Full‐text of articles by

NYMAS Members

German and English Propaganda

in World War I

A paper given to NYMAS on December 1, 2000 by

Jonathan A. Epstein

CUNY

Graduate Center /NYMAS

1. Introduction

An analysis of British and German propaganda aimed at Americans during World War One reveals four main trends: blaming the other for the war, claims that America’s interests were antithetical to those of the enemy, exposure of the enemy’s atrocities, and claims of cultural or racial solidarity with America.

The Great War has been labeled the first modern propaganda war or "the first press agents' war." This was particularly true in the United States, which, as a major industrial power, was a rich prize for propagandists and which was where compulsory education led to a literate public which was ripe for the messages, which could now be transmitted by cable or wireless, of the two warring sides.

In a chilling omen of what was to come, the German advocates painted the conflict as a war between the Teutons or "White Race" against Slavic or "Asiatic" barbarism. Russians were condemned as "Kossacks" [sic],"half‐cultured Tartars," and "Asiatics," while the British and French were excoriated for using "colored savage troops" and encouraging Japanese intervention and conquest of German territories "without troubling about the consequences to the universal progress of the white race." Indeed, the German‐born Harvard psychiatrist and leading pro‐German propagandist Dr. Hugo Münsterberg painted a picture of a (presumably dystopian ) future in which Britain and her colonies are conquered by the Russians and the United States is destroyed by a Japanese‐Chinese‐(Asian)‐Indian alliance.

For their part, the British simplified the messiness of the conflict by blaming Germany for the crimes of its allies as well as itself. Thomas Masaryk argued that Emperor‐King Franz Josef, by giving Germany effective control over the Imperial and Royal Army to Germany, had ceded sovereignty to Germany while Arnold J. Toynbee, the eminent historian, placed the ultimate responsibility for the genocide of the Armenians on German shoulders for not stopping the Turks. Lewis Namier, another noted historian, went so far as to blame the least savory aspects of Russia, such as the pogroms, on the Germans resident in Russia. However, pro‐British propagandists generally made a distinction (repudiated by pro‐German propagandists) between German militarism, which Britain was fighting, and ordinary Germans, or German culture, which it was not.

All of these ideas were expressed in many media. There were films and radio broadcasts, as well as many permutations of printing—books, pamphlets, reprints of speeches, periodicals, and cartoons—all designed to influence American public opinion and to convince it of the British or German view of the world, the war, Europe’s best interest, and America’s best interest. In this study, I use exclusively printed media consisting of official, quasi‐official, or unofficial productions by authors from the warring nations or neutrals (the latter were highly desirable for the veneer of objectivity they provided), written before America’s entrance into the conflict and aimed at American readers. In the end, the British were more successful, as evidenced by our entry into the war on their side. However, it was not an even fight. The British benefited from several advantages over the Germans: a common language facilitated the disbursal of information, a common culture meant British propagandists did not have to demonstrate cultural affinity, a direct cable contact (the first British offensive move was to cut the cable running between Germany and America), and thus, more available means of communication.

2. German Propaganda Machinery

The Germans were first off the mark with the creation of propaganda machinery upon the outbreak of war and they had a hard job ahead of them; a November 1914 poll of 367 American newspaper editors revealed that, of those who expressed a preference, 105 preferred the Allies, while only 20 supported the Germans. Germany’s first propaganda action in the US was to establish the German Information Bureau.

Another early move was the foundation of the Zentralstelle für Auslandsdienst (Central

Office for Foreign Services) by Matthias Erzberger (a leader of the Catholic Center Party and

member of the Reichstag [German parliament] and eventually a signer of the 1918

Armistice, and who would be assassinated for this last deed) by decree of the Imperial

Chancellor Betthman‐Hollweg. It was funded by the Foreign Affairs Department of the

German Government. It dealt mainly with printed matter, collecting and studying works from all

perspectives for its own information. However, its main task was to distribute German material

abroad—purchasing likely propaganda material from publishers and encouraging or

commissioning propaganda works. The majority of this material was pamphlets, books, official

documents, speeches and even anthologies of "war poetry," fiction, and

children’s books. All types were usually by Germans and were originally written in German.

