|

CHANGJIN JOURNAL 05.01.03

IN THIS ISSUE we continue our

series on the breakout from Hagaru‐ri to the coast where the units of X Corps are

busy preparing the Hungnam Perimeter. This presents the breakout from Koto‐ri to

the Funchilin Pass, with emphasis on the organization and operations of the Army

"Provisional Battalion" that is seldom covered in contemporary literature

about the Chosin campaign. In this coverage we will use extracts from Major General O.P.

Smith's "Aide Memoire" to highlight the Marine version of the story, then

later discuss the differences.

BREAKOUT FROM KOTO

BACKGROUND

Koto‐ri developed into one of the key

bastions of the 1MarDiv between the coast and the reservoir area. As of the night of 27

November when the CCF cut the road to Hagaru this became the Headquarters of Colonel

Puller's 1st Marine Regiment with the 2/1 Marines providing the perimeter force

until arrival of additional units. This was an interesting location, a small village

located four kilometers north of the pass and 11 miles south of Hagaru. One other road,

more like an improved trail, extended west to the hamlet of Hamadae‐ri, and from

there through the rugged mountains laden with switchbacks and villages supporting mining

operations, eventually arriving at the road between Sachang‐ni (1/7 Infantry,

3ID) and Yudam‐ni 30 miles to the north. A map study reveals this as hardly a

good route for deep envelopment by large forces.

Units at Koto began

to increase with the arrival of the 185th Engineer Bn on 28 November, a unit destined

for Hagaru where its attached D/10th Engineers was already located. That mission was

aborted when the 185th was assigned a sector of the Koto perimeter in a defensive role,

being reinforced by one platoon of the 44th Engineer Construction Bn. On 3 December the

battalion began construction of the Koto airstrip which was used by light aircraft, on 6

December by Navy TFBs and on 8‐9 December by C‐47s. A gift to the coming

engineer effort was the arrival of two 6‐ton Brockway bridge trucks of the 58th

Treadway Bridge Company with an attached platoon of the 512th Engineer Dump Truck

Company, units that at the time were hauling building materials for the Corps Advance CP

to be built at Hagaru. The supplies were quickly unloaded and put to use expanding

billeting and medical facilities for the expanding Koto perimeter, a great help to the

breakout force from Hagaru.

What was an advance CP of X Corps doing

way up here in the boonies north of the Funchilin Pass, a major MSR problem that

struggled to handle logistic support of one division? Was this General Almond's

nudge to get General Smith moving?

On 1 December the 2/31, the third

of Colonel MacLean's RCT 31 three infantry battalions arrived, after which F2/31

attacked and took the critical Hill 1328 which became part of the Koto perimeter, later

occupied by G2/31 until the withdrawal. Many 1MarDiv service and supply units, armor and

British Royal Marines, continued to arrive until the gatehouse bridge was finally

damaged beyond repair on 5 December.

8 DECEMBER ‐

KOTO TO THE PASS

The breakout plan from Koto south considered

the rugged terrain of the pass within which was the most important objective, the blown

bridge at the gatehouse. The approach included mountain ridges on both sides of the road

which had to be secured to protect the motorized column that would later uncoil from the

Koto perimeter into one long train. Once in the pass the terrain opens to the right

(west) while the road gradually descends along the steep slopes on the left (east). From

the pass it was about two kilometers to the gatehouse. The mountain ridge on the left

side of the road reaches its highest point in the pass, then rapidly ascends to terrain

including the gatehouse.

MAP 1:50,000 KOTO TO CHINHUNG

Click on the map for a full‐screen image; use

your Back button to return to this text.

This is a copy of a 1951 map very similar to the Japanese map

used in 1950, with 20 meter contour lines to show the viewer the difficult

terrain of the Funchilin Pass.

ENEMY

CONSIDERATIONS

It was known that the terrain west of the road was

critical. G Company 2/31 had been occupying the north end of that ridge at Hill 1328

where observers has seen columns of Chinese troops numbering inthousands marching

south, avoiding the perimeter at Koto as they moved to positions in their attempt to

stop the breakout. It was also known that the Chinese had been suffering from the

cold and were running low on supplies. They were a long way from their source of

supply beyond the Yalu River. Based on these facts, the plan assumed the Chinese

defense to be the ridges on both sides of the road.

There is more

to consider, that is, the combat capabilities and staying power of the CCF. Chinese

divisions arrived in the Chosin area with weapons and supplies carried on the backs

of soldiers; they had no logistical system to back them up at the time. When the

attacking units at Yudam and east of Chosin were bloodied and ran out of ammunition,

they were replaced by back‐up units. As a result they dissipated their combat

power on both sides of the reservoir and during two major attacks on Hagaru. After

that the Chinese combat capability was limited to manning fireblocks (Roy

Appleman's term). After that they were no longer looking for a fight, only

remained in their blocking positions to expend the last of their ammunition as the

Americans and British swept them aside. This theory is reinforced by the fact that

Koto had never received a major attack, although it was known that thousands of

Chinese were seen bypassing that perimeter. This can result in only one conclusion:

the Chinese were waiting for the Tenth Corps forces to leave North Korea as they

harassed the departure with immobile fireblocks manned by Chinese soldiers who

suffered the ravages of severe cold and malnutrition.

