting

in far better clothing and equipment, as well as updated concepts of

operations in cold and snow, the results of which would be seen in

Korea the following winter.

[INSERT Lessons

Learned]

LESSONS LEARNED

"I find it amazing that highly trained professionals with

extensive combat experience could have approved and tried to execute

the tactical plan of operations for the X Corps in northeast Korea

in November 1950. It appears like a pure Map Exercise put on by

amateurs, appealing in theory, but utterly ignoring the reality of a

huge mountainous terrain, largely devoid of terrestrial

communications, and ordered for execution in the face of a fast

approaching sub‐arctic winter." General Matthew

Ridgeway, review comments on MS for Ebb and Flow, 27 Feb

85.

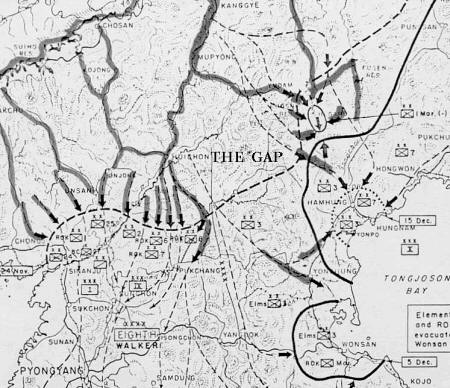

The Gap Map.jpg

Click within the map area above to see a larger image.

THE GAP

Much has been

made of the 80mile gap between the X Corps and the Eighth Army

as it continues to be discussed among Chosin veterans and

historians to this day. Why is "the gap" a problem?

Was the much larger gap between the Inchon landing and the Pusan

perimeter argued in the same light? No. Two major forces, Eighth

Army and Tenth Corps, were pursuing a beaten enemy. The argument

about the gap comes from hindsight that followed the

introduction of a new threat in the theater of operations. The

argument also involves the tendency to search for a scapegoat,

someone to blame when the participants are partly to blame for

the circumstances that were faced. Once again, one must study a

topographic map of that 80mile gap, then answer the question not

often asked: who in his right mind would use such terrain, and

if so, for what purpose? And finally, in the end, why

didn't the Chinese make use of it? There lies the

answer.

SECURITY AND THE FUNCHILIN

PASS

(p.36) Security was the operative word

at Chosin but being overcautious could tip the advantage to the

enemy. Ground reconnaissance was the key to security and often

neglected during the Chosin operation. Reports were made that

company and platoon size patrols were used to seek out the enemy

(see Patrols on p.45), when in fact it was not a recon patrol,

but a combat patrol. Ground reconnaissance can only be effective

during day or night by using small teams relying on the mobility

of the infantryman.

When no confirmed

information is available about enemy units in the area of

operations, a combat patrol will see only that which the enemy

wants them to see. Whereas a recon patrol of

well‐camouflaged men using stealth would have

accomplished as much as the North Korean or Chinese scouts were

doing when they observed the Americans. Once the enemy unit has

been located it is then time to make use of combat patrols to

contact and maintain that contact until the commander commits

forces to attack and destroy. The action at Sudong during early

November is an example of permitting a Chinese division to break

contact without being pursued.

The 5th

Marines east of Chosin sent patrols to the north and northeast,

both too large for reconnaissance purposes. Major Chinese forces

were just beyond the next mountain and within artillery range of

Marine positions. These Chinese units were on the move late in

the day when the last of the 5th Marine battalions withdrew,

attacking the arriving Army units within hours.

Security at Chosin was a guessing game. Reports based

on very few captured soldiers who identified their division were

an indicator that elements of the division were in the area.

Little is known about the specific locations and activities of

Chinese divisions and their various regiments other than results

of interrogations of a few enemy soldiers.

After‐the‐fact enemy documents and publications

remain incomplete. Details on attack plans and locations of

battalions and companies are needed to tell the complete

story.

