|

CHANGJIN JOURNAL 12.15.02

IN THIS ISSUE we look back

from our fifty‐second anniversary of the Chosin breakout at the 57th Field

Artillery Battalion that was attached to the 31stRegimental Combat Team (RCT 31) east of

the Changjin Reservoir. We are reminded that Charlie Battery had been detached prior to

the move to Chosin, although A Battery of the 31st FA Battalion (155mm) had been

attached; the battery did not arrive before the Chinese cut the MSR on 27 November 1950.

The basis for this presentation is a letter from Colonel

Edward L. Magill, JAGC, USAR (Ret) to Roy E. Appleman, written shortly after reading

Appleman's book Escaping the Trap. This was also the basis for

"Ted" Magill's presentation of the artillery story at a Chosin Few

reunion that resulted in a favorable change in the attitude of many Marines about the

performance of Army units at Chosin.

57th FIELD ARTILLERY BATTALION

After occupying a

non‐tactical position in the late afternoon, Baker Battery settled down for the

night. Lt. Morrison fired registration rounds but there was no other firing. During the

early evening, a few Korean refugees passed through our position and indicated that they

had seen a large number of soldiers to the north. Nobody took them seriously. The

evening of 27/28 was not too bad from our standpoint. We did not know that Item, Love

and King Companies and Able Battery were under attack until well after midnight. The

first thing that alerted us was the sound of bugles. Oddly enough, we did not hear much

small arms or mortar fire from their positions farther north in the inlet until early in

the morning. We received some small arms fire in our position but not a great deal.

Initially, the Chinese attacked Item, Love, King Companies, and Able Battery north of us

and Headquarters Battery to our south, but bypassed Baker Battery for awhile. At dawn,

men from Love, King, Item Companies and Able Battery filtered back into our position.

When daylight arrived, we could see that the Chinese had pulled out of the Able Battery

position and had not removed or damaged its guns. We then moved farther north and went

into position in the inlet next to Able Battery. After the move, all of the 3rd

Battalion and its supporting units were within the inlet perimeter. Generally speaking,

the Able Battery guns were emplaced on the east side of the perimeter, aimed in a

northerly direction, and the Baker Battery guns were located on the west side of the

perimeter, aimed in a southerly direction. Each battery was responsible for covering

half of the perimeter. Baker Battery's westernmost gun was very close to the

railroad track. It was probably not more than 50 feet from Sgt. Branford R. Brown's

M‐l9. (See map 9, page 117.) The guns were not well dug in because of the frozen

condition of the ground.

During the nights of 27/28

and 28/29, I was primarily concerned with the local defense of the battery. The same

situation was true for Lts. Eichorn, Tackus and Smithey. Unfortunately, on the night of

28/29, Baker Battery suffered extremely heavy casualties. Lts. Morrison and Stysinger

were both killed. Lt. Anderson was seriously wounded. All the rest sustained minor

wounds and were beginning to have frostbite problems. But they all could function. We

lost four chiefs of section and numerous cannoneers. Sgt. Nitze, a chief of section, was

decapitated when a mortar round landed on his helmet. Gun crews were firing almost all

night long. Of necessity, firing battery personnel were standing on top of the ground,

servicing their guns. Consequently, they sustained heavy casualties from mortar fire.

Mortar shells exploded almost at the instant of impact because of the frozen ground. The

explosions caused maximum fragmentation and concussion effect.

During the battle at the

inlet, Baker Battery did not operate under battalion control. Almost all of our

artillery fire was direct. We were covering the ridgelines and the avenues of ingress

into the southern half of the perimeter. At times, our gun tubes were depressed as far

as possible and fired so that the shells would ricochet off the frozen ground and obtain

maximum fragmentation effect against the advancing Chinese infantry. Fuses were set at

minimum arming range. During the early morning of November 29, I became the "de

facto" battery commander. By that time, we were already very short of food, water,

artillery shells, small arms ammunition and manpower. There was very little medical

assistance available for the wounded, many of whom simply froze to death. We had

received some air resupply, but it was spotty at best and a substantial part of the air

drop supplies fell into areas controlled by the Chinese.

