Map 8‐6 The Chosin Chronology

Click on the map for a full‐screen image; use your

Back button to return to this text.

Withdrawal of

1/32 to the Inlet. Note the dotted line crossing the Inlet; this is the area where Col.

MacLean crossed the ice and was wounded and captured by the Chinese.

Columns of troops formed on

each side of the vehicles and moved to the front. All preparations had been completed by

about 0430 hours and the column began to crawl forward. Many vehicles that could not be

started had to be left behind, but none of the wounded were without transport. That was

the important task at the moment. It was strangely quiet behind as we moved down the

road towards the 3d Battalion. Our rear guard reported later the Chinese seemed content

to allow us to withdraw without any extreme effort on their part to follow closely.

Actually this must have been true. I believe the enemy spent time looting the area we

had evacuated before organizing for an effective pursuit. Their need for supplies was as

acute as ours. About daylight we had progressed to the vicinity of the former regimental

CP site before the column was halted.

I walked forward along the

vehicles and soon came abreast of Col. MacLean's jeep with only his driver. A few

yards beyond was a bend in the road which shut out the view. I was informed the colonel

was on the road making a reconnaissance of a reported roadblock that had caused the

halt. A small straggling group came from the direction of the bend and told us a company

of our troops was encircling the roadblock. No one seemed to know exactly where the

colonel was, but I suspected at the time he was with the company going after the

roadblock. That suspicion was proved wrong as I shall relate later; he was ahead of the

company! As we waited for the go‐ahead signal someone came down the line of

vehicles yelling that vehicles were to get off the road and disperse in an open area on

our left. We promptly drove into the area and dismounted. When some 60 vehicles were so

placed, personnel were instructed to take up a defensive position in case the Chinese

caught up with us again or tried to come in on our left flank before we could resume our

road march. We waited for what seemed hours and were getting more concerned by the

minute, as we knew the Chinese behind us would not fool around all day going through the

abandoned area we had occupied, and would soon be hot‐footing down the road

toward us.

CAUGHT BY SURPRISE

Soon a small squad of Chinese

did just that and were as surprised as we were. They had come trotting around a bend in

the road not 20 feet from the nearest vehicle. In a moment of firing was going on all

directions. The enemy must have thought they had run into an ambush and took to their

heels. Lt. McNally and I had taken cover beside a mud house and for a few minutes I

thought that a sizable force had begun an attack on our position. Then someone began and

others repeated the call to cease fire, and all became quiet. Order was

restored.

I made my way up the road again toward the location of the

roadblock and once more came upon the colonel's jeep. This time his bodyguard and

radio operator, who rarely ever left the colonel's side, were looking concerned and

talking excitedly. I was told the colonel had not gone with the enveloping company

toward the flank of the roadblock, but had gone boldly down the road directly toward the

obstacle and had not returned. It might be explained at this time that about a mile

separated our halted motor column and foot elements of the 1st Battalion from the site

of the roadblock; and just in front of the roadblock was a

hundred‐foot‐long concrete bridge over the frozen inlet of the reservoir.

A scant 200 yards beyond the bridge was the encircled 3d Battalion, our goal. I moved

cautiously to the bend where I had view of the bridge. With field glasses I could make

out troops along the bridge supports firing at some target on the opposite side of the

bridge.

About this time Lt. Col. Faith came striding up with the news

that his company had cleared the roadblock. The men I observed were our own troops

holding the bridge and would cover our dash over and to the safety of the 3d Battalion

area. That was the plan. Start up the vehicles again, get them on the road and send them

one at a time over the bridge which was still under fire from the surrounding hills,

though it was held by our troops. With the Chinese at our backs there was no hesitation

in anyone's mind. Drivers floor‐boarded their accelerators as we ran the

gauntlet. Although some of the vehicles got hit, no casualties were reported. We

regrouped on the far side of the bridge. I felt quite lucky as we pulled to the halt,

and after inspecting our jeep found not a single hole.

Leaving the

jeep parked in the new area I set out for the 3d Battalion CP where I found Lt. Col.