A minority was periodical, especially The Continental Times which ran to 15,000 copies in

1916; the monthly Kriegs‐Chronik (War Chronicle), 12,000 copies of which

were printed in English, and Der große Krieg im Bildern (The Great War in

Pictures), with each photograph captioned in up to six languages, including English; and

the weekly Illustrierter Kriegs‐Kurier (Illustrated War‐Courier).

The distribution of photographs was considered especially important and a "photo centre" [sic] was established, becoming the Filmed Photo Office" in 1917 to consolidate and coordinate visual propaganda. Photographs were emphasized because they did not need translation and could touch the emotions of the viewer. Much German propaganda showed the war from the German perspective although eliminating any negative aspects [See Appendix 1]. The following description of fighting in the Argonne is typical of items in the War Chronicle:

"We soon brought superior means of attack to bear on the French, and as our troops were unrivaled in perseverance, tenacity, and spirit of attack, a strong feeling of superiority pervaded them during these wood‐fights regarding the enemy. . . . They could not resist our attacks so that our troops were able to proceed slowly but continuously."

The Germans recognized the importance of winning American opinion. However, German propaganda was hamstrung by an inability among the leaders to understand propaganda techniques. Indeed, the German Ambassador to Washington, and a leading German propagandist in his own right, Count Johann Heinrich von Bernstorff, recognized that German propaganda in America suffered from a misunderstanding of the American character:

"He is not interested in learning the ‘truth,’ which the German press news and written clarifications tried to bring across to him. The American wants to come to his own judgment and, therefore, wants facts only. . . . [The works were] written in a manner which was almost always legally precise, propagandistic but completely misguided."

German propaganda was also generally reactive. It spent much energy defending Germany against Entente charges of crimes against persons, both civilian and military, and cultural monuments. The German military leadership gave the propagandists much to defend; the latter had to deal with the invasion of Belgium and unrestricted submarine warfare, especially defending the sinking of the Lusitania.

3. German Propagandists

As noted above, the German Ambassador to Washington, Count von Bernstorff (1862‐1939), later to become a Reichstag member and then anti‐Nazi exile, was one of the main German propagandists in America. Among his colleagues were the German‐American journalist George S. Viereck; a Dr. Karl A. Fuehr; the ill‐fated Dr. Heinrich Albert of the German Department of the Interior; Professor Münsterberg, who tried to nurture a pro‐German sympathy in Theodore Roosevelt and threatened President Wilson with an electoral backlash on the part of pro‐German ethnic groups in America should he persist in his pro‐Entente bias; and Dr. Bernhard Dernburg (1865‐1937), representative of the German Red Cross, in charge of the German Press Bureau and Information Service, and former Colonial Secretary. Dr. Dernburg received much ink in The New York Times from the beginning of the war until he was hounded out of America in late June, 1915. He also hired former Wilson advisor William Bayard Hale (a leading American journalist) as a public relations man. The Germans also made use of American authors, including the Irish‐American author Frank Harris (1856‐1931), whose autobiography was banned in the US, the German‐American Frank Koester, and Professor Edwin J. Clapp of NYU. The Germans also utilized the peace movements to keep America out of the war as an Ally.