I was quite surprised when the 1st Battalion, 32nd Infantry Regiment, arrived

at the inlet on the morning of November 29. Nobody had mentioned to me that there was

another infantry battalion in the area. The arrival of this unit was very heartening as

we certainly needed the additional troop strength. On page 114, you mentioned that

nobody from the 57th Field Artillery saw Col. Alan D. MacLean as he traveled across the

ice next to the bridge approaching the perimeter. Actually, Sgts. Copelan, Brown and I

all saw him coming across the ice. We were standing next to Sgt Brown's M‐l9

when we saw him come out onto the ice and move toward the perimeter. He was a large man

and we had a clear line of sight. At the time, we did not know who he was and did not

learn his identity until later. He was hit several times and staggered, fell and finally

was led off the ice by what appeared to be Chinese soldiers. Some friendly troops on the

south side of the bridge were trying to assist Col. MacLean but were unable to reach him

in time. While this was going on, vehicles from the 1st Battalion were erratically

crossing the inlet bridge at high speed.

At the time

Col. MacLean was crossing the ice toward the perimeter, Baker Battery and the

M‐16s and M‐19s of D Battery, 15th AAA, were heavily engaged trying to

contain a Chinese attack from the south. Consequently, these units were not able to

direct their attention toward the inlet bridge approach to the perimeter.

In my opinion, there are two men who have never received

proper credit for their contribution to the inlet defense. They are Sgts. Brown, D

Battery, 15th AAA Battalion, and Edgar Copelan. Sgt. Brown commanded an M‐l9 and

was especially skilled in directing the fire of its twin (dual) 40s. He was a very

courageous and capable NC0 who performed exceptionally well during the entire battle.

The most impressive thing about him was his calmness and good humor under the most

trying of circumstances. Sgt. Copelan was Baker Battery's chief of firing battery.

He had combat experience in Europe during

World War II. He was also an

outstanding NC0 who was thoroughly proficient in the use of the 105s. He played a key

role in keeping Baker Battery's guns manned and firing. Like Sgt. Brown, Sgt.

Copelan was very calm and good‐humored throughout the ordeal. These two men

performed magnificently and provided great inspiration for their soldiers. And, they

certainly were of immense help to me in operating the firing battery.

The night of 29/30 was not as bad as the previous night. By then, the

perimeter defense had been reorganized to incorporate the units of the 1st Battalion,

32nd Infantry, which strengthened the perimeter defense. However, the

ever‐increasing number of casualties was becoming a critical problem. The men

were very concerned about being hit because they knew there was a good chance that they

would freeze to death if they were immobilized. The remaining medical personnel were

close to exhaustion and there were few medical supplies. There was no satisfactory cover

for the wounded who were unable to ambulate. Truck tarpaulins and supply parachutes were

used to cover the wounded wherever possible. I kept telling Lt. Anderson that he would

probably be evacuated by helicopter although I knew that was unlikely. He was well aware

of the situation even though he was critically wounded. Supplies of food, water and

ammunition were being rapidly depleted. Remarkably, the troops remained in pretty good

spirits, everything considered. What they lacked in unit training and experience, they

more than made up for in courage and determination. By November 30 Baker Battery was

down to five, later four, guns.

The two helicopter medical evacuation flights

that removed a small number of wounded from the inlet on November 29, provided some

temporary encouragement to the wounded men. They began telling themselves that other

helicopters would come in later and evacuate the most seriously wounded. That, of

course, was not to be.

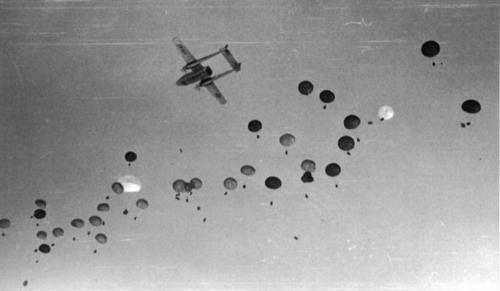

The Inlet perimeter. In center of picture

are three helicopters that landed to pick up wounded, landed about 400 yards SW of

the bridge. In center foreground is mortar position of L Company, 3/31. Man in photo

by the hole is squad leader Sgt. Luther Crump.‐‐ Photo

courtesy William Donovan, L3/31/7.