Reilly propped on a stretcher with a bullet hole through his leg and grenade splinters

lightly sprinkled in his arms and shoulder. He was in good spirits and chatted with me

about the situation in general. Lt. Col. Faith came in at this time and went into

immediate conference with Reilly as they laid plans to consolidate the two infantry

battalions and the field artillery battalion.

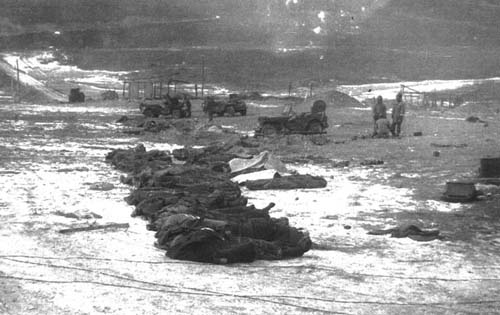

Dead Chinese soldiers. "Dead Chinese

soldiers shot by Retherford and Donovan inside the perimeter near the 3/31 command

post." ‐ MSG Wm. Donovan

I cornered Capt.

[Robert] McClay, 3d Battalion adjutant, and got from him the story of the hammering and

slashing they had taken from the enemy the night before. One had only to look about as

he told the story to confirm everything he said. Dead and wounded GIs lay in and around

the Korean mud house that served as a CP, and just a few yards beyond I counted 20 dead

Chinese in their now familiar quilted jackets and tennis shoes. In fact, they were

strewn throughout the area giving evidence of their penetration into the foxholes of the

beleaguered battalion and its command post. How the Chinese were finally pushed back as

dawn came, and how those soldiers of the 3d Battalion kept firing until the Chinese

retired to the protection of the hills, will be a tribute to that unit forever. Capt.

McClay said simply there was nothing else to do and no place to go, so they just stayed

in their holes and shot Chinese until the fanatical enemy had enough and

withdrew.

TWO OFFICERS WERE DYING

Casualties in the

battalion ran high, especially among the officers. Dropping by another mud hut that

served as a hospital, I found Capt. [Melville E.] Adams, S‐4 of the 3d Battalion,

dying of wounds as was Lt. [Paul N.] Dill [M3/31], a fine officer. Capt. Wamble of the

31st Medical Company was also in a bad way with bullet wounds through his lungs; he

could hardly speak above a whisper as I chatted with him briefly. We had been good

friends back in Japan and I was shocked to see Henry in such a state. He was pessimistic

about our chances of getting out and showed me his .45 pistol which he dragged out from

under the blanket. He told me that he would shoot himself rather than let the Chinese

capture him. That was the last time I saw Henry, and though he was placed on a truck

when we finally left the area, he was never reported to have made it to

Hagaru‐ri. How he fared we will probably never know.

When I

returned to the area where Lt. Col. Faith had established his CP, I learned that Col.

MacLean had been captured a short while before. It was reported he had mistaken a group

of Chinese for GIs, and upon running towards the group he was fired on and wounded. He

struggled to his feet, the report went on, and again started toward the group and was

shot down once more. This time men in the group who were identified as Chinese dragged

the colonel off with them as they withdrew. This action had taken place in the vicinity

of the roadblock. The colonel was never seen again and is listed as

missing.

As the afternoon [29 November] wore on we set about digging

foxholes and establishing the 1st Battalion into the defenses of the other units already

there [3/31 and 57FA]. I took over Col. MacLean's jeep and crew. Together we dug

into the side of a small embankment, with an overhead cover of logs. This would give us

partial protection from any direct hits by mortar shells or artillery bursts overhead.

Leaving the men to lay out sleeping bags inside our new home, I went to search for Lt.

Col. Faith and his executive officer. He had taken over after viewing the condition of

the other two battalion commanders. I was appointed the "task force

S‐4." I set about organizing the collection of supplies in the area so that

equal distribution could be made. About 1530 hours my supplies were built up by an

airdrop. Two C‐119 Flying Boxcars were overhead and after two trial passes

spouted their cargo of colored parachutes with much‐needed ammunition and

rations. One of the chutes failed to open and the heavy cargo came down like a stone.

Before we could get off a warning it hit among a group of ROK soldiers about 20 feet

from me, killing one of them immediately. After that, when an airdrop was pending, loud

yells of warning kept everyone alert for falling cargo.