A major theme was the appeal to the American spirit of "fair play." Pro‐German propaganda was disguised as a righteous attempt to offset the alleged (and actual) pro‐Entente bias of the American press and elites. Dr. Hugo Münsterberg even dedicated his The War and America "to all lovers of fair play." They mined American history to find examples of British offenses against the United States and other nations with many emigrants in America, such as Ireland. The Germans also reached out to American minorities, notably the Negroes and the Jews. The German propaganda reached America via Italy until the latter entered the war, after which it flowed through Holland and Scandinavia. Once it reached American shores, a variety of groups distributed it. Chief among them was The German‐American Alliance (also known as "The National German‐American Alliance"), founded in 1901 and chartered in 1907. By 1914, it had over 2,000,000 members in branches in over 40 states. It was especially important in St. Louis, Chicago, Milwaukee and Cincinnati and was "the largest ethnic organization of its kind in American history." It was limited to citizens but it also worked to naturalize immigrants. The 6,000‐plus Lutheran congregations in America also passed on bulletins from the German Press Bureau and Information Service. Germany purchased the New York Evening Mail for $1,500,000 to reach urban readers. Count von Bernstorff noted the utility of libraries, especially the Library of Congress, in spreading the message around.

Despite these arrangements, the Germans, as did the British, preferred to reach out to influential individuals. The German embassy had a list of 60,000 people, mostly through the manifests of the Hamburg‐Amerika Linie (a passenger shipping company) and the efforts of the German Werkbund, ostensibly dedicated to arts, crafts, and German daily life but who also gathered names of foreign neutrals who could distribute pamphlets to the citizenry and press of their countries. Politicians, clubs, and colleges were also included.

4. Blunders by the Central Powers

Several incidents particularly damaged German propaganda efforts in America; the last of which,

the infamous "Zimmermann Telegram," actually led to America’s entry into

the war. The damage actually started well before the war when the American public believed a

story that a German squadron had molested the American fleet after the battle of Manila Bay and

when President Theodore Roosevelt invoked the Monroe Doctrine against German military threats to

recover debts from Venezuela.  The sinking of the S.S. Lusitania on May 7, 1915 (which the

Germans blamed on the British putting American passengers on an armed munitions ship) and the

execution later that same year of Edith Cavell, the British nurse who confessed to helping

Entente prisoners escape in Belgium gave Germany black eyes and created much work for German

apologists. One modern analyst describes the latter event as "every propagandist’s

dream come true" [See Appendix 2].

The sinking of the S.S. Lusitania on May 7, 1915 (which the

Germans blamed on the British putting American passengers on an armed munitions ship) and the

execution later that same year of Edith Cavell, the British nurse who confessed to helping

Entente prisoners escape in Belgium gave Germany black eyes and created much work for German

apologists. One modern analyst describes the latter event as "every propagandist’s

dream come true" [See Appendix 2].

A few months later, on July 24, Dr. Albert made the mistake of falling asleep on the El in New York. When he awoke at his stop, 50th Street, he left in such a hurry that he forgot his briefcase (in which were carried papers concerning German propaganda efforts in America) on the train. By the time he realized his mistake and got back into the car, another man had walked off with it. Unfortunately for Germany, that man was a US government agent, Frank Burke, of the Secret Service. The papers were passed to the New York World for publication. The first installment appeared on August 15. Not surprisingly, many Americans were outraged, presumably at the evidence Germans were trying to play them for saps. Indeed, US Secretary of State (1915‐20) Robert Lansing later admitted that "[t]he purpose of publishing this interesting correspondence of Doctor Albert was to counteract, in a measure, the political effect of the slanderous articles on the government and its officials, which were constantly appearing in the newspapers and periodicals receiving subsidies from Germany."

On August 30 of that same year, British authorities detained James Archibald, an American journalist working for the Central Powers and en route to Germany from America. In his luggage, the British found an intemperate letter from German Military Attache Franz von Papen noting that "I always say to these idiotic Yankees that they should shut their mouths and better still be full of admiration for all that heroism (of Germans on the Eastern Front)." This was bad, but the bombshells were papers from the Austro‐Hungarian ambassador to Washington, Constantin Theodor Dumba, to his government. These reports proposed and requested money to subsidize labor agitation among American munitions workers of Austro‐Hungarian descent. Dumba also urged agitation in America to affect (pro‐Allied) American foreign policy. The British published these papers, which excited great anti‐Central Powers feeling among Americans. President Wilson asked Dumba and Bernstorff to cease their propaganda activities (they complied). On September 8, the State Department declared Dumba persona non grata and he left America on September 30. The day before the State Department’s action, the New York Times declared "Never before has there been another diplomatic representative who has in such an open and unabashed way taken measures to make himself altogether unacceptable"; and on September 23, the Boston Post gloated in rhyme, "O Constantin Theodor Dumba/ You’ve roused Uncle Sam from his slumba:/ That letter you wrote/ Got the old fellow’s goat‐‐/ Now his path you’ll no longer encumba! [sic]" The Dumba‐Archibald Affair put paid to Central Powers propaganda in the United States.