The flanks

had to be secured to allow the Brockway trucks with Treadway bridge sections to

reach the pass and protect the motor column to follow. Although indications were

limited, enemy movements around the east side of Koto to the pass remained a

possibility because the narrow gauge railroad moved around that side of the mountain

to the cableway south of the gatehouse. All of these considerations were essential

in developing an intelligence estimate of the situation. What no one could predict

was the weather.

The Air Force with support of the Army Airborne

riggers had been busy making test drops of Treadway bridge sections. Eight sections

were dropped from C‐119 aircraft in a designated drop zone at Koto. One was

damaged and another landed in enemy territory; six were enough. Bridge platoon

leader Lt. Charles C. Ward and his men then loaded sections to Brockway trucks of

the 58th Bridge Company and awaited orders to move to the Funchilin Pass.

As you follow the description of the breakout, study this map with

overlays that show the breakout for 8 December. Keep distance in mind: from the Koto

perimeter to the top of the pass is 2500 meters, from there the road goes downhill

to the gatehouse. This entire area was within range of artillery units at Koto, also

within range of 155mm howitzers of the Army 92d AFA Bn at Chinhung‐ni, both

depending on observation and communication.

BREAKOUT FROM KOTO TO FUNCHILIN PASS

‐ 8 December

Click on the map for a

full‐screen image; use your Back button to return to this

text.

Map 13‐1A from the CHOSIN

CHRONOLOGY © George A. Rasula, 1992, 2003.

MAJOR GENERAL O.P. SMITH

AIDE‐MEMOIRE

Here we insert an extract from Major

General O.P. Smith's Aide‐Memoire which highlights the major actions of

the breakout as reported to him by commanders and staff. Later we will explain what

actually happened.

Operations on 8

December.

After a quiet night at

Koto‐ri, the attack of RCT‐7 jumped off as scheduled at 0800, 8

December, as did the attack of the 1/1 Marines from Chinhung‐ni. A

blinding snowstorm that continued most of the day precluded the use of air

support and hampered operations of the ground units. RCT‐7 employed its

3/7 in the attack to seize Objective A. It met strong enemy opposition from the

objective. The 2/7 Marines was moved forward to assist the 3/7 by attacking from

the flank. The 1/7 Marines moved south astride the MSR prepared to attack and

seize Objective C when the attack on Objective A had progressed sufficiently to

warrant it. The Provisional Battalion USA, attached to RCT‐7, attacked

and seized Objective B without opposition and was pushed forward by RCT‐7

to the high ground south of Objective B and northwest of Objective D. From these

positions the Provisional Battalion was directed to send patrols forward to a

distance of 800 yards.

RCT‐5,

employing its 1/5, launched its attack on Objective D at 1200 and by 1425 had seized

it against light opposition. At 1530, C1/5 on Objective D was attacked by an enemy

group but forced the enemy to withdraw, employing only small arms and automatic

weapons. An estimated 50 to 75 dead were left by the enemy upon withdrawal. At 1700,

the Prov Bn USA moved into positions to the west of the 1/5 Marines and defenses

were consolidated for the night.

PROVISIONAL BATTALION 31/7

The plan called for two phases

in coordination with actions by 1/1 Marines at Chinhung‐ni. On 8 December the

7th Marines with 31/7 would take the high ground on both sides of the pass while 1/1

Marines would attack from Chinhung‐ni and take Hill 891. On the second day, 9

December, the 7th Marines and 31/7 would take the gatehouse and terrain protecting

it from the north, while the 1/1 Marines would continue uphill and take Hill 1081

which covered the gatehouse bridge site from the south. When this was

accom‐plished orders would be issued to move and secure the site after which

the Treadway bridge would be installed.

Once again the

Provisional Battalion (31/7) was attached to the 7th Marines with the Army taking

the left (east), one Marine battalion centered on the road and one taking the high

ground on the right (west). The MSR climbed gradually toward its highest point, then

began its winding way with many switchbacks on the left side of the gorge to the

base of the pass at Chinhung‐ni, location of the 1/1 Marines before relief by

Task Force Dog of the 3rd Division.

MAJOR

JONES

Due to many casualties [battle and cold injury],

Lt. Col. Anderson decided to form the remaining men into two companies, the

"31st Company" under Captain George Rasula and the "32d Company"

under Captain Robert Kitz. Major Jones acted as "Provisional Battalion"

commander of two rifle companies, while Lt. Col. Anderson as senior Army officer

present would continue as overall 31/7 commander maintaining contact with Colonel

Litzenberg. During this action the two companies had no supporting weapons and no

radios; infantrymen armed with rifles, carbines and grenades. Communication would be

by messenger.