'COPTERS TAKE OUT

WOUNDED

About an hour after the airdrop two helicopters in the vicinity

were contacted and directed to land within our perimeter. They evacuated a few of

the more seriously wounded to Hagaru‐ri that afternoon, but darkness

prevented them from making but two trips out and back. The next day when our forward

air controller (FAC) contacted them, we learned that other units in similar trouble

had priority over us.

"Inside the Inlet perimeter. In center

of the picture are three helicopters that landed to pick up wounded, landing about

400 yards west of the bridge/causeway. To the left is a 40mm M‐19 track of

D/15th AAA. In the center foreground is mortar position of L3/31. Man in the photo

by the hole is squad leader SGT Luther Crump." ‐ MSG Wm.

Donovan

With a

strengthened defense we stood our watches that night and set ourselves for attacks

we knew would come about midnight. About 2300 hours our artillery began to fire and

the cough of our mortars started up. Next the machine guns on the perimeter took up

the chatter and were joined by the firing of our M‐1 rifles. The crack of

rifle and machine gun bullets coming in overhead told us the Chinese were coming

from the hills to the south and into the defense of the newly arrived 1st Battalion.

The Chinese wanted to try them out. The reception was too hot and in about an hour

the Chinese gave up trying. With a lot of bugle blowing they returned to the hills.

All became quiet again. And so it went for the rest of the night and early morning

with only occasional firing of our mortars on suspected enemy positions and

infrequent fire from our outposts. This was surprising as we had expected the enemy

to double his efforts that night.

Daylight came slowly on 30

November with ground fog persisting until after 0800 hours. About 1000 hours the

skies cleared and another air‐ drop came in, bringing more precious supplies.

We were still short of ammunition and appealed over the radio to the aircraft for

more. Gen. [David] Barr, our division commander, paid us a surprise visit that

morning and promised to do all he could to get us better supplied by air. He was

quite worried, as I had never seen him before, and for good cause. His information

was that a tank‐led task force had been trying for two days to reach our

surrounded garrison and had been severely mauled and turned back. We then realized

the full gravity of our situation. Lt. Col. Faith decided that he would prepare to

fight our way out of the trap, but wanted to get better supplied with ammunition

before making the effort.

That night we went into our holes and

waited for the Chinese. They didn't disappoint us. About 2000 hours they began

to lob 120mm mortars and light artillery into our perimeter. We could hear the dull

boom of guns followed by the swishing of projectiles singing through the air all

about our emplacements. Our 105mm artillery began retaliation but their fire went

unobserved and probably did the enemy batteries little damage. The Chinese fire was

in preparation for an assault by foot troops and kept up for about 45 minutes.

Luckily none landed close to our hole to cause more than an occasional shower of

dirt. We could hear the smack of steel when fragments hit an exposed vehicle, and

that was often. Some of the men weren't as lucky, as I could hear calls for a

medic from several directions.

"Bodies of soldiers from 3/31 killed

inside the perimeter. Most are from Company L and Battalion Headquarters Company.

Burial was not possible because of frozen ground." ‐ MSG Wm.

Donovan

MORTAR FIRE

WOUNDS MEDICS

The aid station the 3d Battalion had set up that afternoon

was directly behind our hole and had the misfortune of receiving two near hits by

incoming mortars which wounded some of the medics and those already wounded. The

heavy stuff lifted and the enemy gunners began to step up their pace. The Chinese

who had been creeping nearer and nearer all this time began to pour in with their

burp guns and rifle fire. The snow outside our hole spurted every now and then as a

slug plowed into the dirt. The air over my

head was alive with the buzz and

crack of incoming bullets. We could hear the yells of our own troops mingled with

those of the Chinese as the outer defenses clashed.

Our troops

withheld fire until the enemy was well within range, then cut loose with everything

they had. Attacks were being made on all sides. There was business for

everybody.

All night waves of Chinese soldiers attacked our lines

and were held off. Our machine guns were taking a terrible toll and our artillery,

having lowered their guns to fire point‐blank at the screaming hordes, hacked

huge holes in their ranks. Very few Chinese infiltrated past the outer perimeter and

those who did were killed before they could do much damage.

