CHANGJIN JOURNAL 11.01.01 (Part I)

The Changjin

Journal is designed to disseminate and solicit information on the Chosin

campaign. Comments and brief essays are invited. Subject matter will be

limited to history of the Chosin campaign, as well as past or present

interpretation of that history. See End Notes for distribution and other

notices. Colonel George A. Rasula, USA‐Ret, Chosin Historian Byron

Sims, Contributing Editor

IN THIS ISSUE We have been

working for some time on our review/critique of newly published biography of

General O. P. Smith: The Gentle Warrior: General Oliver Prince Smith, USMC,

by Clifton La Bree, Kent State University Press, 2001. This has been an

interesting task because our critique relates to interpretations of the

Chosin campaign by the author and his references to the writings of General

Smith and others. It should not to be read as personal criticism of the late

general. As students of the Chosin story will understand, critical topics

relate to command of army units attached to the 1st Marine Division. Readers

are encouraged to familiarize themselves with these past issues of the

Changjin Journal: CJ04.05.00, CJ04.28.00, CJ05.06.00 and

CJ01.22.01.

THE GENTLE WARRIOR This book is rather

limited in the personal background and details about Oliver Prince Smith who

began his life on a Texas ranch in 1893, lost a father at age six after

which he was taken to the coast of California where he later entered the

university at Berkeley. His claim to fame would eventually be Inchon/Seoul

and Chosin campaigns of the Korean War.

General Smith was

a gentleman scholar who, as a young man with four years of French in school,

enjoyed two years at France's war college – the Ecole de Guerre.

This without doubt set him up as a thinker and planner who went on to

important assignments in World War II: regimental commander in the New

Britain campaign; assistant division commander of the 1st Marine Division on

Peleliu, and deputy chief of staff, Headquarters Tenth Army, on Okinawa.

This culminated in his Korean War assignment as commanding general of the

1st Marine Division from Camp Pendleton to April 1951.

The calm person that he turned out to be was probably due to losing a father

at age six and being brought up by a resourceful mother in a home where hard

work was the cornerstone to success. Some readers regret there is nothing

about his youth, nor details of his time in school at Berkeley.

Although Smith's military education received a

kick‐start in army ROTC, the foundation was probably laid at Fort

Benning's Infantry School where he associated with many future greats

such as George C. Marshall, Omar Bradley, "Vinegar Joe" Stillwell,

Bedell Smith, et al. It was at the Infantry School during his

ten‐month course in 1931 where the future leaders of the next world

war were visualizing the battlefield, providing excellent background for

Smith's two‐year tour at the French Ecole de Guerre during

1934‐36. With Hitler emerging with his plan of world conquest,

Smith's training as an officer was off to a good start.

The author briefly sketches Smith's experience in World War

II, then to the Korean War in more detail, followed by post‐Korea in

which he provides his explanation of Smith's handling of the

Presidential Unit Citation (PUC).

INTERSERVICE RIVALRY

The World War II chapters reveal origins of interservice rivalry that

reached a peak during the Korean War and continued to thereafter. Most

Chosin veterans familiar with "Smith vs. Almond" may not know of

"Smith vs. Smith" that occurred on Saipan where marine general

Holland Smith relieved army general Ralph Smith who was commander of the

27th Infantry Division and happened to be a classmate of O.P. Smith at the

Ecole de Guerre. As stated by the author, this "led to a rift between

the army and the marines, one that lingers to this day." Although there

were no direct command contacts between MacArthur and Smith, we did learn

"when asked what the marines had against General MacArthur," Smith

said "I told him frankly that our unfavorable opinion of him was

compounded by several things, some important and some minor; that we

appreciated his ability but did not like him."

THE

LINK Although the reorganization of the services in 1947 may have been the

start point of the problem, our study links it with "Smith vs.

Smith" on Saipan, "Smith vs. MacArthur" and "Smith vs.

Almond," all having been mentioned by historians of the Korean War. One

may ask if this linkage caused this gentle warrior to handle the army units

attached to him during Chosin as he did, and was it interservice rivalry

that caused him to dishonor the units of RCT 31 by not including them in his

list to receive the PUC? Or was the reason purely "Smith vs.