When Maj. Gen. David G. Barr flew into the

position on Nov. 30, his helicopter landed a short distance east of Sgt.

Brown's M‐l9. He was met by a couple of officers who took him to find

Lt. Col. Don Faith. After his meeting with Col. Faith, he returned to his helicopter

and immediately left the inlet. He did not spend any time trying to encourage the

troops. In retrospect, Gen. Barr must have decided that the battle was about over

for the perimeter defenders and that there was little chance of any of them

surviving the engagement. That's the only logical conclusion one can reach as

to why the 31st Infantry Rear and 31st Tank Company were ordered to withdraw from

Hudong‐ni to Hagaru‐ri on the afternoon of Nov. 30. Gen. Barr had to

realize that withdrawing those units eliminated any chance the troops at the inlet

had of completing the trek to Hagaru‐ri as an effective fighting force. Had

the tank company and supporting troops remained, the inlet force would have had a

much better chance of remaining substantially intact, including the truck column,

and successfully making its way to Hagaru‐ri. [Note: At the time Gen. Barr

visited the Inlet units he was not in command of those units, for on the previous

night all Army units in the Chosin area had been attached to the 1st Marine

Division. ‐ Editor]

The fighting was fierce all through the

night of 30/1. Baker Battery had a direct field telephone line to the infantry units on

the south side of the perimeter that was being manned by Lt. Keith E. Sickafoose, 57th

Field Artillery, who was directing the fire. I can still hear him saying, "Oh

s‐‐‐! They've broken through again." (Lt. Sickafoose was

a USMA graduate, Class of '49.) We were firing direct at minimum arming range. We

used up most of our remaining HE shells with point detonating fuses. By daylight the

Chinese had fought their way into the Baker Battery gun position. A group of Chinese

infantrymen infiltrated the position by moving along the railroad track from the south

and were lobbing hand grenades over the embankment. They were killed near the 105s. One

Chinese soldier came running toward me s I stood next to a 105. Some of the cannoneers

were yelling at me to shoot him but he was wearing a GI field jacket and I thought he

was an American. He jumped on me, wrapped his legs around my waist and started hitting

me on the helmet with a "potato masher" hand grenade. Fortunately the grenade

didn't go off and I killed him with a carbine bayonet that was tucked in my boot.

The cannoneers thought it was pretty funny. When daylight came, Baker Battery was in

very tough shape. We had almost no ammunition left and only four guns that would shoot.

I had three hand grenades, and 22 rounds of carbine ammunition, a carbine bayonet and a

carbine that wouldn't fire. Fortunately, the Chinese withdrew shortly after

daylight rather than follow up with one more determined infantry attack which probably

would have succeeded in overrunning the position.

Two 105mm with crews, pointed left and right.

Haze in the air may indicate early morning fog and firing of the guns. Low barrel

position of gun on right indicates it had been firing "direct fire" at

attacking Chinese. ‐‐ Photo courtesy Ivan Long, Hq/31/7

BREAKOUT

The sky was overcast and

there was no air cover. We tried to police up the position, distribute what little

ammunition was left and prepare for the next attack. A section chief, Sgt. Hodge, gave

me part of a half of a frozen peach. That was all the food he had left. While we were

discussing our predicament, an opening appeared in the overcast and a couple of Corsairs

came through providing us with some much‐needed air cover.

During mid‐morning, word filtered down that we were going to try

to break out of the perimeter and proceed to Hagaru‐ri. Subsequently, we unloaded

all of the trucks that would run. The only items left on the trucks were tarpaulins.

Whatever gasoline was available was put into the trucks. When the unloading job was

completed, there were 23 trucks ready to be loaded with wounded. Throughout the morning

we received sporadic mortar fire and automatic weapons fire causing numerous additional

casualties. I was hit in the legs by mortar fragments. The same round killed two of my

NCOs.

