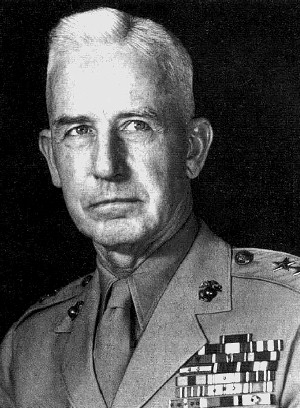

Maj. Gen. O.P. Smith

CHANGJIN JOURNAL 01.31.06

The Changjin

Journal is designed to disseminate and solicit information on the Chosin campaign. Comments and brief

essays are invited. Subject matter will be limited to history of the Chosin campaign, as well as past or

present interpretation of that history. See End Notes for distribution and other notices.

Colonel

George A. Rasula, USA‐Ret., Chosin Historian

Byron Sims, Contributing

Editor

IN THIS ISSUE we begin our 2006 series of the Changjin Journal by approaching the

Chosin Campaign from the viewpoint of Major General O.P. Smith, commander of the 1st Marine Division. We

will use his Aide‐Memoire as a basis, providing the reader with copies of his memoire within which

we will provide comments from various sources that relate to the topic at hand. This issue begins with the

battle of Sudong, an engagement by Marine RCT‐7 with the 124th CCF Division. Sections (…) and page numbers […] will be

included for reference purposes.

Bold typeface will be used for

emphasis, with editor's comments in [brackets]. Readers are reminded that these documents were

not written at the time of the action, but probably finalized by the general long after he left Korea. His

primary sources were unit reports and briefings by commanders, and his own personal diary. However, they

do reflect his view of what happened, as well as how he wished them to be remembered.

THE BATTLE OF SUDONG

This 1:50,000 scale map is from an original 1950 map carried by a member of

an artillery unit supporting RCT‐7 during it’s attack north to Sudong, labeling this sector

“Nightmare Alley.” Scale: grid lines are 1,000 meters apart; contour lines are 10 meters

apart, indicating very steep slopes on both sides of the road, the MSR north to the Funchilin Pass.

OPS

522‐537

(210) Destruction of the 124th CCF Division by

RCT‐7

In

implementation of X Corps OI‐13 of 25 October, 1MarDiv OpO 18‐50 of 28 October directed

RCT‐7 to relieve element of I ROK Corps along the Hamhung ‐ Chosin Reservoir road and to

advance rapidly to Objectives 1 (Koto‐ri) and 3 (Hagaru‐ri), prepared for further advance to

the northern border of Korea. RCT‐7 was directed to destroy all enemy in zone.

By 31 October,

RCT‐7 had completed its move to Hamhung and was assembled in the northern outskirts of Hamhung.

Plans were made by RCT‐7 to move to the rear of the 26th ROK Regiment in the vicinity of

Majon‐dong (22 miles north of Hamhung) on 2 November and to relieve that Regiment in place.

Arrangements were made for OY cover of the flanks commencing at 0800, 2 November, and for fighter cover at

1000 that date.

On 1 November, RCT‐7 moved approximately 20 miles up the road toward

Majon‐dong and took up defensive positions in rear of the 26th ROK Regiment in the Majon‐dong area. No enemy

contact was made during the approach march. Plans were made to relieve the 26th ROK Regiment on 2 November.

CONCERN ON 1 NOVEMBER

At 1400, 1

November, General Shepherd and I flew by helicopter to Hamhung to pay a visit to Colonel Litzenberg. His

Regiment had started to move toward Majon‐dong but Colonel Litzenberg was still in his CP in the

northern outskirts of Hamhung.

Litzenberg was rightly concerned over the situation. By this time word had trickled in of the reverses

suffered by the 8th Army in the west. The 1st Cavalry Division had incurred serious losses at the hands

of the Chinese and at least one ROK division had been rendered ineffective by Chinese

action. The 26th ROK Regiment, which was being relieved by

RCT‐7 the following day, had already engaged the 124th CCF Division, had captured 16 prisoners, and

had identified two of the regiments of the 124th. The impression Litzenberg had was that the 26th ROK