CAPTAIN RASULA

About midnight Colonel Anderson had called for me, informing me that my company

would now consist of men from the 31st Infantry. At that time I didn't know our

casualties and cold weather injuries had reduced 31/7 from six rifle companies to

two, I and K. Frustration set in as I had no idea where the men were sleeping; they

were anywhere they could find shelter, a warm tent. Everyone was thankful that Koto

had not received a major attack by the Chinese.

Some of us had

the feeling we had it made; day‐by‐day it became more obvious the

Chinese did not have the capability of stopping this breakout. Mass was on our side.

Ten thousand from Hagaru was now fourteen thousand at Koto. We had the tents, food

and firepower, while the Chinese were a long way from the Yalu on this cold winter

night. I sensed a change in the weather; it was snowing.

LINE

OF DEPARTURE (LD)

Although we had been designated 31st and 32d

companies, I still called mine Item Company and I believe Kitz called his King

Company because he was its commander east of the reservoir. By morning when it was

time to cross the LD, I had a very small group led by lieutenants Parolari and

Holcomb. I left Lt. Escue back in the 2/31 area with the mission of finding every

man he could get his hands on and bringing them up to the first objective. The snow

continued with large flakes indicating slightly warmer weather.

It wasn't quite daylight, more like the term Beginning of Morning Nautical

Twilight (BMNT). The sky was a dark gray, cold and laden with snow. We crossed the

Line of Departure (LD) with visibility about twenty‐five meters, just enough

to see or be seen at close quarters. To move is to be seen. We were on the

move.

After pushing an uneventful 800 meters to the Objective B

we settled into a perimeter while waiting for Lt. Escue to join us with more men,

which he did in due time. The men who joined me were not only from the 31st, but

many artillerymen from the Hagaru breakout, led by Lt. Dale Smith and Lt.

"Jim" Wetherbee. Recalling their performance two days earlier, I wanted

them in upfront positions when we moved out. This delay gave us a few hours to get

organized and for platoon leaders to get to know who they had and assign leadership

positions. This also gave me time to study the map so as to get a feel for the

terrain we were about to cross. We also listened intently for activity to the right,

wanting to know what the 7th Marines and others were doing. The answer came in

muffled sounds of rifle fire telling us they had action around Objective A or down

below on the road. This immediately reminded me of the thousands of Chinese seen by

2/31 observers west of Hill 1328.

We soon got word to move south along

the ridge to the high ground above Objective C. The sky continued to spit cold dry

flakes. We knew nothing about the 1/7 Marines on the right, other than hearing the

sounds that told us they were engaged. When I finally received the order to continue the

attack I could see the gray curtain falling. It was snowing harder with each step. This

was cold snow, not wet and slippery but fluffy and silent. As the inches built up we had

to lift each step higher, concentrating on the silence afforded us by Mother Nature. I

gave thought to the value of skis and snowshoes as I kept an eye on the flanks as well

as the front.

Was Mother Nature favoring us or the enemy? As we

climbed I hoped others could see the beauty of nature I saw, forms and figures in black

and white, dancing as one moved forward keeping one eye on the flanks, senses nurtured

by my first eighteen winters in northern Minnesota. We soon measured our observation in

yards. It was almost the whiteout I had experienced in Nome, Alaska, during a maneuver

in January 1948, where one could only sense down by the pull of gravity. Here we were

fortunate, as the scrub pines laden with snow gave us a sense of dimension.

I stayed within sight of the lead scouts to make sure the company was going in

the right direction. Each step became more laborious as we climbed. The map said our

objective was about two thousand meters further up the ridge, and from there on it was

downhill all the way to the ocean. But first things first. This was not the time to

think of tomorrow, for it may never come. Today was today, now was now, and we

didn't know what was ahead. If the Chinese were covering this critical mountain

above the gatehouse, they surely must have a welcoming committee somewhere along this

ridge.

Slow down, pause, let the troops catch their breath, open

parkas to ventilate and evaporate the sweat. No time to change socks, that'll come

later. Think security: front, flanks, even the rear. In this silent winter‐white

we were alone. As we continued to climb the dancing snowflakes caused the dark shadows

in the scrub pines to move, making one think of the enemy, but they weren't there,

yet. We were on a great white stage, performers readying the final act.

I paused often to check the map because reading a summer map in winter is to

be tricked into believing what you want to believe, to make you think you're on the

crest when you aren't. I began to issue instructions to settle into a perimeter,

thinking this was the objective, mind flashing through the infantry

manual‐‐perimeter security, defense, outposts, communications, take care

of the men, all those things.