There

was one sniper who proved troublesome all during the early morning hours by firing

past our foxhole into the dirt beyond. Evidently he was causing others trouble also,

as a patrol was formed and came by our hole with the mission of locating and

eliminating the sniper. He could not have been more than 20 yards behind us but was

so well hidden in the murky darkness that they could not find him. He kept up his

firing off and on until well after daylight, then his fire suddenly ceased. Someone

got him or he took off. Anyway, it became safer to come out of our holes. Although

the Chinese withdrew from the edge of the perimeter, they still kept up a harassing

fire and casualties among our men continued. The morning of 1 December at about 0900

hours I crawled out to our jeep and dug up a can of frozen beans. Others found the

same fare and we went back to our hole and built a small fire but it wasn't

enough. We ate the rations anyway. Nothing so delicious as ice crystals in your

beans! That was all we had so there wasn't much bitching about the chow. No one

volunteered to scout for more wood to build another fire so the topic of food came

to a rapid close.

"Inside the perimeter. A small Chinese

attack was moving in from the hill to the right and rear of the bridge. The

M‐16 Quad‐50 machine guns are firing into the attacking Chinese."

MSG Wm. Donovan

CLOUDS LIFT,

CORSAIRS ATTACK

The low‐hanging clouds still persisted and we began

to sweat for fear that our daily fighter cover and expected airdrop would not come.

Our position on the ground was obscured by the clouds. About 1100 hours, however,

the sun broke through and our fighters came in to begin one of the prettiest shows I

have ever seen. They dived and dived again, covering the surrounding hills with

deadly rocket and machine gun fire. They dropped oblong containers of napalm that

sent up terrible pillars of flame. The Chinese dreaded napalm and cleared out when

it hit nearby. Lt. Col Faith came over to our hole and in a few quick sentences told

me the time had come to get out of there. He told me we must get the trucks warmed

up and the wounded loaded. At last we were going to try to break out of the ring of

Chinese. Waiting for airdrops was futile. We set about rounding up drivers and

getting the troops organized for the fight. It was within 10 minutes of my talk with

Lt. Col. Faith when I was taken out of the play.

I was making my

way to the 57th FA Battalion CP when an explosion knocked me sideways and down to

the ground. Stunned for a moment, I did not realize that a mortar round had landed

no more than three feet from me and shrapnel had hit me in the arm and leg.

Lt. McNally also became a casualty from the same burst. I looked at

my

carbine which had been blown from my hand and discovered it was useless.

The force of the explosion or some fragments had exploded several rounds in the clip

and the slide mechanism would not work. Sgt. [John] Lynch, my sergeant major,

reached me in a couple of minutes and helped me to a slit trench nearby. He rolled

up my pants, bandaged the gash in my leg and bound my arm. It wasn't bad as I

could hobble around. Lynch led me to a truck and put me aboard, telling me to stay

put. Other wounded were placed on the truck as preparations to leave were stepped

up. I lay face down in the left front of the truck bed and watched what was going on

through the slatted sides of the vehicle. Artillery gunners were dropping

phosphorous grenades down the muzzles of their guns. Jeep drivers were jabbing

bayonets into the tires of their abandoned vehicles and setting fire to them.

Remaining records and documents that could not be risked to capture were set afire

and supplies were soaked in gasoline and burned. The Chinese were well alerted to

our plans and had begun to throw in more mortar fire and became bolder with their

rifle fire. At last our trucks were loaded and our troops deployed beside the truck

column. At a signal we moved out. Marine and Navy aircraft dove into the wall of

enemy ahead and blasted with all they had. Ahead of our truck was a tracked vehicle

mounting a 40mm gun, but short on ammunition. Also ahead of our truck was a jeep

with a .30 caliber machine gun mounted on the front. This was our spearhead. Our

troops on either side of the road moved forward but were dropping from the withering

fire laid down by the Chinese as we moved forward.