We decided to put Sgt. Brown's

M‐l9 at the head of the column. He had no 40mm ammunition left but we thought

that the tracked vehicle would be more effective in breaking through obstacles than

wheeled vehicles. All remaining artillery ammunition was expended and the guns were then

destroyed. Most of the available trucks belonged to the 57th Field Artillery and were

being driven by its men. Only the wounded who were unable to walk were loaded on the

trucks. We did not move out of the perimeter, however, until we received a specific

order from Maj. Gen. Oliver P. Smith over Capt. Ed Stamford's TAC radio. I was

standing next to the radio when the message came through. That order was received about

1 p.m.

After receiving Gen.

Smith's order the column moved out and quickly ran into a Chinese roadblock

constructed of logs placed across the road, covered by automatic weapons and small arms

fire. At the time four Corsairs were covering the inlet. Capt. Stamford instructed the

Corsairs to come down and knock out the roadblock which we marked for them. The first

Corsair came down the column, north to south, at tree‐top level. The pilot

dropped a napalm bomb which landed right on top of Sgt. Brown's M‐19.

Several members of the M‐19 crew, who were aflame, came off the mount screaming.

Some of the

napalm sprayed off of the M‐l9 to the left of the

road and hit some other soldiers. One of the M‐l9 crew members came directly

toward me, aflame. My first reaction was to shoot him (which I couldn't have done

as my carbine wouldn't fire). We threw him to the ground and tried to smother the

flames. We were able to put the flames out but he was mortally wounded. We then put him

on one of the trucks. In the meantime, the remaining Corsairs had neutralized the

roadblock. The M‐l9 was still running and Sgt. Brown somehow got it moving. The

napalm incident startled everyone. The troops in the immediate area became disorganized.

After some delay, the column started moving again.

The absence of men around this gun indicates the photo may have

been taken on 30 November, the day before the breakout. By that time casualties reduced

the crews available, and the shortage of ammunition reduced the need for manned

guns.‐‐ Photo courtesy Ivan Long, Hq/31/7

The absence of men around this gun indicates the photo may have

been taken on 30 November, the day before the breakout. By that time casualties reduced

the crews available, and the shortage of ammunition reduced the need for manned

guns.‐‐ Photo courtesy Ivan Long, Hq/31/7

Shortly before the truck column moved out, I

met Col. Faith for the first time. He was wearing ODs, a sheepskin vest, and was holding

a .45 automatic in his right hand. He ordered me to organize any available unassigned

troops for flank protection on the forward, left‐hand side of the column, which I

did. The column moved south until it came to the first bridge that had been destroyed

(map 11, p. 149). During that part of the trip, the column received small arms and

automatic weapons fire from the high ground on the left, the marshes on the right and

the road in front. We had some air cover. All of the aircraft were Corsairs (F4Us). The

only F7F that appeared over the area was at Hill 1221 much later in the day. It should

be emphasized that by this time there was no effective means of communication left. The

troops from various units had become so commingled that there was no unit integrity.

Consequently, there was no functioning chain of command and the column was moving of its

own volition.

This photo is on the way out. The men are from Company M,

3/31, and are part of the rear guard.

This was several miles south of the Inlet. The two men lying

in the foreground are dead. The road is just over the bank to the left, and the

trucks, at the time I took this photo, are about 100 yards behind me. A Chinese

foot column is less than 100 yards to the rear of the men pulling out.

Heavy enemy fire is coming from the hill, visible in the rear.

I estimate this photo was taken about 1530 hours." ‐Photo and

text courtesy William Donovan, L3/31

When the lead vehicles reached the

first knocked‐out bridge, and one of the trucks broke through the ice trying to

bypass the bridge, the column came to a halt. The troops on the left‐hand side of

the column fanned out toward several buildings in the valley. They got mixed in with

other soldiers. At that point, we were receiving heavy small arms and automatic weapons

fire both from the north side (Hill 1456) and the south side (Hill 1221) of the

streambed. We were taking heavy casualties. At this point, Lt. Tackus was critically

wounded. He was shot in the back of the neck by a small‐caliber bullet. While

trying to help him, I could see the bullet lodged near his cervical spine below the base

of his skull. He couldn't move.