The final blows in America for Germany and her allies were the resumption of unrestricted submarine warfare and the Zimmermann Telegram in early 1917. The latter was a telegram from the German Foreign Secretary Arthur Zimmermann to Bernstorff, to be relayed to the German ambassador in Mexico City, promising the Mexicans much of the land they had lost to their northern neighbor seventy years previously, should Mexico join in an attack on America as a Central Power. The British intercepted and decrypted the telegram and sent it to Washington. Wilson released it to the press on March 1. Public opinion, as well as that of Congress, demanded war against Germany, which was declared on April 6, 1917.

5. British Propaganda Machinery

Despite a later start and greater disorganization than their rival, the British were much more effective in America. "British propaganda actually dwarfed German propaganda." A major reason for this was that the Entente powers, especially the United Kingdom, dominated the influx of war news to America. Britain had, however, more propaganda machinery than the newspapers, although the exact origins of Britain’s World War One propaganda are unclear and there appears to exist no evidence of pre‐war planning for propaganda organizations. Even on the outbreak of war, Germanophobia combined with great pro‐war patriotism and the expectation of a quick victory to make the organization of propaganda resources appear irrelevant. Early British propagandists shared with their foes an inexperience in the matter; moreover, they lacked enthusiasm for the task of molding public opinion. 1914‐’15 British work was essentially "cautious and defensive," although they increasingly used aggressive counter‐propaganda.

In fact, Admiral Sir Reginald Hall, the head of British Naval Intelligence and his Naval Attaché in Washington Sir Guy Gaunt realized a major counter‐propaganda event would be the exposé of Central Powers' activities in America, especially those which endangered US neutrality. Largely through the help of Emmanuel Voska, a colleague of Thomas Masaryk, Gaunt developed a wide net of counter‐propaganda agents in the States. Sir Gilbert Parker of the Foreign Office saw to it that that books by "extreme German nationalists, militarists, and exponents of Machtpolitik such as von Treitschke, Nietzche, and Bernhardi" were published in English in America. According to analysts it was a brilliant move and helped to demonstrate a unity of interests between the Entente and the United States. It was also a relatively subtle way of painting the Germans as barbarians—letting them do it to themselves.

The British relied on quality rather than quantity, in direct contrast to the Germans, who blanketed the US with continuous, blatant propaganda. This may be one result of the fact that until 1918 British propagandists had only Asquith’s points of November 9, 1914 upon which any peace would be based: the restoration of Belgium, the protection of France from "future German aggression," the recognition of "the rights of small states," "and an end to Prussian military domination of Germany."

The British worked to exploit their supremacy in newspapers. One early propaganda organization was the Press Bureau. It was divided into four parts including an Issuing Department which was the conduit for official government information to the press and the Military Room which dealt with all press material other than cables. The Press Bureau had to struggle against the prohibition of using clear "terms of reference nor any specific definition of duties." In addition, the military did not trust Fleet Street; consequently, the former did not use much of the latter’s vast propaganda potential in the early part of the war. The War Office so feared the publication of military information that it banned war correspondents from the front until May, 1915.