Regiment was very happy to be relieved. Litzenberg's orders required him to occupy Koto‐ri as

a first objective. Koto‐ri was 23 road miles north of Majon‐dong. The right flank

of the 8th Army was approximately 60 air miles southwest of

Majon‐dong and the 8th

Army was not advancing. As

RCT‐7 advanced to the north the distance to the 8th Army would become greater. There was nothing on this open

flank except the Division Recon Company, later relieved by the 1/5 Marines, operating on the road from

Chigyong northwest to Huksu‐ri. Yet there was no relaxation of the pressure by the Corps to make

rapid progress in the direction of the Chosin Reservoir. Under these circumstances, there was no

alternative except to continue forward in the hope that the 8th Army situation would right itself and that we would

…

[p.324 is missing]

[325] … reported an estimated enemy force of two battalions on its

left flank. From 0145, 3 November, throughout the night, the 2/7, the Anti Tank Company, the 4.2 Mortar

Company, and B1/7 came under heavy enemy coordinated attacks.

3 NOVEMBER

Two enemy tanks

were reported headed south on the Sudong road at 0438, 3 November. At 0520, one of the tanks had been

destroyed and was observed burning while the other turned around and returned to the village of Sudong. At

0636, the 1/7 was still under enemy attack, which lessened to moderate intensity during the day. Small

arms, automatic weapons, and sporadic mortar fire harassed RCT‐7 during its advance. During the

morning, the enemy succeeded in infiltrating sufficient troops to block the road at a bridge south of

Sudong. Covering the road with fire, the enemy effectively cut the MSR between the 1/7 and 2/7 and the

remainder of the RCT. The Division Recon Company was sent around the enemy's flank to dislodge him

from his well selected positions and air strikes were directed on him which forced him to abandon his

positions. The cutting of the MSR necessitated air drops of supplies to the 1/7 and E2/7. They were

successfully made. During the day the enemy suffered heavy losses.

RCT‐7

reported that the Sudong area was generally quiet during the night of 3 ‐ 4 November, although the

enemy attempted to infiltrate the right flank of the 3/7 at 2100, 3 November. The attack was repulsed by

machine‐gun and 60mm mortar fire and the enemy was forced to withdraw. Two light contacts were made

on the 1/7 left flank which were repulsed by fire. Also several rounds of light mortar fire fell in the

2/7 positions during the night.

4 NOVEMBER

At first light, 4

November, the 1/7 began patrolling the road to Sudong, and, at 0800, the Division Recon Company moved out

to patrol to the front and lead the advance of RCT‐7. RCT‐7 moved out at 1000 with 1/7 and

3/7 in column and the 2/7 in reserve. Patrols reported that the enemy was withdrawing northward, which was

confirmed by air. The air spotted four trucks and five tanks moving northward. Moderate resistance was

encountered during the advance. Four enemy tanks were surprised by the Recon Company just south of

Chinhung‐ni (6000 yards northwest of Sudong), and were destroyed by the 1/7. Two were accounted for

by 3.5 rockets, one by 75 recoilless gun, and one by aerial rocket. Positions and CPs were consolidated

for the night at the south end of the valley at Chinhung‐ni. The Recon company and 1/7 patrols

encountered heavy enemy resistance just north of Chinhung‐ni and broke contact just prior to

darkness. One enemy tank approached the 1/7 lines during the night but withdrew without coming within

range of anti‐tank guns. During the advance to date it was estimated that RCT‐7 had killed

790 Chinese.

5 NOVEMBER

At 0400 on 5

November, the 1/7 positions were attacked by an estimated 30 enemy. No other attempt were made during the

night to infiltrate our lines. At 0900, 5 November, the attack of RCT‐7 jumped off with the 3/7

passing through the 1/7 to make the attack and the 2/7 following at 500 to 1000 yards. The 1/7 , when

passed through, was to hold positions to protect the flanks of the remainder of the regimental column. The

advance came up against well defended enemy position on the high ground north of Chinhung‐ni. The

enemy's determined stand considerably slowed up the advance and gains of only 1000 yards were made

during the afternoon. Extensive use was made of air strikes and artillery to neutralize the enemy's

positions, inflicting heavy casualties on the Chinese forces. The enemy retaliated with heavy mortar,

small arms, and automatic weapons fire, with an occasional artillery round. At 1100 on this date [5 Nov] I

flew by helicopter to Litzenberg's CP near Chinhung‐ni and was a witness to the intensity of

the air and artillery fires being put down on the enemy's positions.