Security also relates to the

disposition of friendly forces, especially securing bases of

operations such as Hagaruri which was a key road junction

serving units to the north and west. East Hill, actually a

mountain, was far too large to be secured by the units available

at the time. This was not the case at Kotori more than four

miles from the crest of the most critical terrain feature, the

Funchilin Pass. Most neglected was the gatehouse bridge in the

pass that apparently received some recognition but no action to

secure the site. Was this too far to the rear to be of

concern?

NEW ORDERS

(p.40) One of the most difficult problems in

understanding Chosin is the timing of plans and orders, as well

as the viewpoints of the commanders involved. The 1MarDiv had

the mission of attacking north and was urged by the corps

commander to make haste, to get going and make contact with the

enemy. This did not happen in the way envisioned by General

Almond.

On the other hand, General Smith was

concerned with the dispersion of this regiments, wanting to

gather them as close as possible considering the terrain and

build up his bases along the Chosin MSR. Today most historians

or writers look at Smith's delay as beneficial. This may be

so, although this theory comes from hindsight and does not

represent the need at the time for movement to accomplish the

mission. A war game would reveal that, within the time frame of

the movement north, two of the Marine regiments could have been

disposed from Hagaruri to the town of Changjin north of the

reservoir dam, a gap through which the Chinese moved forces

south to the reservoir.

While hastening the

movement north, the division's Reconnaissance Company and

later the 41 Commando, Royal Marines, both highly trained in

reconnaissance, could have been used to find the enemy. Had this

happened the disposition of the Marine regiments would not have

favored the plan to attack west from Yudam‐ni, but would

have envisioned the attack west from the town of Changjin, a far

greater threat to the Chinese. Bear in mind that the primary

route south by the Chinese was down the Changjin river system,

and not through the mountains west of Yudamni. The Changjin

route followed a valley with a reasonably good road, a narrow

gauge railroad and many manmade structures which offered shelter

to advancing forces. The Chinese used it. The Americans

didn't.

The Marine regiments were

eventually disposed near the south end of the Changjin reservoir

system when MacArthur came up with his plan and order to attack

through the rugged mountain range west of Yudamni at a time when

intelligence documents reported the beginning of severe winter

weather, also a time when friendly forces were unprepared in

both training and equipment to be combat effective in winter

warfare. A similar command situation had already developed in

China as they too committed unprepared armies through the same

terrain to meet the Americans. The Chinese soldier's

weapons, limited equipment and logistic system were far less

combat effective than his enemy.

TIMING

The schedule was not based on the need

to prepare and move the major units in time to execute a plan,

but rather that of wishful thinking. There is a tendency to say

the staff didn't properly brief General MacArthur on the

terrain and weather involved in such an operation; no, such

thoughts were unnecessary because most knew that MacArthur had

already made up his mind and nothing could have changed

it.

Once again we face various

interpretations of the change in X Corps plans when, in fact,

the plans originated with MacArthur. The original plan was for

the 1MarDiv to attack north on the east side of the reservoir

toward the Yalu river, a logical move because to the west were

the mountain ranges of "the gap," with limited

westward access. At that time the boundary between X Corps and

Eighth Army was on the west side of the reservoir with no need

for Marine units to be sent to Yudamni.

The

"ridiculous plan" (Ridgeway's hindsight) to send

the 1MarDiv west did not consider of the terrain nor the time of

year. This plan called for the movement of RCT 31 to the east

side of the reservoir to relieve the 5th Marines so they could

move west with the division. The 7th Infantry Division then

taking over the sector east of the reservoir – north to

the Yalu. As it was, the plan called for urgent relief of the

5th Marines east of the reservoir, executed with such haste that

all units of RCT 31 did not reach the Chosin area before the

Chinese attacked and closed the MSR.