On September 11, 1914, the Press Bureau and the Home Office formed the Neutral Press Committee to disseminate news to friendly and neutral nations. It was placed under G. H. Mair, formerly the assistant editor of the Daily Chronicle. Two committees having failed to establish control, Mair was responsible only to the Home Office until early 1916. He collected summaries of foreign news to track changes in public opinion overseas to help his propagandists. He divided the Neutral Press Committee into four parts which arranged the "exchange of news services between British and foreign newspapers; the promotion of the sale of British newspapers abroad. . ., the dissemination of news articles among friendly foreign newspapers and journals; and the transmission of news abroad by cables and wireless." Mair allowed neutral journalists to write their own articles after giving them official information. This was of special importance to American journalists. It helped camouflage the official source of the propaganda, thus making it more palatable to the public. This was in direct contrast to the German model which was usually discounted by the educated, targeted American audience.

Another early introduction was the News Department which was formed by the Foreign Office to issue news to journalists. It also compiled news articles with the Press Bureau and the NPC to cable to lands such as the United States that were too far away for effective wireless dissemination. The News Department also had two transmitters of its own at Poldhu and Caernarvon in Wales with which to supplement Reuters news services. Caernarvon could reach the east coast of the United States. News Department officials tried very hard to operate on a friendly, personal basis with newsmen. Its head, Lord Robert Cecil, was one of the few Foreign Office men who saw the propaganda potential of the press and he worked to resolve Press Bureau‐Fleet Street issues. He successfully lobbied the service departments for weekly military affairs seminars for the press. This program was judged very successful. In December 1915, it succeeded in abolishing censorship regarding foreign affairs, putting responsibility on the individual newspapers. This led to a new era of openness between the Foreign Office and the press, while also allowing the News Department to concentrate on propaganda. What actually happened was rather than act directly, the News Department used the press to disseminate propaganda. It also provided news reports to be used for propaganda by consular and diplomatic staffs in foreign countries. Just like the Germans, the British diplomats distributed pamphlets and the like. They frequently put them in waiting rooms to reach bored, casual readers. These staffers represented "one of the most significant contributions of the Foreign Office toward the conduct of British propaganda in the First World War."

The British military also got into the propaganda act. MO5 (h) was created within the War Office in February 1916 to handle propaganda from the military end. It received its more familiar name of MI7 after a January 16 (1917?) reorganization and the creation of the Directorate of Military Intelligence. MI7 was run until December 1916 by Lieutenant‐Colonel Warburton Davies, and subsequently by Major J. L. Fisher. As seems to have been customary in British propaganda organizations, it was divided into four groups, the most important of which handled the production of materials. Others dealt with censorship, one with visits to the front, and one with collecting foreign press summaries.

The Admiralty outstripped the War Office. Thanks to the activities of Sir Reginald "Blinker" Hall, the Director of Naval Intelligence and Captain Guy Gaunt, the admiralty led in the organization of propaganda. Gaunt was the head of Naval Intelligence in the US and a liaison with Wilson’s advisor Colonel Edward M. House. The two got on so well that House wrote to the British Foreign Secretary Arthur Balfour:

"I want to express my high regard and appreciation of Captain Gaunt. I doubt whether you can realize the great service he has rendered our two countries. His outlook is so broad and he is so self‐contained and fair‐minded that I have been able to go to him at all times to discuss, very much as I would with you, the problems that have arisen."

Gaunt and Hall realized that a major counter‐propaganda event would be the exposé of Central Powers' espionage activities in the US, especially those which endangered US neutrality. Gaunt also liaised with Emmanuel Voska, a colleague of Masaryk, who had developed the spy network mentioned above. Colonel House also became friendly with Gaunt’s temporary replacement as liaison, William Wiseman, the head of Bristish Military Intelligence in America. Gaunt and Wiseman became rivals and the latter won out as conduit between House and Balfour upon America’s intervention.