During the night of

5‐6 November, approximately 30 rounds of mortar fire fell in the Regimental area, bugles were heard

forward of the front lines, and there was evidence of increasing enemy activity in front of the 3/7.

Artillery fires were delivered on suspected concentrations of enemy troops. No enemy attacks materialized

during the night.

6 NOVEMBER

For 6 November, RCT‐7 planned to attack with the 3/7 in the assault. The 2/7 was to consolidate positions held during the night for the protection of dumps and the artillery, and the 1/7 was to consolidate the positions it held on the night of 5 November. The attack was launched at 0800, 6 November, but was slowed by heavy small arms, automatic weapons, and mortar fire, from well entrenched enemy positions on the high ground north of Chinhung‐ni. At approximately 1330 the 3/7 came under an enemy counterattack on its left flank by an estimated company of enemy attacking from the direction of Hill 987 (3000 yards northwest of Chinhung‐ni). This attack was repulsed. At 1610, the battalion [3/7] received another counterattack, this time from the right flank against H3/7. By 1730, H Company was engaged in a very close range fire fight well up on the slopes of the objective. Darkness had set in and the enemy began a grenade attack which was very effective. At 1800, with ammunition low and with many casualties, H Company requested permission to retrieve its dead and wounded and withdraw to the battalion [3/7] perimeter. Permission was granted and the withdrawal was completed by 2000. Heavy artillery concentrations were put down on the area from which the company had withdrawn.

During the day of 6

November, the Division Recon Company was ordered by RCT‐7 to reconnoiter from Major‐dong to

the vicinity of Sinp'ung‐ni (about 7 miles northwest of Majon‐dong). Questioning of

civilians indicated that 200 to 400 CCF troops occupied the town during the night of 5

November and were still in the vicinity. Effective at 1600, 6 November, the Recon Company was detached

from RCT‐7 and was ordered by the Division to continue recon to the west of Majon‐dong to

the limit of its capabilities.

In accordance with regimental orders issued at 2000, 6 November,

at 0900, 7 November, the 3/7 dispatched patrols in the direction of Hill 891 (3500 yards east of north of

Chinhung‐ni) and the 1/7 patrolled along the southeast slopes of Hills 987 and 1225 (3000 yards

northwest of Chinhung‐ni). No enemy contacts were made by the patrols. The 3/7 moved out and

occupied the high ground to the front covering Chinhung‐ni. Numerous enemy dead were found and

there was evidence that many had been buried.

7 NOVEMBER

Air reported during

the day of 7 November that two self‐propelled guns had been destroyed north of RCT‐7's

positions and three enemy trucks west of its positions. Enemy troops were spotted in the vicinity of

Yudam‐ni (35 miles

northwest of Chinhung‐ni) which was struck by air. General Craig [assistant division commander]

visited the CP of RCT‐7 during the day.

In

RCT‐7's action against the 124th CCF Division from 2 to 7 November, reports indicated that

about 1500 of the enemy had been killed, 62 prisoners were captured and all regiments of the 124th were

identified. POW interrogation indicated that losses were heavier than reported by RCT‐7. These

interrogations revealed that losses were particularly heavy from artillery fire and that the combination

of infantry, artillery, and air action had so decimated the division that not more than 3000 of the

original 12,500 [8,500] were left as a group. The combat effectiveness of this division was manifestly

destroyed. It was several months before it appeared on the front again. [General Smith completed this

Aide‐Memoire after he left Korea.]

CASUALTIES

The casualties of

RCT‐7 for the period 2 ‐ 7 November amounted to 52 killed and 264 wounded.

In its advance

northward from Majon‐dong, beginning on 2 November, RCT‐7 employed sound and proven tactics

suited to the situation. It was operating in enemy territory beyond supporting distance of other friendly

units, a condition characteristic of operations in northeastern Korea, and had to be prepared to protect

itself to the front, flanks and rear at all times. It is an accepted principle that in advancing along a

terrain corridor the shoulders of the corridor must be occupied, or otherwise denied the enemy, before

movement can safely be made along the corridor. Practically all movement in Korea was along corridors.