HILL 1221

I knew that something had to

be done to neutralize the machine gun fire that was sweeping the road and bridge from

the crest of Hill 1221. About this time, a fairly large body of troops, about a

company‐sized unit, moved across the valley floor, in a southerly direction, and

disappeared from sight to the east of Hill 1221. Somebody said that it was A Company of

the 32nd Infantry. I moved up to the road on the side of Hill 1221. There were quite a

few soldiers huddled in a ditch between the road and the base of the hill. I tried to

cajole them, encourage them or do anything possible to get them going so we could attack

the Chinese on top of the hill. But most of them apparently had gone as far as they

could go. An infantry officer laying on the bottom of the hill was also trying to rally

the soldiers. He was badly wounded, but he urged the troops to move out even though he

was unable to get to his feet. At any rate, I did get a few volunteers, perhaps a squad,

and organized them for an assault on the hill. One of the men in the group was from

Capt. Stamford's TACP. He had lost his trigger finger mittens so I gave him my

scarf to wrap around his hands so they wouldn't freeze. He was killed later in the

day.

Frankly, I wasn't sure

that I'd ever make it to the top of the hill. I had not slept and had had almost

nothing to eat or drink since Nov. 29. Halfway up the hill, I discarded my field

overcoat because it was too heavy and restricting. After that, I was wearing a pile

liner as an outer garment. Every step forward was a struggle. A Chinese machine gunner

on top of the hill fired at me the entire time I was making my way up the hill. He

nicked me several times but I finally got close enough to finish him off with two hand

grenades. I had lost most of my makeshift squad on the way up the hill. My carbine was

still wouldn't fire. It was very late in the afternoon when we reached the top of

Hill 1221. Lt Eichorn led another small group of soldiers up to the top from the

northwest side of the hill. As soon as we entered the Chinese trenches, an air strike

came in and plastered us. We were worked over with rockets, machine gun fire and napalm.

There was one Grumman F7F in the group of four attacking aircraft. That was the only F7F

I saw that day. The air strike finished off most of the remaining soldiers.

Following the air strike there were no live Chinese left in

the immediate area of the crest of Hill 1221, which temporarily eliminated a problem for

the truck column. There was still enough daylight to see. I scanned the area through my

field glasses from this vantage point. Looking back toward the knocked‐out

bridge, I saw a company of what appeared to be North Korean soldiers traveling west,

parallel to the stream bed, along the base of Hill 1456. I thought that they were North

Koreans as they were dressed in grayish‐white uniforms. The top part of their

uniforms included fur‐lined hoods. Their uniforms were not the same as the olive

drab quilted uniforms the Chinese were wearing. They also looked larger than Chinese.

This group came up behind the truck column, moved along both sides of the trucks, poured

gasoline on the wounded men and set fire to them. It was not a very pleasant sight to

see. By then, a few of the trucks had bypassed the knocked‐out bridge and were

stopped along the road on the north side of Hill 1221. The truck column was no longer

being effectively defended as far as I could determine. It was obvious that the trucks

were not going to make it much farther. I could not observe any military activity taking

place to the east, west or south of Hill 1221. My view in those directions was blocked

to some extent by wooded areas and intermediate masks. Darkness fell.

After reviewing the situation for a while, I took a couple of men and

moved off into a southeasterly direction and Lt. Eichorn took a few men and moved in a

more southerly direction. The next time we met was in a hospital in Japan. Before

leaving the top of the hill, I took an M1 rifle that would fire and about ten rounds of

ammunition from a dead soldier. Shortly thereafter, I captured a Chinese soldier.

Although I don't speak Chinese, I told him we wanted to go to Hagaru‐ri. I

put my carbine bayonet in his ribs and he seemed to understand my message. We meandered

slowly down the hill and exchanged fire with several different small groups of Chinese

along the way. While descending the hill, I couldn't see or hear anything on the

east side of the hill. We finally got to the bottom of the hill just west of the second

blown bridge. We proceeded south to the area of Hudong‐ni and again exchanged

fire with several Chinese units. Around Hudong‐ni, we proceeded west and crossed

the ice, then moved south and entered the Marine position through a marshy area. While

crossing the ice we received rifle and automatic weapons fire from the Chinese on the

shore. Luckily, most of the their fire was well over our heads.