The most important British foreign propaganda outfit was the War Propaganda Board, more commonly called after the location of its offices "Wellington House." Wellington House was formed in response to the need, identified by then Chancellor of the Exchequer David Lloyd George, to counter and correct the torrent of German propaganda, especially in the US. Prime Minister Asquith tasked Charles Masterman with creating an organization for justifying Britain’s entrance into and conduct of the war to neutral and Dominion countries. By 1917, Wellington House had 54 staffers, making it the largest British foreign propaganda organization. Its governing body, which met daily, was "The Moot" and included advisors such as Arnold Toynbee and Lewis Namier. Wellington House operated in such secrecy (in order to conceal the official provenance of their documents so they should more easily be believed) that not even Parliament was aware of it. It used well‐known private figures, private printers, and private shipping to mask the official nature of its propaganda. Its practice was established through two conferences in September 1914. The first consisted of stellar literary people such as J. M. Barrie, G.K. Chesterton, Arthur Conan Doyle, and H.G. Wells. The second hosted representatives of the press, including the Pall Mall Gazette and The Standard. This latter conference came out with four unanimous resolutions. It resolved:

1.That it is essential that all the unnecessary obstacles to the speedy and unfettered transmission of news should be done away with and that all matter which has appeared or has been authorized to appear in English newspapers should be put upon the telegraph wires and cables without further censorship or delay in London.

2. That every effort should be made by the Government to procure special facilities for news messages by cable from England to neutral countries, especially those where German news at present obtains precedence.

3. It is recommended that an official be appointed by the Foreign Office to receive London correspondents representing all newspapers in the Dominions and neutral countries and to give them such information as, in the opinion of the Foreign Office, is desirable. . . .

Despite their claim that "our activities have been confined to the presentation of facts and of general arguments based upon facts," the War Propaganda Board was the official organization most responsible for earning the British a reputation for lurid propaganda. In fact, its refusal to lean on its writers led to frequently "inconsistent and contradictory" propaganda. Many of its workers had previously worked for the National Insurance Commission, which was created to justify the 1911 National Insurance Act, a rare example of pre‐war Government propaganda.

Wellington House relied mainly on pamphlets in the first part of the war. Although it used the press more extensively as the war went on, pamphlets were still prioritized because it was hard to disguise the official nature of a press article. These pamphlets emphasized facts so readers could make up their own minds. There was also a small charge for the pamphlets because, as one modern writer observes, "people do not like to think they would buy propaganda."

Wellington House was divided into subsections based on language; the US was "a most important special branch" run by Canadian born writer and Member of Parliament Sir Gilbert Parker. At first, the goal was the negative one of keeping America neutral rather than the positive one of inducing American intervention; Britain needed American trade to offset the loss of German business. Later, as the United Kingdom became more dependent on America, the aim became getting America involved. Wellington House relied mainly on personal approaches; it aimed at opinion‐makers, not opinion itself. Its propaganda in America was written for an educated audience by such luminaries as H. G. Wells, Namier, and Toynbee, and was sent, along with a personal letter from Parker, to prominent Americans. He used Who’s Who to compile a list of notable Americans to approach. By 1917, he had 170,000 names. Parker also sent material to about 555 US newspapers; because, as one Briton observed, "through showing one important editor the concrete evidence of this country’s achievements, you can reach hundreds of thousands of readers."

Parker himself frequently visited the States giving talks, especially to the Society of Pilgrims. One other function of the War Propaganda Board was to undo the harm done in America by unofficial voluntary propaganda associations, such as the Central Committee for National Patriotic Organizations. By Spring, 1916, there had been a rationalization in which the NPC was amalgamated with the News Department and Wellington House was brought more under the Foreign Office. Lord Newton was the head of the new organization.

On New Year’s Day, 1917, Lloyd George appointed friend and editor Robert Donald to report

on the state of propaganda. The latter urged a more proactive strategy rather than responding to

the Germans. He also advocated the creation of a unified propaganda agency. By the time his

report came down, the cabinet had already accepted the idea. On February 9, 1917, Prime Minister

Lloyd George appointed the Scottish author John Buchan (1875‐1940) director of the new

Department of Information at a salary of 1,000 Pounds per annum. This did little to remedy the

plethora of semi‐independent propaganda agencies. Donald’s second Report in October

reiterated the critiques of the first and repeated many earlier recommendations, such as using

telephone links between the Allies and Switzerland.