Roads followed valleys flanked by mountainous terrain or wound through mountainous draws. Previously in

the Korean action, North Korean forces had been quick to take advantage of any failure of forces to get on

the shoulders of corridors before attempting to advance along the road through the corridor.

HISTORICAL COMPARISON

RCT‐7's solution of the problem was similar in some respects to the system evolved by the French in the Riff Campaign in North Africa in 1925. For movement across country through enemy territory, against an enemy who infiltrated and attacked from any direction, the French developed a mobile column formation consisting of a brigade of four infantry battalions with supporting artillery, service troops and trains. The column was self‐sustaining for long periods of time. It moved in a diamond formation, with mounted partisans screening the movement, and with the artillery, service units and trains in the center of the diamond formation. These mobile columns proved to be very successful.

[The foregoing is

related to the 1MarDiv plan for the breakout from Hagaru‐ri to Koto‐ri on 6 December, an

action described years later by Lt. General Al Bowser (Division G‐3 at Chosin), saying they had

planned that operation as a wedge, in effect a diamond formation with the trains protected by units on the

flank. The problem faced in that action was the lack of designated objectives and phase lines to control

the battle; a fault Bowser acknowledged. Smith's comparison of Africa with the terrain in the Sudong

gorge was influenced by his training at the French Ecole de Guerre (1934).]

Colonel Litzenberg

had only three infantry battalions and was operating in mountainous terrain, not in fairly open country

such as found in North Africa. The Partisans were replaced by patrols. Yet the formation and tactics used

by RCT‐7 accomplished the same purpose as the mobile column. The tactics employed by RCT‐7

were generally as follows: One battalion moved out in assault astride the road. Companies of the battalion

were assigned successive objectives which consisted of terrain features commanding the road and within

effective small arms or machine gun range of it. Both flanks of the RCT were covered by companies of a

second battalion operating out to a maximum of about 1000 yards from the road. The third battalion moved

in the rear, covering the flanks and rear. Artillery, service units, and trains were inside of this

formation. The advance was conducted by bounds. The assault battalion moved out a distance of

approximately 2000 yards; then the remainder of the RCT closed up, trains and service troops moving along

the road and the artillery displacing to advanced supporting positions. At the conclusion of the

day’s advance, the formation was closed into a perimeter defense adjusted to the terrain in the

area. The foregoing formation might be varied somewhat, with the assault battalion moving forward and

occupying critical terrain to cover the advance of the remainder of the RCT on the following day. In this

case the assault battalion established a battalion perimeter or company perimeters at night and the

remainder, in view of night infiltration tactics of the enemy and his use of mass attacks, was considered

of more importance than dominating terrain. The perimeter was not stretched to the point of weakness to

occupy commanding terrain features. In defense positions during daylight hours, patrols were dispatched to

the front, flanks, and rear to determine the presence of the enemy and give adequate warning.

Coupled with

appropriate tactical formation, RCT‐7 combined the power and feasibility of artillery fire and the

destructive effect of air attacks to produce a decisive effect upon the enemy. The tactics and techniques

employed by RCT‐7 remained valid throughout the Korean War.

[The negative side to the

tactics and techniques explained by General Smith is the tendency to withdraw into tight unit perimeters

for the night and leave the unoccupied terrain available to the enemy. The absence of intensive night

reconnaissance played an important role in allowing the Chinese to employ their tactics of delaying

until they were prepared to strike in force. Sudong was but a delaying action, part of the larger plan

to build up their forces to strike at the right place at the right time.]

(211) The

Chinese Enemy at Sudong and Chinhung‐ni

In its advance from Majon‐dong to

Chinhung‐ni, RCT‐7 was opposed by the 124th CCF Division, of the 42d Army (Corps), of the 13th Army

Group, of the 4th Field Army.

NIGHTMARE ALLEY

The 124th Division was one of the three CCF divisions of the 42d Army which crossed the Yalu River about 20 October. The 124th moved southward from the Chosin Reservoir into the Sudong area about 30 October. The entire division closed into that area two or three days later, taking over the defense of that route from the North Korean units what had been delaying northward. Composed of the 370, 371 and 272nd regiments, this divison had an overall strength of from 10.000 to 12,000. [An estimate of strength based on enemy documents is more like 8,500.] Each regiment had three rifle battalions, while each battalion as made up of three rifle companies and a heavy machine gun and mortar company. In addition to headquarters and service units, the division had an organic artillery battalion which was equipped with 120mm mortars and U.S. 105mm howitzers, both of which they used effectively against our CPs and installations.