Almond"? This book may provide indicators, but it does not answer the

question.

POST‐KOREA The author uses two chapters

to cover Chosin, North to the Chosin and Disaster at the Chosin. Later in

post‐Korea, he addresses Smith's handling of the PUC problem. As

a general comment, we find the handling of Chosin and the PUC not only

confusing, but often inaccurate in the selection and use of

resources.

END NOTES Part II of this Changjin Journal

covering the Chosin campaign and PUC problem is being published separately

on the web pages of the New York Military Affairs Symposium

http://nymas.org/

END CJ 11.01.01 (Part I) CHANGJIN

JOURNAL 11.01.01 (Part II)

THIS ISSUE is Part II of

the review The Gentle Warrior: General Oliver Prince Smith, USMC, by

Clifton La Bree, Kent State University Press, 2001, presented as a

critique of those portions of the book related to the Chosin campaign

and award of the Presidential Unit Citation. To avoid reading quotations

out of context, it is suggested that these comments be used as a

companion to reading the book. Another excellent source is Roy

Appleman's Escaping the Trap, published by Texas A&M University

Press. See Part I for related issues of the Changjin Journal.

Chapter 9: NORTH TO THE CHOSIN

p.145 The

author uses many extracts from Smith's aide‐memoire both out

of context and out of sequence with what happened, which causes

confusion. "Almond ordered Smith, during a visit to his divisional

CP on 14 November, to attack to the west in support of Eighth army, and

he allowed Barr's 7th Division to continue toward the Yalu, where

he could not support Eighth Army." Almond did not order Smith to

attack west during his visit on 14 November. The author is citing Toland

273 wherein FEC on 15 November ordered Almond to "reorient his

attack." After this planners at 10th Corps went to work developing

a plan to enable the 1MarDiv to turn west. In his zone of operations,

Barr "could not support Eighth Army" because the terrain

prohibited westward movement of the 7th Division. To relieve the 5th

Marines east of the reservoir, the boundary between 1MarDiv and 7th

Division was moved west to give the zone east of the reservoir to RCT

31.

pp. 145‐50 The author provides

Smith's complete letter of 15 November to the commandant of the

corps, describing it as a "remarkable letter [showing] that Smith

and his staff took the Chinese threat seriously and were actually making

preparations on that assumption." Barr, an old China hand, was

equally concerned with the Chinese threat to his west, causing him to

block the sector vacated by RCT 31.

p.151

"Almond ordered Smith to move RCT 5 to the east side of the Chosin

reservoir en route to the border on 23 November" after which he

"directed Litzenberg to occupy for the time being a suitable

blocking position west of Hagaru‐ri and not over the mountain

[Toktong] pass. I hoped there might be some change in the orders on the

conservative side. This change did not materialize and I had to direct

Litzenberg to go on to Yudam‐ni." One may ask why the 7th

Marines was sent to Yudam‐ni when the best defensive position was

the Toktong Pass?

p.152 "A patrol of

3/5 Marines was sent north to determine enemy strength and the condition

of the Chosin Dam, between the Fusen reservoir and the Chosin

reservoir." We continue to find errors in interpretation of the

aide‐memoire references. In this case the actual mission of the

patrol was to "determine presence of the enemy in the area and of

observing [enemy] activity at the dam." A platoon‐size

patrol with two noisy tanks could hardly perform recon of the enemy; it

was limited to road recon at best. As for observing "activity at

the dam," Smith reports the battalion commander made a helicopter

recon and "reported no indication of enemy activity in the

area."

"Almond ordered the 7th Division to

provide whatever units it had available to relieve RCT 5 on the eastern

side of the reservoir. This would...transfer the mission of protecting

the right or east flank of this attack to another force...."