On the

afternoon of 26 November the 2/5 Marines moved to Yudamni to

prepare for the attack the following morning, the date ordered

by X Corps, leaving Faith's 1/32 as the third infantry

battalion for the 5th Marines should they have been needed. On

the morning of 27 November the 2/5 Marines initiated the attack

west of Yudamni as the remainder of the 5th Marines began

withdrawing from positions east of the reservoir. The 2/5

Marines were stopped cold by the dug in and

well‐camouflaged Chinese, who by their presence announced

they were there in strength. Of interest and not mentioned in

the pamphlet was the original Chinese plan for attacks in the

Chosin area. They had been scheduled to attack on 25 November,

the same day the Chinese launched their attack against Eighth

Army. Since forces were not ready, the attack was postponed and

executed the night of 27 November. Those who believe the Chinese

planned to attack two marine regiments at Yudamni must work this

fact into "what if?" analysis, realizing had they

attacked as originally planned, they would have attacked one

marine regiment on each side of the reservoir. The Army RCT

planned for Chosin would still have been east of the Fusen

Reservoir. With the 5th Marines departing and RCT 31 arriving on

27 November, the Chinese commander had no time to make changes

in his plans. He attacked that night.

EAST OF CHOSIN

(p.45‐46) The

pamphlet's introduction to RCT 31 begins with the arrival

of Faith's 1/32 Infantry on 25 November. We note that

"a patrol of Taplett's battalion had almost reached

the northern end of the reservoir before brushing up against a

small party of Chinese," with no explanation. What type of

patrol was this, how far was the northern end of the reservoir

from the 3/5 positions; in other words, what does "brush

up" mean?

Of significance is the next

paragraph that states "With the relief of RCT 5 by

Faith's battalion, Marine operations east of the reservoir

would end." Did they actually believe the presence of 1/32

relieved them of the responsibility for the zone of operation

east of Chosin? Of course not, so why say it?

Although "Faith's command relationship to the 1st

Marine Division is not clear," we believe there was no

question at the time. Faith was in the tactical zone of RCT 5

with no way of getting operational or logistical support other

than from the Marines. And, had the Chinese attacked (as

planned), Faith's 1/32 would have fought with RCT

5.

We then come to the statement that Murray

"did caution Faith not to move farther north without orders

from the 7th Division," a statement often misused by

historians. This adds confusion to the next statement that

"once Murray departed, the only radio link between Faith

and the 1st MarDiv would be ... [Stamford's radio]"

when, in fact, the RCT commander and his units were about to

arrive as stated by BGen Hodes during his visit to Faith on 26

November. The caution not to move further north has been

confusing, some believing the intention was not to move into the

forward Marine battalion position. Some believe that Faith

occupied the northern 3/5 positions on his own. The use of

hearsay in describing a situation continues to confuse and

create a smoke screen, just as inferring that RCT 31 paid no

attention to the enemy threat when they saw the threat just as

Murray saw it, for he was their only source of information at

that time. Missing is an exchange between Murray and MacLean on

26‐27 November.

RCT 31 EAST

OF THE RESERVOIR

(p.48) "Faith, ignoring

Murray's caution, received MacLean's permission to

move his battalion forward the next morning to the position

vacated by Taplett's [3/5] battalion." Without an

explanation, the words "ignoring Murray's

caution" is once again difficult to understand since

Maclean [RCT 31] was ordering [OpO 25] 1/32 to occupy the

northern battalion position of RCT 5. The road east of the

reservoir was narrow and Faith's movement north would have

to wait for the southbound movement of RCT 5 (minus one

battalion) which would take most of the morning.

p.5253 Under a subheading "Chinese Order of

Battle" the reader learns that "Sung would make the

destruction of the 1st Marine Division ... his main

effort." Then we read that the "27th Army ... was

charged with attacking the two Marine Regiments at

Yudamni." This is not correct. However, it does serve to

reinforce Chosin hype that Yudamni was the primary objective of

the CCF. This does not address the enemy plan to drive south

through the Marines east of Chosin and cut off the Marines at

Yudamni. The author has elected to follow the Chosin

"story" of the past rather than explain the Chinese

commander's plan and the execution of that plan which has

been known to historians long before the publication of this

pamphlet.