70% of the

personnel of the 124th Division, according to prisoners, were former members of the Chinese Nationalist

Army who had been captured by the Communists during the Chinese Civil War and subsequently inducted into

Communist units. It is significant that former members of the CNA were never found in positions of

responsibility or leadership, such jobs always being accomplished by trustworthy Communists. [Since

resupply had to come all the way from China, this heavy part of the logistics load had to have been

rationed. When ammunition ran out and resupply was no longer possible, the division had but one

recourse‐‐withdraw. That they did.]

The organization

and composition of the 124th Division followed the conventional CCF lines. One prisoner out of the division artillery

battalion stated that his company, (2d Co.), consisted of 170 men, the company commander, an assistant

company commander, a political instructor and an assistant political instructor, four platoon leaders

(headquarters platoon and three artillery platoons), and three assistant platoon leaders. The headquarters

platoon was provided with two horses, one for the company commander and one for the communications

equipment, probably a radio. Two of the artillery platoons had 16 horses each and with two 105mm howitzers

each. The fourth platoon as a service or ammunition platoon with 20 horses for carrying ammunition. The

company had a total of 108 rounds of 105mm ammunition. The POW, also a former Nationalist, said that

during his two years in the Communist Army he had received practically no military training and stated

that political training was considered to be the most important of all. Each company had a political

instructor who lectured several hours daily on Communist doctrines. Since June 1950, the POW stated, much

emphasis during the lectures was given to talks on "American Imperialism". [Who fed the

horses?]

The mission of the

124th Division was to block the movement of the 7th Marines toward the Chosin Reservoir. [When first

sent to Sudong the mission was to delay the movement of the 26th ROK Regiment leading the movement of the American

Imperialists in their attack toward China.] The failure of that division to carry out its

mission was quick and decisive. [It was not a failure because they accomplished their mission of

delaying the move north by the lead units of the 1MarDiv.] Our attacks began at noon, 2 November and

by nightfall of 6 November the remnants of a one full strength division and had begun their hasty retreat

northward toward Hagaru‐ri. The 370th and 371st Regiments had successively been defeated in fierce

ground action and late on the 6th the 372nd Regiment, moving up from its reserve position, was virtually

annihilated by a heavy artillery barrage which caught it moving up into position on a hill which had

previously been held but vacated by our troops. The enemy withdrew out of contact that same night. To

cover that withdrawal, elements of the 126th Division, which had seen only patrol clashes around the Fusen

Reservoir, moved into the vicinity of Koto‐ri along the east side of the MSR. The 126th was never

engaged, the withdrawal of all CCF units having been effected by the time the 7th Marines reached the

Koto‐ri and Hagaru‐ri areas. [Success can only be supported by aggressive pursuit. That

did not happen.]

The only appearance of armor in the support or Chinese infantry appeared during this fighting when the 344th Hamhung (North Korean) Tank Troops (Regiment) committed a group of five T‐34 North Korean‐manned tanks. These tanks, the remnants of the 344th, gave little resistance to our advance as they were knocked out by 3.5 rockets, aerial rockets and 75mm recoilless gun fire. [Tanks were useless in that narrow gorge from Sudong northward, except for psychological effect against those who had no knowledge of armor capabilities and limitations.]

POWs said that

heaviest losses to the 124th Division had been inflicted by artillery fire, and that a combination of

infantry, artillery and air action had struck the division so thoroughly that no more than 3,000 of the

original 12,500 [8,500] effectives were left as a group.

[p.537]

END NOTES

The next section is a brief outline of the provisions of 1MarDiv OpOrder 19‐50 of 5 November, followed by (213) Reconnaissance and Occupation of the Sinhung Valley by RCT‐5 which we will include in the next issue of the Changjin Journal.

Reference: Aide‐Memoire—Korea 1950‐51. Notes by Lt. General O.P. Smith on the operations of the 1st Marine Division during the first nine months of the Korean War.

End CJ 01.31.06

|

For past issues of The Changjin Journal go to the Changjin Journal Table of Contents The new e‐mail address for The Changjin Journal is < grasula@nymas.org >

|