Suddenly the final act began with a

burst of automatic fire from the front, a Thompson sub and other weapons to my left

front, bursts of fire breaking the silence like the crescendo of drumsticks on the rim

of a snare drum. It was that all‐powerful noise of combat that commanded

attention as silence abruptly disappeared. Friendly action took over as the lead

soldiers began spraying virgin white snow in search of the color red. The Reaper was at

hand. But who, which side, would reap the most?

Everything went on

automatic. Build up base of fire and get a flanker going. Use the right flank.

Friendlies were in that direction so their rear might be covered, who knows?

Escue's platoon was already moving through the deep snow on the right as the lead

platoon leader on my left, motivated by the loss of four soldiers, led the assault on

the left. LT Smith rose and with blood‐ curdling yells launched their attack

through the deep snow, firing as they went. The Chinese soldiers had no idea what hit

them as they fell or did their best to escape.

It was soon over as

silence reigned once again while those behind us wondered what had happened. Was silence

victory? Or was it just a pause waiting for the next violent act as the snow continued

to fall on this battlefield overlooking the valley below the pass. The dead lay silent,

spreading patches of red on the white snow. Get the wounded down to the truck column

where the medics are, that is, if we can find them. Get them off this mountain before

they freeze to death.

As this phase ended the clouds above

began to break, telling us the weather was about to change once again. It was getting

dark. We could see where we were, high in the pass looking at the gatehouse and road far

below. There were no battle noises as I looked at the white snowpack covering the steep

slope, reminding me of my first ski jump on a big hill, at the moment sensing the same

thrill which had to be the thrill of victory. The empty foxholes had been oriented

toward the south and the road below, a defense position prepared for use against the

Marines when they first moved north to the Kaema plateau, now home of the famous

"Frozen Chosin." Now it was a cold mountaintop covered with deep snow where

the occupant held title to the land. The End of Evening Nautical Twilight (EENT) passed

rapidly as darkness settled in. And so did the greater enemy, the cold, as it consumed

this mountain pass on a night when animals sought warmth deep in their burrows.

Nostrils smarted as men breathed. This was going to be a three‐dog

night, 20 to 30 below with the wind chill. It was a night for looking after the

soldiers. There would be no counterattack by an enemy who was suffering this same

intense cold. Having seen the ill‐clothed Chinese around this position left no

doubt they'd be seeking shelter, withdrawing into themselves as anyone would in

this weather. The dead turned to stiff logs and blackened faces sculpted by The Reaper.

The deep freeze was at work.

Stomp your feet, keep moving, change

your socks quickly so you don't freeze your feet and hands; beat your arms like a

flying bird to keep the blood flowing. Stay alive, as down that pass was the next

objective, warmer weather and friendly faces. Eat your rations, but don't eat it

frozen, just suck on it like it's the 4th of July and let it melt in your mouth as

you swallow the juices. Suck your Tootsie Rolls like a child enjoys his candy, one after

another. Stoke the furnace in your belly. You'll need it, it's going to be a

cold night. By this time I had many good lieutenants to keep watch over the troops.

Being the elder and commander, I was tired.

I was also fortunate to

have one of the Chinese foxholes, a little one about four feet deep, almost five feet

long, barely wide enough for my shoulders, and as luck would have it, a empty ammo box

to sit on. It didn't take long to figure out how to make use of the hole. First, I

knew I wasn't about to get into my sleeping bag, even though I felt the enemy would

not attack. Taking out my knife, I cut the bag full length and made a comforter out of

it. Then I adjusted the ammo box to sit on and get my body into a leaning‐back

position, after which I covered myself from end to end with the sleeping bag, making

sure the feet were covered and the sides tucked in, then pulled the bag over my head.

That was all there was to it. From then on it was wiggling toes and fingers and

listening to the sentries and others as they shuffled to keep warm in the starlight of

this frigid night. I hoped it would snow again to add more insulation to my nest. When I

fell asleep or how long I slept I don't remember, but I did sleep.

PROVISIONAL REVIEW

The operation plan for

this breakout was major improvement over the last because it had designated objectives

on the overlay that I had transferred to my map. I considered Objectives B and C my

objectives and I would have to keep an eye on my left flank, Objective D (Hill 1457).

Although C was shown on the overlay as the hillside above the road, I made it the

highest ground, the west finger of Hill 1457 because the nose of that hill went straight

down to the blown bridge.

The OPS report states the Prov Bn seized

Obj B and was "pushed forward ...to the high ground south of Obj B and NW of Obj

D." Item Company received instructions by messenger to continue the advance. To

identify "the high ground" as described was impossible in a snowstorm since

this was one long mountain ridge with gradual gradations that continued to rise to the

final crest above the pass. The slight changes in terrain were impossible to identify in

a snowstorm because one's position could not be related to other terrain features.

As the lead provisional company I continued until we encountered the enemy on the final

objective, the highest point on the left side of the MSR.