Whatever units it had available is hardly a description of a mission

assigned to 7th Division. Relief does not automatically "transfer a

mission of protecting the right or east flank of this attack to another

force–a new regimental task force from the 7th Division." A

relief order would have to include such a mission statement: it

didn't. The author is misreading a source [n.16 cites Appleman EC,

p.5] that does not exist.

p.153 "The 7th Marines

had been in continuous and heavy combat since landing at Wonsan, so

Smith ordered it to hold while the 5th led the advance." The 7th

Marines heavy combat had been at Sudong‐ni about 6 November,

after which it observed occasional enemy patrols until the major CCF

attack the night of 27 November.

p.153 "The

Eleventh Marines [artillery units] had been parceled out to the infantry

regiments." Due to the dispersion of major units, the direct

support battalions of the 11th Marines were attached to the regiments,

making them regimental combat teams in the same manner as in army

regiments.

"Aircraft were reporting alarming

numbers of enemy soldier to the southwest, west and northwest of

Hagaru‐ri. Civilians were reporting similar sightings. The

fighting on most of the front was sporadic, but almost constant contact

was maintained with Chinese forces."

The author

creates a sense of urgency which did not exist at the time. Contact with

Chinese was limited to individuals and small patrols, not "alarming

numbers" or "forces." The Chinese had intelligence

patrols working all along the Chosin MSR watching the marines, reporting

their findings which provided the basis for attack plans.

p.154 Task Force Drysdale. "Captain Peckham was ordered

by Puller to lead the convoy to Hagaru‐ri." Lt. Colonel

Drysdale was in command and the lead unit out of Koto‐ri was the

41 Commando. Smith at Hagaru‐ri did not have direct contact with

Drysdale; orders went through Puller at Koto‐ri who had the

responsibility for coordinating the operation.

p.155‐56 "The situation of the 1MarDiv and its attached

units on the evening of 29 November was as follows...north of

Hagaru‐ri, on the east side of the reservoir, over 2,500 army

troops from the RCT 31 had faced an overwhelming Chinese attack, and

their fate was still unknown...." There was far more information

available about the situation east of the reservoir than indicated by

the author. The forward air controller with Faith's 1/32 Infantry

was in daily contact with supporting aircraft. On the evening of 29

November Faith's battalion had already joined the perimeter of 3/31

Infantry where Faith had assumed command of RCT 31units at the Inlet.

Tank Company /31 had on 29 November made a second unsuccessful attempt

to break through from Hudong‐ni. All of these facts were known at

Hagaru‐ri. It was the evening of 29 November when all army units

in the Chosin area were attached (not operational control) to

Smith's 1MarDiv, a time when Smith knew he now had a fourth RCT

under his command.

Chapter 10: DISASTER AT THE

CHOSIN

p.158 "The day before the meeting in

Tokyo, Almond visited the 31st RCT's forward headquarters, where he

gave orders to continue the advance...Then he ordered Colonel Faith to

continue the attack northward. Almond refused to understand the reality

of what was happening to his command; his orders bordered on tactical

incompetence. His disregard for his men sealed the fate of Col. Allan D.

MacLean's 31st RCT, on the eastern side of the Chosin

Resevoir." [cites Stanton 231 and Blair 521] These are powerful

accusations that have questionable support. Stanton's reference is

found on p. 232: "It is apparent that Almond did not understand the

reality of the Changjin disaster..." which in turn cites Appleman

EC p.170: "Almond's unrealistic belief that he could continue

his attack is hard to explain" and "He had badly misjudged the

situation." These citations are in relation to the conference with

Gen. MacArthur when far more information was available about the enemy.

Authors tend to search for a dark side of Almond, yet none have

explained why Almond continued as a corps commander under Gen. Ridgeway

in 1951. By the time of the Tokyo conference, situation reports finally

convinced MacArthur that further attack was out of the question.

Almond's tendency to adhere strictly to MacArthur's orders was

a problem. Authors seem to seek fault with Almond's statements,

mostly based on hearsay rather than on what he had ordered. He did not

order Faith to attack. What he said was "we are going to continue

the attack, don't let the laundrymen stop you ...", with

"we" taken as an order to attack. It wasn't. The reader

must keep in mind that details of the Silver Star incident were based on

interviews with few soldiers who reported what they thought they heard

at the time; not from Faith or MacLean who were dead. Bear in mind also

that MacLean had no intention of attacking until the arrival of his

third infantry battalion (2/31). At the time of the incident, MacLean

was in command, not Faith. We have found interesting differences in

coverage of Almond's visit to Faith on 28 November, a topic we may

address in future journals.