The I&R Platoon didn't

"roar out of the compound" because "several

hundred Chinese had been sighted." The platoon by OpO 25

was given the mission of establishing a screen east of the

Inlet, a direction of major concern to MacLean since the RCT

left the Fusen area.

Once again we read that

the RCT units were "stretched out on the road for 10 miles

in seven different positions." If a map with unit

dispositons had been provided the reader would have learned that

the combat battalions were disposed within supporting distance

of each other. The two forward battalions, 1/32 and 3/31,

occupied the two forward battalion positions occupied by RCT 5

just a few hours before. Ray Embree's battalion CP occupied

the location of Murray's RCT 5 CP.

Faith

did not received orders "to attack the next morning."

He received OpO 25 in writing delivered personally by RCT 31

liaison officer Lt. Rolin Skilton, an order that stated the RCT

would attack "on order," which means be prepared to

attack when ordered to attack.

The attack

"east of the reservoir" was made by the 80th CCF

Division reinforced by a regiment of the 81st CCF Division. On

the second day the CCF commander committed the remainder of 81st

Division and held the 94th Division in reserve for his main

effort down the east side of the reservoir.

ALMOND VISITS FAITH

p.58‐59

"[MacLean] knew little about what had happened south of the

inlet." This is not accurate, see Breakout by Hugh Robbins,

CJ02.28.04. "Col. MacLean came back from the 1/32 CP about

dawn and reported things were pretty much under control and all

units of the battalion were holding. The 57FA reported that A

Battery was being overrun... . Their CP was under considerable

fire and partially surrounded.... the 3/31 reported its command

post was under heavy fire and close range attack. In quick

succession reports came in that Reilly and Embree had both

become casualties, though not killed." As we can see, Col.

MacLean knew far more about the Inlet battle than had been

reported in the past.

"Stopping to see

MacLean, Almond advised him that the previously planned attack

would be resumed once the 2/31 joined the regiment. This

battalion and Battery C of the 57FA were marooned far south on

the clogged MSR."

Battery C/57FA had

been detached from RCT 31 and remained in the Puckchong area,

while A/31FA (155mm) had been attached to 57FA and never did

make it to the Chosin area. See RCT 31 OpO 25.

Noted are the photographs of the Inlet area that are

credited to (courtesy of) Norman Strickbine. These same photos

can also be found in Appleman's two books credited to

either Embree or Miller. The original source is a set of 18

photos by Ivan Long of Hq/31 who had been with MacLean's

forward CP. It is believed that many copies of this set were

made and found their way into the hands of wounded personnel in

Japan. Sgt. Strickbine was a photographer with Hq 13th Engineer

Battalion.

MACLEAN'S

DISAPPEARANCE

P.65 "His comrades buried

him [MacLean] by the side of the road." A search for more

detail on this subject takes one eventually to a footnote in

Appleman's East of Chosin, p.147, which then takes one to

p.365 where we find n.35 "I recall reading a newspaper

interview with the soldier that told of Col. MacLean's

death and burial. The soldier interviewed was probably one of

the thousands turned over to American Authorities during the

armistice prisoner exchange in 1953. I made a clipping of the

article and put it with other Korean War notes. Now, more than

30 years later, I cannot find the clipping and provide the

citation. But I am so certain of the facts recounted that I have

no hesitation in including them in this narrative." This

should excite historians to ask more questions. Who was the

source, where did the burial take place, who gave them the tools

to dig a grave in the frozen ground, and finally, was there ever

a follow‐up with a second source to verify the story?

Those who have interviewed American prisoners who made those

long night marches to the first prison camp at Kanggye find it

difficult to accept the story.

END

NOTES

Due to the length of the pamphlet being

discussed, we will continue our review in the next issue of the

Changjin Journal.

END CJ

10.10.04

|

|