NAPALM

SPLASHES OUR RANKS

Then came one of the most horrible sights I ever hope to

witness. A Marine Corsair diving toward the enemy line just ahead of our troops

dropped a tank of napalm that slammed into our front line of advancing GIs. A wall

of flame and heat rushed out in all directions, enveloping about 15 of our soldiers

in its deadly blanket. The heat and flash caused me to duck momentarily. Looking

back up I could see the terrible sight of men ablaze from head to foot, staggering

back or rolling on the ground screaming for someone to help them. This, coupled with

the steady whack of enemy bullets into our ranks, stopped the advance. I am quite

sure I recognized the helpless and blazing figure of Sgt. Dave Smith, my assistant

sergeant major and one of the finest men I have every known. He wasn't more

than 10 yards off the side of the road and I was powerless to do anything for him. I

had to turn my head. Officers and NCOs, through superhuman effort, rallied their men

and soon our line of GIs began to move forward again, filling the blackened gap that

had been blasted open minutes earlier. Our truck began to move forward once more and

I breathed a prayer of thanks, the first of many prayers that day. At least we were

through the first ring of Chinese who had surrounded our group two days before. They

were still in the hills on our left and hidden in the brush along the road, laying

down a hail of lead into our troops and trucks.

"Last photo inside the perimeter.

Donovan had gone back to make sure all equipment in his mortar position had been

destroyed, setting this jeep on fire." ‐ MSG Wm. Donovan

My leg began

to throb and I had to keep shifting to keep a more severely wounded man from rolling

on me. He was unaware of the whole ruckus and kept trying to raise up, especially

when a bullet smacked into the truck. I quieted him the best I could by telling him

we were going to get out, although I had my doubts. The other wounded on the truck

just lay quietly and stared into nothing. Most of them had been wounded before that

day and were on litters. None of them able to walk at all. As we moved forward in

jerks and halts, a few frightened ROK soldiers tried to climb into the truck but

were pulled off by GIs beside our vehicle. From my peephole I could see dead Chinese

and American soldiers lying in little sprawling heaps on the side of the road, their

blood forming pools from which steam rose into the freezing air. I remember looking

at this and realizing the fight those Gis were making. Soldiers passing our truck

called out encouragement and grinned as they went forward to fight more Chinese or

fall themselves. The enemy was giving way now and our men sensed it, following them

more closely and with greater courage.

About three miles down the

road we came to a bridge which had been destroyed. Our motor column turned off the

road into a wide riverbed to bypass the obstacle. Great mounds of frozen earth

covered with a tough grass carpeted the riverbed. For about 100 yards we bounced and

crashed up and down over those hummocks with the wounded screaming in anguish as

they were jostled and slammed into one another. Luckily I still had on my steel

helmet and thus was able to protect my head, although I had a bruised head for days

afterward. We came to a final jolting crash and stopped. Our front wheels were down

through a crust of ice in a small creek and no amount of effort on the part of our

driver could move the truck forward or backward. To top it off the engine went dead

and the driver departed as enemy fire began to crackle around our stalled truck.

Other vehicles began to come abreast of us and with more caution were able to ford

the creek. Again I began to sweat. Was this going to be the end of the

road?

After what seemed to be hours (actually a short time) a

tracked vehicle backed up to our truck, hooked on a tow rope and pulled us through

the creek to firm ground. Our driver returned and once more we moved slowly forward.

We reached the road and after a halt to allow other vehicles to cross the difficult

bypass, we got under way. The hills were now on the right side of the road and on

our left the ground fell sharply away to form a valley paralleling our course to the

south. Heavy small arms fire was coming down at the column from the high ground on

our right and the continual smack of slugs against the truck was unnerving to me, as

I expected any minute to be hit by the next one. A heavy‐set Korean soldier

was lying next to me and once when I turned to look his way I saw his jacket sleeve

jerk as a slug passed through. He just grunted and rolled his eyes. It had not hit

his arm and had missed me by inches. Again our truck stopped. This time the word

came back that another roadblock was holding up the column.