The sketch maps we have seen in

various books differ, being the author's interpretation of the first map published

in the official USMC history, Volume III, The Chosin Reservoir Campaign. This map from

the Chosin Chronology is different because its basis is an accurate topographic map

which gives the viewer an appreciation for the terrain, showing that Hill 1457 is not

the dominant terrain, but part of a wishbone‐shaped mountain where the section

next to the MSR is actually dominates the area of the gatehouse and its blown bridge.

The numbered Hill 1457 is secondary. We don't know exactly where the 1/5 went in

that snowstorm when they launched their attack on Objective D, but they were not on Hill

1457 at daylight 9 December.

The location of Objective C in the

official history is confusing in that it shows but an arrow pointing uphill from the

MSR. When we look at Map 16 in Appleman's Escaping the Trap we do not find

objective designations, only hill numbers, arrows and unit designations.

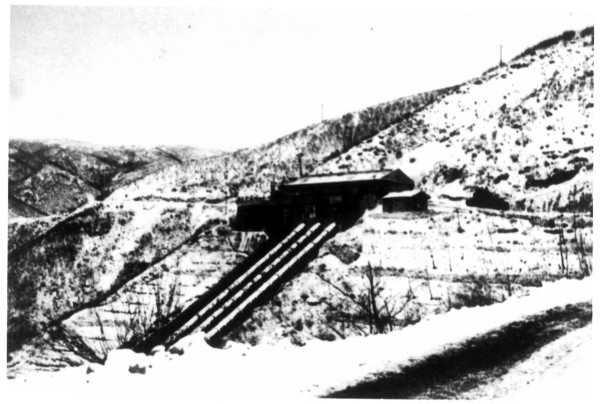

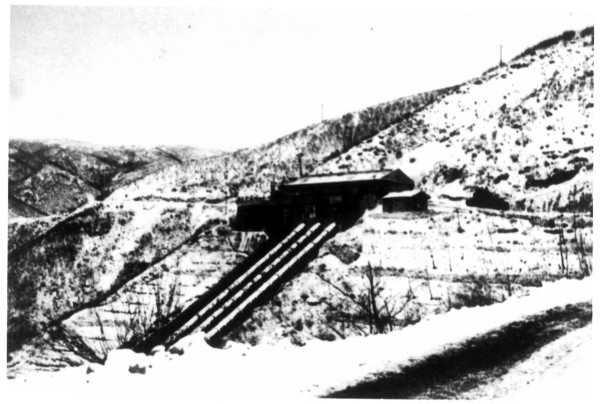

Gatehouse in Snow

Although the original photo is but a 3x5

inch print of 1950 vintage, it is included here to show the difficult terrain around

the gatehouse. The mountain rising high above in rear of the gatehouse was the

location of the Army provisional company at this time in the story.

GEN O.P. SMITH'S

AIDE‐MEMOIRE

The Treadway bridge

spans, which had been dropped at Koto‐ri on 7 December, were moved forward

with the advance out of Koto‐ri. At one time during the day the bridge train

was about a mile in advance of the CP of RCT‐7. The ExO of RCT‐7,

feeling the bridge train was too far ahead, directed it to return to the vicinity of

the CP. When this location came under enemy mortar fire, the bridge train was pulled

back about 1 1/2 miles and protected by tanks. By this time it was dark and the

engineers had to wait for the morning of 9 December before they could move to the

bridge site. [The Koto perimeter was receiving harassing small arms fire at this

time while adjustments were being made in the perimeter.]

When the 1/5 Marines moved out of the perimeter at 1200, RCT‐1 used

the 2/5 Marines to reinforce the northern perimeter between D and C, 2/1 Marines. H

3/5 was used to extend the defensive perimeter ot the south. H and I 3/1 Marines

relieved elements of the 185th Negro (C) Bn and C Co 1st Negro Bn in the defensive

perimeter. These engineer units had been holding positions in the perimeter defense

east and southwest of Koto‐ri. The engineers began preparations for

destroying damaged ammunition and all that could not be transported in available

vehicles. RCT‐1 also had to hold back about 3500 civilian refugees who were

crowding the perimeter from the north. [MacArthur's scorched earth

policy‐‐destruction of homes and livelihood ‐‐ resulted

in a major exodus by local civilians. In this terrain and climate the only

possibility for survival was walking to the coastal area of Hungnam.]

On 9 December, preparatory to withdrawing from

Koto‐ri, RCT‐1 relieved the 3/1 Marines in its positions on the

perimeter with the 41st Ind. Commandos, R.M.. the 3/1, at 1530, 9 December, moved

out to occupy Objective B and to relieve the 3/7 Marines on Objective A. The relief

was completed at 1800. The 2/7 Marines had previously been withdrawn from Objective

A to an assembly area nearby. The 1/7 Marines, less the company on Hill 1304

(Objective C), was directed to outpost the MSR between Objective C and the 1/1

Marines in the vicinity of Hill 1081. The 2/7 Marines, less a company with the

regimental train, outposted the MSR between Objective A and Objective C. The 3/7

Marines upon being relieved on Objective A moved to positions on Objective C and

tied in with the company of the 1/7 Marines for the night. [Bridge was being

installed.]