"RCT 31 was hit hard

the night of 27‐28 November. The Chinese had been reinforced by

one or two armored vehicles, which overran the artillery positions in

the Sinhung‐ni area and to the north, inflicting heavy casualties

on the army units." There were no enemy armored vehicles of any

kind attacking or overrunning the artillery at the Sinhung‐ni

perimeter area (3/31 Inf. and 57FA Bn).

p.162

"(Colonel MacLean was killed on 28 November, and the unit has been

called 'Task Force Faith' every since.)" MacLean was

wounded and carried off by the Chinese the morning of 29 November during

the 1/32 withdrawal. Faith became RCT commander at the Inlet when he

learned that both Reilly and Embree had been seriously wounded.

p.162 "On 30 November, BGen Hodes...established an

advance CP a few miles north of Hagaru‐ri..." Hodes was

present at the RCT 31 CP at Hudong‐ni the night of 27‐28

November, took part in the Tank Company attack on Hill 1221 on 28

November, and returned to Hagaru‐ri in a tank on the afternoon of

28 November, never to return to Hudong‐ni. No historian or critic

of Chosin has yet addressed Smith's reported guidance to Faith to

"do nothing that would jeopardize the safety of the wounded'

(A‐M 896‐97), a message that did not arrive until the

attack was well under way. To place hundreds of wounded men on trucks

and transport them through enemy resistance can be seen to violate the

order of not jeopardizing their safety. Smith and others apparently had

no idea what the situation was at the Inlet, nor did they do anything to

find out. Responsibility for communications is from the top down, not

from Faith to Smith.

p.164 "In the meantime, a

new task force was being organized around [LTC] Anderson, senior army

officer in the Hagaru‐ri perimeter. (It should be noted that some

veterans of RCT 31 dispute whether the following action actually took

place, but it is mentioned in three very reliable sources.)" Within

this critique we mention three reliable living sources who were present

at the time on the perimeter road east of the reservoir.

"The force was the equivalent of a rifle company,

reinforced by tanks and air support. Anderson planned to jump off

between 0930 and 1100 on 2 December and reach out to assist Task Force

Faith into Hagaru‐ri. The force was reduced at the last minute to

only two platoons of tanks, but it jumped off as planned...[and] ordered

not to become so heavily engaged that it might be cut off." The

force as described was planned in the command tent of Anderson who at

the time was also involved in planning the organization of army units

for the breakout. Capt. Rasula (assistant S‐3) and Lt. Escue

(S‐3 liaison officer) were present on 1 December, then sent to

the north perimeter (H/11 Artillery positions) to assist in the passage

by RCT 31 troops coming from the north. "After reaching a point

about 4,000 yards north of Hagaru‐ri, the task force came under

heavy attack from the flanks and rear and the tail of the column was

momentarily cut off. After picking up some 10 ...wounded in the vicinity

of the road block, Task Force Anderson was ordered to return to

Hagaru‐ri. The column turned around and successfully reached the

perimeter of Hagaru‐ri." [Author cites Bowser and Smith.]

Although this force was planned, it was neither organized nor did it

engage in the action described. Remember that Faith's command did

not exist after daylight on 2 December. All that remained were

individuals and small groups attempting to make their way south over the

ice of the reservoir or overland. These facts were known at

Hagaru‐ri. The only activity on the east road on 2 December was

the rescue of wounded by Escue (mentioned by the author two paragraphs

later in discussion about Beall's efforts), witnessed by Rasula and

others. There were no wounded at the roadblock and those found north of

the block were picked up by Escue. There was no enemy action nor enemy

sighted in the immediate vicinity of the roadblock. Col. Robert E.