As we made our way south through the marshy area, I was suddenly

challenged by a Marine sentry. I had a short discussion with him while he satisfied

himself as to our identity. There were still four of us, including the prisoner. It was

just before daybreak on 12/2. The Marine came out and led us safely through the

minefield. The Marines then took charge of the prisoner and the rest of us were taken to

an aid station. Late in the afternoon of 12/2, I was air‐evacuated from

Hagaru‐ri aboard a Royal Hellenic Air Force C‐47. As the plane lifted off

of the airstrip, Chinese machine gunners at the end of the strip were firing at it. The

starboard wing was hit several times. That aircraft was later identified as belonging to

Flight 13 of the Greek Air Force which was attached to a squadron of the USAF. I have

never seen anything written about the operation that mentioned any Greek military

personnel in the area.) The plane landed near Hungnam. I was first taken to the hospital

ship, USS Consolation, then evacuated to the 172nd Army Hospital in Japan and later

transferred to the 155th Station Hospital in Japan.

Personal reports of battles have had

varying recall of when the message from Gen. Smith was received by LTC Faith. Roy

Appleman reported in Escaping the Trap (p.139), "About 3 pm ... Major Curtis said

that the artillery observer's jeep‐mounted radio picked up the following

message in the clear: 'To Colonel Faith: Secure your own exit to Hagaru‐ri.

Unable to assist you. Signed Smith, CG 1st Marine Division.' "

In his manuscript of January 1953 Maj.

Curtis did not mention receipt of a message at the beginning of the breakout, although

he did report "Col. Faith, upon consultation with his staff, decided to try to

break out of the perimeter and reach Hagaru‐ri in a single dash rather than risk

another night in the perimeter."

We searched an additional source, the

forward air controller, Edward P. Stamford. He said: "At daylight [1 December] Col.

Faith made preparations to fight south to Hagaru‐ri and had me send a message

requesting aircraft and to notify CG, 7th Inf. Div. of his contemplated action."

Note that Stamford did not mention Gen. Smith, indicating he did not know they were

attached to the 1st Marine Division.

Stamford last mentioned

contact with air when units attacked Hill 1221. "At this time I was on the road

about at the foot of [the hill] and had been running strikes on [Hill 1221] and all the

high ground north and northeast thereof. I had extreme difficulty at this time in

running missions because the troops were now assaulting Hill 1221 on the south and the

pilots of the aircraft were cluttering up the air with their own transmissions. Some

strafing missions were run immediately to my front and on the stoop side of the hill

below the road where enemy troops were trying to attack the rear of troops assaulting

the hill." Many survivors of that action have reported friendly fire casualties

from strafing and napalm.

It has been obvious to historians and students

of Chosin that the battle for Hill 1221 sounded the final bugle call for Faith's

attempt to do the impossible. The climax came as darkness began to reduce visibility and

prevent further air support. Here we close this report with two pilots remembering the

last moments. They are Marine pilots Ed Montagne and Tom Mulvihill who were flying their

Corsairs on an urgent mission to drop ammunition to the units fighting Hill

1221.

Montagne: "We circled the reservoir for a while trying to reach

Boyhood One‐Four [Ed Stamford] to get permission to make the drop, to no avail.

Much yelling into [the] microphone. I do believe Tom [Mulvihill] tried to get Boyhood

One‐Four to calm down. . . So we finally went out over the reservoir, dropped

down to almost water [ice] level, slowed up to about 100 knots and went in right over

the truck convoy to make the drop. Just as we were about to reach the trucks, someone (I

presume Stamford) yelled into the mike "You're strafing us," or words to

that effect. We could see the troops huddled around the vehicles and up the side of the

hill, their black forms against the snow. . . As I remember, Tom and I were shaken by

their situation and there was some discussion about sending more planes to help hem...In

fact I felt bad that we were not able to do more to help them. To this day I don't

know if they ever recovered the ammo. Did it do them any good? Were we any help in our

rocket and strafing runs?"

Tom Mulvihill "... we dropped small arms ammunition

to them the last night they were in business, and we hung around until after dark

strafing and trying our best to keep the Chinese from them. But it was all over, there

was no doubt about it."

END CJ 12.15.02

==========

|