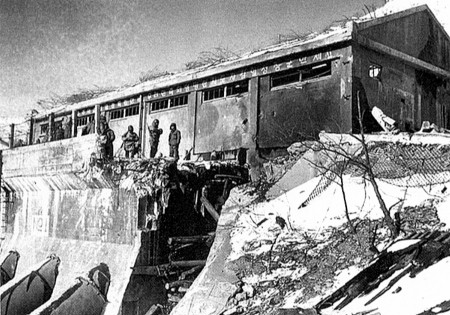

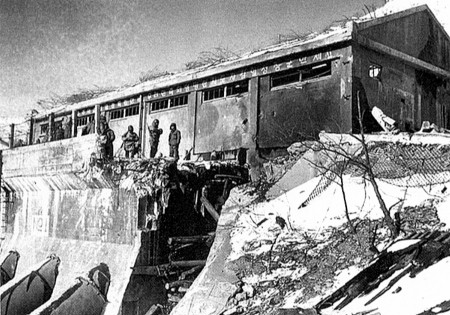

Blown Bridge

Department

of Defense Photo (USMC) 5376.

AIDE‐MEMOIRE CONTINUES

...

RCT‐5, less 1/5 on Objective

D, made preparations during the afternoon of 9 December to move out along the MSR

the following day.

With the bridge at the

penstocks, 3 1/2 miles south of Koto‐ri, nearing completion and all

objectives having been occupied, the regimental and division trains were started

down the road out of Koto‐ri. the departure of the trains from Koto‐ri

had been timed so that leading vehicles of the trains would reach the bridge at

approximately the time it was completed. At 1630, 9 December, the trains were moving

through Funchilin Pass enroute to the bridge.

At 2330, 9 December,

the Division Rear CP at Hungnam received OI 27 which directed the Division, upon arrival

at Hungnam, to embark without delay for Pusan.

At

1800, 9 December, the Deputy Chief of Staff of the Division (Colonel Snedeker) opened

the advance CP of the Division at Chinhung‐ni, which was to control the movement

of Division elements from Chinhung‐ni to the south.

Throughout the day of 9 December, civilians refugees continued to gather north

of the perimeter of Koto‐ri. they numbered about 3500. It was necessary to drive

them back by firing over their heads. this was a proper precaution as the CCF were

infiltrating into their ranks.

The perimeter of

Koto‐ri received heavy small arms fire from the southwest during the day but no

attack developed. Much enemy activity was noted to the north, east, and west of the

perimeter and air strikes and artillery fire were placed on observed enemy groups. In

several instances, the artillery employed direct fire on close‐in enemy groups.

BREAKOUT FROM KOTO TO CHINHUNG, 9

December

Click on the map for a

full‐screen image; use your Back button to return to this

text.

Map 13‐1B from the CHOSIN CHRONOLOGY © George A. Rasula, 1992,

2003

PROVISIONAL BATTALION continues ...

daylight 9 December

Suddenly I heard voices, men talking

in normal tone, no shooting. As I eased back the cover from my face I realized I was

covered with six inches of new snow, the insulation kept me warm and made possible

my sleep. As I eased out of my cozy shelter I saw that the sky was clear, and from

that lofty point above the pass it seemed we could see into eternity, an amazing

sight to look down to see pieces of the road winding down the Funchilin

Pass.

As I rolled up my sleeping bag and tied it to my pack I was

called over to the east side of the perimeter. There off the the east on Hill 1457

stood three Chinese or North Koreans who, by their dress, appeared to be officers.

My soldiers immediately asked permission to take them under fire. When I look at my

map, judging the distance to be more than 500 meters, I asked for someone who had

shot expert the last time on the rifle range. When he came up I told him to get down

in the prone position and adjust his sling and sight just as he would on a range,

and take into consideration the Manchurian wind from the left, then squeeze off one

round. That one shot disturbed the morning calm as it resonated up and down the

valley. Then silence, as the three officers casually turned and walked behind the

hill. We didn't see anyone else from that moment on, convincing me the extreme

cold of the previous night had taken its toll of the ill fed and underdressed

Chinese soldiers.

I then turned to more important matters,

seeking relief for my soldiers before we suffered more casualties. We had suffered

more casualties from cold the previous night than we had suffered all the way from

Hagaru. The wind was picking up as the high was setting in with clear sky and severe

cold, direct sun on the skin being the only warmth one could feel. Since Lt. Col.