Drake, USA (Ret.) who commanded Tank/31, states emphatically that Task

Force Anderson did not take place; noting that some historians may be

confused with the action on 3 December by 41 Commando and a platoon of

tanks from 31st Tank Company that went a short distance toward Toktong

Pass, engaged in a minor action and had to turn around because it was

too late in the day [p.172]. Rasula and Escue were both in the vicinity

of the roadblock during 1‐3 December and witness to the fact that

Task Force Anderson did not take place. This is an example of how past

historians and writers differ in use of research, some relying on

written sources while others going further through interviews with

Chosin veterans. Both Appleman and Blair were conducting research before

the Chosin Few was formed, an organization which brought forth many more

survivors of the Chosin campaign. This is one example of incorrect

journal entries. To write that "three reliable [written]

sources" are more reliable than the sworn statements of three

eyewitnesses does not serve history and insults the integrity of the

three officers making the statements. Other errors in this part of the

book deal with misinterpretation of past writings, such as "in the

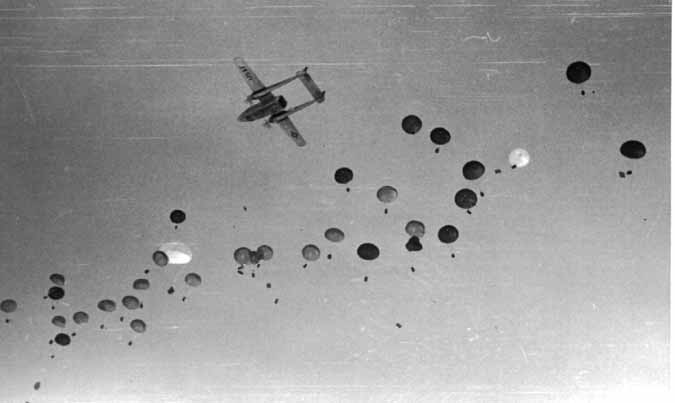

first few days of December, 250 tons were dropped to the remaining

survivors by the...Cargo Command." No drops were made on or after 1

December.

p.165 "During the forty‐five

years since Smith wrote his Korean narrative, more information has

become available regarding the performance and fate of the RCT 31...The

loss of all records and most of the officers and noncoms had contributed

to a lack of appreciation for the contribution that the unit

made...certain facts should be pointed out, because they directly relate

to O.P. Smith's performance as commanding general...."

"When Smith assembled what he called his

'aide‐memoire,' he was not aware of the significant

role played by the army units east of Chosin. As a matter of a fact, he

was probably influenced by Colonel Beall...who had been responsible for

the rescue of hundreds of survivors from RCT 31. Ironically, in 1953

Colonel Beall submitted a scathing report against the army in the Chosin

campaign, which calls to question his powers of observation and his

integrity..."It is now clear that RCT 31's actions spared the

1st Marine Division the heavy casualties that the Chinese would have

inflicted if the army units had not delayed their attack. It is possible

that RCT 31 saved the division from destruction." Further research

by the author would have revealed that the army units east of Chosin did

play a significant role. He would have found the 1951 investigation by

the Inspector General of X Corps which reported RCT 31 had been attacked

by two CCF divisions; a letter from Ridgeway to the Secretary of the

Army reporting RCT 31 "withstood repeated attacks by more than two

CCF divisions of more than 20,000 before being overwhelmed by a

numerically superior enemy."; and a 1964 statement by historian

David Rees, Korea: The Limited War, p.164, "These terrible losses

had to be placed against the saving of Hagaru itself, and with it the

Marine Division."

p.167 "Could Smith have

done more to assist the survivors? At the time, his command was in

danger of being overrun; his staff was not functioning at its normal

capacity...; his assistant division commander was away on emergency

leave; and he had just become responsible for the extraction of the army

units east of Chosin, even though he had never had any input about their

mission, which had got them into their desperate situation in the first

place." The author asks an important question –"could

Smith have done more"–and then follows with what appears to

be a series of excuses rather than an answer. No staff functions in a

"normal capacity" in combat. In this case no staff member at

Hagaru‐ri had been killed or wounded. The perimeters of

Koto‐ri and Chinhung‐ni required very little attention

from the division staff. Smith allowed Craig to leave. Had he been

wounded or killed, Smith would have appointed an acting ADC and sent a

message to the commandant urgently requesting a replacement. He

didn't fill the vacant position with a senior colonel. Stating that

he "never had any input about their [RCT 31] mission" causes

one to question the performance of a commander. When one becomes

responsible for a newly attached unit he must establish communications

with the commander of that unit either personally or through his staff,

primarily is G‐3. This is a normal function in combat, not a

reason why a commander could not "have done more." The mission

of RCT 31 was as well known to Smith as it was to Barr and

Almond.