"On the way out on 1 December. The

soldiers are from M3/31, part of the rear guard. The two men lying in the foreground

are dead. The road is just over the bank (below) to the left. The trucks at this

time are about 100 yards behind me. A Chinese foot column is less than 100 yards to

the rear of the men pulling out. Heavy fire is coming from the hill in the

background. Time was about 1530 hours." ‐ MSG Wm. Donovan

SOME WOUNDED

GOT HIT AGAIN

To our left I could see ragged lines of Chinese troops

forming in the valley below, even though our covering aircraft dived on them time

and again. The Chinese were too far away for any effective rifle fire, but seeing

them reforming for new attacks was no comfort. On our right the enemy were in the

commanding spots on the ridges and were having a field day firing into our truck

column and its escorting guard. Wounded men in the trucks were getting additional

wounds and set up a mournful racket for someone to help them. Nothing could be done

for them. Officers began forming groups to flank the roadblock ahead and also to

clear the Chinese‐held hillside overlooking our column. The men were

reluctant to get going when they saw men on all sides of them being shot down by

Chinese fire. At first a few began to inch their way up the steep hill that began

abruptly at the roadside, then others joined. This action had a snowballing effect

and a platoon soon took the top of the ridge and then went over the other side. This

at least cleared part of the ridge, but fire was still coming from the roadblock and

the ridges to

the right front.

Dozens of soldiers

huddled and crouched around the trucks seeking protection and not heeding the call

of their officers to charge over the hill to support the initial group of GIs. The

dull boom of enemy mortars began a new tale. Out to our left the bursts began

creeping closer to our column. Included in this fire were deadly and much‐

feared white phosphorous shells which can burn the flesh right off one's bones

in seconds. About this time a wild‐eyed ROK soldier jumped into the truck and

flung himself on top of the wounded causing them to yell with new pain. He

wasn't wounded, just out of his head, I guess. But he wasn't so far out of

his head that he failed to recognize what I wanted of him when I picked up my

carbine and shoved the barrel in his face, yelling at him to get the hell out of the

truck. I was so mad at the s.o.b. for jumping in like that I would have gladly blown

his head off. He got out pronto and lost himself in the crowd of others milling in

the area.

As mortar fire continued to come closer I made up my

mind, despite my aching leg, to get out somehow. We had been stalled too long and it

was growing darker by the minute. No progress had been made in reducing the

roadblock and the Chinese were still pouring deadly fire from positions forward and

above us. I pulled myself out between the other wounded and dropped to the ground

behind the truck. I had the carbine with a full clip of ammunition ready to shoot.

Lt. [Charles] Curtis [I3/31]

hailed me and came up to join me in the ditch for a quick conference. We decided there was

only one thing to do – go over the hill as had the others, even though it meant taking

a chance of getting hit. To stay would lead to capture or eventually getting shot in the

truck. A decision was quickly reached to get going over the hill. Rallying about 20 other

men to go with us, we jumped up and scrambled up the hill firing as we went. We

couldn't see the Chinese but we knew where they were and could feel their fire coming

in and around us. My carbine fired two times, then failed to function. I threw it down,

picked up another from a dead GI, and kept going until we reached the top and safety on the

other side. We headed back toward the road on the far side [beyond] the enemy held

roadblock.

Map 8‐8a the Chosin Chronology

Click on the map for a full‐screen image; use your Back

button to return to this text.

Breakout east of Chosin.

The final killing ground was between Hill 1329 (just north of Hudong‐ni) and the

road, the hill having been occupied since the night of 27 November. The Chinese never did

launch a major attack against the Hudong‐ni perimeter, probably because of the

presence of the 31st Tank Company. After the Tank Company and others were withdrawn to

Hagaru‐ri on 30 November, the Chinese obviously adjusted their strength against the

units attempting the breakout from the north.

REMAINS OF A RELIEF

FORCE

As we arrived at the road it had grown dark. We could see the

burned‐out hulks of American tanks. This had been the limit of advance of the task

force [31st Tank Company] that tried in vain to relieve our surrounded force the day before

[two days before, 29 November]. We came upon Capt. [Earl H.] Jordan, M Company [3/31]

commander, who was organizing a group to knock out the roadblock from the rear. Once getting

his band together, he set off and was soon banging away in a firefight. It was quite dark by

then but we could see the flashes of gunfire. The group of 20 swelled to about 50 on the

road and they sat around or milled about trying to decide the next move. There was no

organization left. Men of all units were mixed up at this stage. Again Lt. Curtis and I came

to our decision as to what to do. We were going on to Hagaru‐ri where the marines

were holding, or where we thought they were holding. What lay between, we could only guess.