Anderson knew nothing of our situation, I had Lt. Escue accompany me as we

backtracked along the ridge line and then took a long diagonal through the deep snow

to the road below. Walking among the column of 7th Marine vehicles it didn't

take long to find the Provisional Battalion command group, with Anderson sitting in

a jeep encased in a GI blanket. As I brief him and received his nods of recognition,

I wondered if I was really making my point. Eventually he said "I'll see

what I can do." At this time I didn't know that units of the 5th Marines

were somewhere in my area, nor was I told. As I turned to leave Corporal Coate, the

S‐3 clerk, presented me with a warm can of C‐rations that he had been

preparing on the engine block, the food warmer of all truck drivers. As I savored

the pork and beans I was reminded that the pancakes at Koto had been my only food

since Hagaru. I looked at the pork and beans as dessert, not knowing, other than a

pocket full of Tootsie Rolls, where the next meal was coming from.

Before I saw Anderson I didn't know what was going on, other than

that the 7th Marines were to our right, to the west on the other side of the road,

and to the east was no‐man's land, the enemy or nothing but snow and

Siberian tigers and bears in hibernation.

I learned that the 1/1 Marines had

been attacking north from Chinhung‐ni, and today would be taking Hill 1081 which

was below and two thousand meters from my mountain. I also learned that the lead

battalion of the 7th Marines was meeting Kitz's Company at the gatehouse and the

bridge repair was about to begin. Things were looking up, but I was still concerned

about my men suffering from frostbite as well as hunger and exhaustion. As the day wore

on the wind‐chill would increase; it always happens when a blue‐sky high

moves in.

I have a vivid memory of that trek down and up the

mountain. It was a Korean cemetery, a group of organized mounds covered with snow, like

those I remember seeing during my earlier tour in South Korea. It was an eerie feeling,

thinking that those mounds were Chinese soldiers who had gone to sleep under their

quilts, now frozen stiff.

It was later that day when a company of the

5th Marines that had been somewhere behind us the previous day finally arrived. It

wasn't a formal relief, just giving up real estate as we moved down the mountain to

another position closer to the gatehouse and the road where Captain Kitz's King

Company had been located. Years later I saw a photo of the blown bridge with as many

Army helmets and parka shells as Marine gear. We enjoyed the new location because it was

protected from the cold wind and most important, it was close to the road with the lead

battalion of the 7th Marines. We'd be the first out.

From then

on it seemed to be a long time waiting for the Engineers to install the Treadway bridge.

Eventually we began the long walk down the switch backs of the Funchilin Pass to

Chinhung‐ni. For the roller coaster enthusiasts it was a thrill to walk down the

twisting and slippery road, although for acrophobia it was often sheer terror, feeling

that a slip would catapult one over a cliff. But that was imagination working because

while the slope below the road was very steep, it was hardly a cliff. I recall on one

occasion when a mess truck suddenly gasped its last breath. We listened as it was pushed

over the side, hearing the pots and pans rattling far down the mountain.

Eventually we met units of Task Force Dog of the 3d Infantry Division in the

area of Chinhung, noting the immense ammunition and ration dumps, supplies that had been

destined for units north of the Pass when the road was cut. I wondered how much would be

destroyed by the Dog Engineers before they pulled out behind the 1MarDiv, knowing the

dumps at Koto as well as Chinhung would be targets of the Korean refugees as well as

Chinese soldiers. We hoped the women and children we had seen would get food and

blankets, although we were sure Chinese rifles would control the distribution.

We sensed warmer weather as we hobbled along on feet trying hard to take the

next step in those uncomfortable shoepacs, footgear not made for long marches. None of

us knew the distance from Hagaru, but we felt the pain. South of Chinhung‐ni we

eventually came to an assembly area of trucks pointed toward Hamhung. When we loaded our

small company and headed south we had to fight to stay awake because of the possibility

of ambushes.

Far to the south we were stopped by an MP and given

directions to the assembly area of the 31st Infantry. There guides led us to a warm

tents with canvas cots and sleeping bags. Many collapsed into fitful

nightmares.

Meanwhile back at Koto aerial evacuation had been taking

place, the last of which were taken out on C‐47s and Navy aircraft, among the

wounded was Major Witte of the Provisional Battalion who had made it that far on the

back of a tank. We learned years later that lieutenants Boyer and Rollin Skilton, both

killed on 6 December during the breakout from Hagaru, were among the 124 marines,

soldiers and British commandos, interred in the mass grave at Koto.

MASS GRAVE CEREMONY AT KOTO

Burial ceremony at the mass grave during the snowstorm on 8 December.

Photo courtesy 41 Commando, Royal Marines.

When the Provisional Battalion

31/7 finally closed with the 7th Marines at Hamhung , there were still thousands of

troops and vehicles stretched all the way back to Koto where Puller's 1st

Marines would cover the rear with armor units being last to negotiate the

treacherous Funchilin Pass. Tanks were positioned last in the column because of

possible breakdowns blocking the narrow road. CPT Bob Drake, commander of the 31st

Tank Company, had the foresight to position his lighter tracks ahead of the heavier

Marine tanks, a wise move considering what happened.