Readers of The Gentle Warrior should remember

that Smith's aide‐memoire was not written at the time of the

Chosin campaign, but later. He appears to have used only one source

about RCT 31 east of the reservoir, a report by the forward air

controller with 1/32, further influenced by Beall's report about

helping survivors, both submitted after the Chosin campaign. Neither

Smith nor historians of the Marine Corps interviewed army survivors of

RCT 31 to help form an accurate basis for the official history of the

Chosin campaign.

p.169 "On 28 November Smith had

no knowledge of Tenth Corps's plans for the situation."

Response to this statement can be found in Blair, p.462, describing

Almond's visit with Smith and concludes "After he [Almond] had

departed, Smith issued orders officially canceling the Marine Corps

offensive."

"The evening of 28‐29

November brought division‐sized attacks against the defenders of

Hagaru‐ri and Koto‐ri." There were no

"division‐sized" attacks against any of the formations

at Chosin, certainly not at Hagaru‐ri or Koto‐ri. The

Chinese weren't capable of controlling attacks of such magnitude.

Bugles, flares and other signal devices were the only means they had of

controlling a few hundred soldiers. Once an attack was under way, they

couldn't change their plans.

"The attacks

against Hagaru‐ri and Koto‐ri continued, with heavy losses

to the enemy, mainly from marine air support." There were no major

attacks on Koto‐ri during the entire campaign. Attacks against

Hagaru‐ri were defended mainly by perimeter units supported by

mortars and artillery. Air support was not a factor in defending against

the night attacks.

"To the slender infantry

garrison of Hagaru‐ri were added a tank company (army) of about

100 men and some 300 seasoned infantrymen," referring to

"(A‐M, 868)." The tanks from Task Force Drysdale were

marine. The army tank company was at Hudong‐ni.

"Generals Hodes, Barr, and Almond all descended on the CP

to discuss the Task Force Faith situation with Smith." The

discussion was about the 1MarDiv situation at a time when RCT 31 was

holding back two CCF divisions that threatened the security of

Hagaru‐ri. Smith's RCT 5 and RCT 7 were being threatened at

Yudam‐ni.

Chapter 12: POST KOREA THE

PRESIDENTIAL UNIT CITATION (PUC)

p.212 "On 3

March 1952, Smith wrote a long letter to Lemuel C. Shepherd, the new

commandant of the Marine Corps, recommending that the 1MarDiv and its

attached units be awarded the PUC for their actions at the Chosin

reservoir." The source of the PUC did not originate with

Smith's letter to the commandant; it originated with his successor,

Maj. Gen. Thomas, who recommended two of his battalions for the

Distinguished Unit Citation (DUC).

p.213 "Smith

was not briefed by Almond or any other staff officer in regard to the

31st RCT, except perhaps when Generals Almond, Barr, and Hodes were at

Hagaru‐ri after responsibility for the RCT had been passed to the

1MarDiv." Smith would have asked his staff, specifically his

G‐3, to brief him on an attached organization, especially a

regimental combat team. To say Smith didn't know the obvious is

contrary to describing him as an intelligent and considerate person, a

gentle warrior.

"We know now that the 31st RCT

actions probably insured that the 5th and 7th Marines successfully reach

Hagaru‐ri. However, Smith did not have that information available

to him; trying to be as fair as his standard would allow, he substituted

the disputed 'Provisional Battalion...’ for the 31st RCT. By

Smith's standard, objectively and unemotionally applied, he was

correct in limiting the citation to the provisional battalion, because

it was this unit that he saw make a direct contribution to the

breakout." That Smith "saw [them] make a direct

contribution" applies no more to the provisional battalion than to

the RCT units east of the reservoir; in either case he did not

personally observe the performance of any army unit. To say Smith

"did not have that information available" at the time of the

battle is saying he did not do his job of keeping himself informed of

the status of units under his command. Considerations and decisions

involved in writing his eleventh endorsement were based on his knowledge

at the time he signed the document, not what he knew during the

battle.