Maj. [Robert E.] Jones of the 32d Infantry [1/32] and Capt. [Ted] Goss from the 57th FA

Battalion [B/57FA] came up about this time and joined us with a few men they had led out. We

formed two long lines of soldiers on each side of the road and moved out quietly to the

south. As we moved along the group swelled in size until there must have been a hundred or

more.

Crossing another bridge that had been severely damaged, we ran into

an enemy outpost which immediately opened fire. Our troops dove off the road but kept going

forward. I was near the tail of the column, having dropped back as my leg began to stiffen

and slow me down. I had become separated from Lt. Curtis by that time, but Capt. Goss stayed

with me, which I appreciated. Being left behind was no rosy prospect. When the group hit the

sides of the road after being fired on they broke into two units, one going down a

narrow‐gauge railroad paralleling the dirt road, the other cutting sharply to the

right and hugging the frozen lakeshore [reservoir] path. I was with the latter group. We

were about 30 in number and actually had a better chance to move undetected through the

Chinese positions. We passed through a small logging village [Sasu‐ri] expecting any

minute to be ambushed, but got to the other side without incident. Another few miles and we

began to feel safer. This was short‐lived for we got another sharp challenge in

Chinese as we approached a bend in the path. We silently ducked to the right once more and

kept going. A few yards further we arrived at the ice of the reservoir and moved across an

inlet. After we moved about 800 yards a string of .50 caliber tracers licked out after us.

The Chinese were poor shots in the darkness and no one was hit, though a few rounds came

uncomfortably close.

Walk of the Long shadows. Men crossing the ice

of the reservoir, many footprints, a low sun causing long shadows, sun about to set.

This same photo appears on the dust cover of Roy Appleman's book EAST OF CHOSIN.

‐ Photo by MSG Ivan Long (the late LTC Ivan Long, USAR).

About 2230 hours

we could see flashes of machine gun and artillery fire in the distance. This was, in our

estimation, the site of the marines at Hagaru. Our big concern was that the Chinese

would have the town cut off from the north, the direction from which we were

approaching. We had no information on the marines' situation prior to our breakout

and it was anybody's guess as to the real picture up ahead.

HALT’ AND SAFE AT LAST

We held a council of war and decided that we would

risk it and move forward and take our chances. Staying overnight in the hills would

invite freezing and perhaps capture, so moving ahead seemed the best bet. With caution

and with greater intervals between men, we approached the flashes of fire, noise we

could hear loud and clear. About a hundred yards along the route we were startled by a

loud but unmistakable American "Halt!" Boy, that was the best word I had ever

heard in my life. The marines challenged us, then led us into their lines. We were safe

at last and could let down a little. They had been prepared for us as the aircraft

overhead had alerted them we would be coming out during the night. Hot food and medical

attention followed, then a place to sleep for the rest of the night. As I drifted off to

sleep that night I could say my prayers with full assurance that I had a lot of

assistance from the good Lord that day.

END NOTES

Although

Hugh Robbins has been cited as a source by historians Roy Appleman and others, we

believe it important that readers interested in Chosin see his complete manuscript. It

reflects the mind's eye of one person who experienced Chosin and survived to tell

his story, similar to those of Herb Bryant (CJ10.30.00) and Ted Magill (CJ12.15.02).

It's also important to understand the relationship between Robbins' experience

and previous journals (CJ11.27.03 on Mao's Generals) which provided limited insight

into the Chinese side. RCT 31 units confronted a large Chinese force that had launched

its main effort down the east side of the reservoir. Not only was the enemy delayed in

the mission of taking Hagaru‐ri, the tenacity of the Army units’

do‐or‐die defensive action for five nights and four days debilitated more

than two CCF divisions to the point where they were lost from further participation in

the Chosin campaign. In the west, the Chinese were no longer capable of cutting off

Marine regiments that launched their own breakout from Yudam‐ni at the same time

RCT 31 units were being destroyed at the east‐side anvil ‐ Hill 1221. From

then on it was downhill for the Chinese as their logistics system became a dribble while

most of their soldiers were "captured" by Father Winter.

END CJ 02.28.04

|