Troops of the 41 Commando,

Royal Marines moving through the Funchilin Pass

at a time when

weather conditions varied by the hour, depending on where they were in the

pass.

THE FINAL WITHDRAWAL

‐ KOTO TO THE HUNGNAM PERIMETER

Map 14‐1 from the CHOSIN

CHRONOLOGY

Click on the map for a

full‐screen image; use your Back button to return to this

text.

© George A. Rasula 1992, 2003

GEN SMITH REPORTS TANK

LOSS

At 2400, 10 December, the tank

column moved out with the Tank Co, 31st Inf leading, followed by B and D 1st Tank

Bn, in that order. The Tank Platoon of the AT Co 5th Marines was attached to D Co.

The Div Recon Co had placed only one platoon at the rear of the tank column, ...

.

Along the icy mountain road south of the pass

the tanks moved slowly with lights on and dismounted crew members acting as guides.

With the high cliff [sic] on the left side and a sharp drop on the right, tank guns

were useless for fire to the flanks. Only the leading and rear tanks could fire to

the front and rear, respectively. ... With frequent stops due to holdups in the

column ahead, the Korean refugees with intermixed CCF troops kept approaching the

last tank in the column.

At about 0100, 11

December, the ninth tank from the tail of the column had a brake lock holding up the

remainder of the column. ...

The tank whose

brake was locked was pushed off the road to a ditch on the left, it being impossible

to push it off the downhill side. The next two tanks behind this one moved around

the abandoned tank. Then the brake on the leading tank became locked. This blocked

the road and, with the enemy exerting heavy pressure, the word was passed to abandon

the immobilized tanks. After this the tank driver managed to release the brake of

the tank having the second brake lock and this tank and one behind it moved out.

However, the remaining tanks had already been abandoned. The covering platoon of the

Div Recon Co suffered fourteen casualties, one officer and eleven men wounded and

two men missing in action, while several casualties were sustained by tank

personnel.

The decision to place the tanks last

in the Division column proved to be a very sound one. It is apparent now that had an

adequate infantry rear guard been provided and had the 2/1 Marines remained on Obj D

until the column had passed, the pressure on the tank column might have been avoided

and at least 6 of the 7 abandoned tanks might well have been brought out. . . . It

is accepted that tanks required infantry protection against close in attack, which

was particularly necessary in this case where the firepower of the tanks was greatly

restricted by the terrain and the road conditions.

THE FINAL WITHDRAWAL

Soon it was a matter of folding in

rear units from their positions on the high ground protecting the MSR, withdrawing

as they continued to watch the rear and flanks. As the tail of the 1MarDiv passed

Chinhung the responsibility for the rear became that of Task Force Dog, and as Dog

withdrew into the protective outpost line of the Hungnam Perimeter they disbanded

and returned to parent units.

The area around Sudong remained a

thorn in the side of both Marines and units of Task Force Dog. Even before the

breakout supply convoys were attacked in that area, later attacking the withdrawing

force. Gen. Smith reports "Just after midnight 10‐11 December the

regimental train of RCT‐1 was ambushed at Sudong by an enemy force ... . In

the resulting action six vehicles were lost and the casualties sustained amounted to

eight killed and 31 wounded. This was a bitter loss, as RCT‐1 had assumed hat

the movement was being covered by protective force." During 11 December similar

but lesser enemy action was experienced by withdrawing units of 1/5 Marines and 1/1

Marines. We regret that the withdrawing units "had assumed" they were

secure in that narrow gorge area south of Chinhung [See topo map]. Security is a

command responsibility that cannot be delegated to units assumed to be in the

area.

Task Force Dog will be a separate story for a future issue

of the Changjin Journal because, as we research its background, we find various

versions of their composition and accomplishments. One book reports they had one

infantry battalion, while another reports five. We continue to search sources.

When the 1MarDiv with attached units

closed into the Hungnam perimeter the mission stated in X Corps OI‐27 was

"on arrival at Hungnam embark without delay for Pusan." This they did, and

fortunately for soldiers of the Provisional Battalion, they too embarked with the

1MarDiv and sailed for Pusan.

END NOTES

This concludes our coverage of Provisional Battalion units during the breakout

from Koto to the Hungnam perimeter. Since this story involved many other units operating

within the same timeframe, we will attempt to cover them in brief segments of future

journals. Noted is the limited coverage of other companies, especially the 32d Company

(King Company) commanded by Captain Kitz, regretting that available resources including

the after‐action report of Captain Kitz contain very little detail about the

phase from Koto to the south. During this writing we have come upon the need for

coverage about the use of armor and artillery during the Chosin campaign. Since very

little is available on these subjects we invited essays on these subjects for use in

future journals.

End CJ 05.01.03

|