"Some veterans of the 31st RCT claim

that additional information about the performance of the 31st RCT was

provided to Secretary of the Army...on 31 May 1951 by General Ridgeway;

'the 31st RCT withstood repeated attacks of more than two CCF

divisions of over 20,000 before being overwhelmed by a numerically

superior enemy.' It is unlikely Smith was aware of this somewhat

privileged information."

On 16 June 1951 the

Defense Department made public the reply of General Ridgeway to charges

[of cowardess and incompetence] made against the army in Korea by

Chaplain Otto W. Sporrer. On 16 June 1951 this statement appeared in

ARMY TIMES: "The Army said the facts showed that the 31st RCT had

about 2800 men and beat off repeated thrusts by more than 20,000 Reds

between Nov. 28 and Dec 1 before being overwhelmed by sheer force of

numbers." The ARMY TIMES story included: "The Navy has no

comment on Gen. Ridgeway's letter which referred to remarks in an

anonymous article in the West Coast magazine 'Fortnight.' The

statements were later attributed to Sporrer. Gen. Ridgeway said

'sufficient evidence has been obtained to conclude that the

allegations in general are without basis in fact." Under the

circumstances, it is difficult to believe that Smith knew nothing of

this report at the time.

p.214 "If some official

in the army chain of command was aware of the performance of the 31st

RCT, why did not that person take a stand in support of the traumatized

survivors of RCT 31 when the PUC endorsements were being

circulated?" It is obvious the author has little knowledge of the

chain of correspondence that led to the final PUC approval. Within that

chain are endorsements of commanders from the 7th Division, X Corps and

8th Army, as well as the weight of Gen. Mark Clark, CINC FECOM, and Vice

Adm. R.P. Briscoe, CONNAVFE, recommending the RCT 31 units that fought

east of Chosin and others. This is followed by the 11th Endorsement in

which Smith deleted the army units that fought east of Chosin. The

reason the board accepted Smith's list and not that of the chain of

command, including the Army Chief of Military History, has never been

made known. The question "why did not that person take a

stand" opens another door. The circulation of military

correspondence is limited to military staff addressing the subject and

not the public, and those who read the documents up the chain of command

to Washington saw favorable recommendations. There was no reason to

"take a stand." The change came from behind the scenes in the

Marine Corps‐Navy staff. There was no public knowledge of the

results until the document was signed and orders published.

"Those individuals who were deprived of its recognition

are justified in feeling forgotten and bitter, but their anger should

not be focused on General Smith. He as a fair and compassionate leader

who went out of his way to avoid controversy, and when he dealt with

other services he was respectful, fair, and truthful. That is a matter

of record." The PUC problem has as its background the conflict

between Smith and Almond. Smith was an educated officer who apparently

spent a lot of time thinking and writing his diary and later his

aide‐memoire. Did he wash his hands with the Sporrer incident by

leaving the problem with the Navy? In Smith's "Log" of 4

April 1951 we read "Colonel Martin, the assistant IG of GHQ [FEC]

was here to take testimony regarding the allegations contained in the

Sporrer letter. I talked to Martin a good bit off the record. I pointed

out to him that I could not see why I should be used to help prosecute

Sporrer; that what he had done was a matter between him and the Navy

Department." Was Smith's handling of Sporrer incident similar

to his handling of the PUC for RCT 31?

END NOTES

It's difficult to understand how a division commander could ignore

an attached infantry regiment, and then after the regiment is destroyed

by the enemy while part of his command, not ask "what happened and

why?" Maybe he did, but like a witness to an accident, didn't

wish to be involved. Why didn't he personally meet and talk with

the surviving senior army officers to find out what happened to MacLean?

The search for truth continues. Send comments to: grasula@nymas.org

END CJ 11.01.01 (Part II)

For past issues of the Changjin

Journal go to the Changjin Journal

Table of Contents

The new e‐mail address for

the Changjin Journal is <grasula@nymas.org>

Return to the New York

Military Affairs Symposium start page Return to the New York

Military Affairs Symposium start page

|