6. British Propagandists

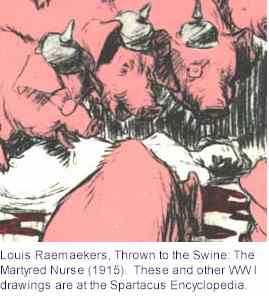

One of John Buchan’s earlier contributions had been to urge the use of the cartoons of the

Dutch artist Louis Raemakers (b. 1870), formerly of De Telegraaf, an influential Dutch

newspaper. His cartoons only ran in a few newspapers until America joined the fray. However, he

was useful both as a gifted artist and a neutral, which gave him a veneer of objectivity.

Another Dutch contributor was Prof. A.A.H. Struycken, who wrote a commentary on the German White

Book (defending German actions in Belgium) for "Van onzen Tijd" ("Of Our

Time") which was picked up, translated, and published in Edinburgh. Among the Americans who

took up the English cause was Dr. Charles W. Eliot (1834‐1926), the former President of

Harvard. For the British there were Lewis Namier and Arnold J. Toynbee. Namier

(1888‐1960) was actually born in Poland and emigrated to the UK. His notable books

include Structure of Politics at the Accession of George III, first published in 1929,

and England in the Age of the American Revolution, which came out in 1930. He was

knighted in 1952. Toynbee (1889‐1975) would achieve some fame for A Study of

History (12 volumes, 1934‐’61). He would work in the Foreign Office during

the Second World War as well as during the first. He was a prolific author and pamphleteer

during the Great War, exposing many atrocities committed by the Central Powers.

The events which were so damaging to the Germans were, reciprocally, boons for the

British—the execution of Edith Cavell, the repeated sinkings of passenger vessels carrying

Americans, such as the Lusitania and the Arabic (which was sunk on August 19, 1915 by a

U‐Boat), and the Zimmermann Telegram. The only serious sore point for the British was

their brutal repression of the Irish Easter Rising. In the end, through a combination of

pre‐existing conditions, their own good work and the ineptitude of the German leadership,

British propaganda won out.

7. The Underlying Preconditions for the War

One function of propaganda is to put forward one’s own view of the world and its history.

This was played out during the Great War by competing allegations about responsibility for the

war (naturally, neither side admitted guilt in this matter), atrocities, and political

superiority. The British generally took the offensive in these matters.

Both sides disputed who had created the preconditions for the war. For the British, the root cause was German imperialism, both abroad and in Europe. Namier took point and argued that the "fundamental principles" of German imperialism were "expansion and dominion, the very vagueness of its aims renders it the more universally dangerous; no compromise nor understanding is possible with a nation or government which proclaims a program of world‐policy and world‐power and yet fails to limit its views to certain definite objects." Namier argued that while it had failed to politically expand abroad, Germany had partially succeeded in seeding German colonies throughout Eastern Europe. Namier compared German eastwards expansion to an octopus surrounding the Czech lands and cutting them off from the Poles; he observed that "the whole history of the Tchech [sic] nation is the history of resistance against German encroachment." He compared contemporary Germany unfavorably to the Prussia which had initially unified the state. The new Germans did not see the limits recognized by their Prussian predecessors. Namier claimed that "had Germany kept to the line of foreign policy laid down by Bismarck, she would never have actively interfered in Balkan affairs." Kaiser Wilhelm II was the perfect embodiment of the new German imperialism.

"He is not only the chief. . . of the Prussian landed gentry, and the head of the Prussianized army, but also the imaginary descendent of medieval crusaders, the successor of anointed Holy Roman Emperors of German nationality, the Emperor of Kings, the sovereign of all the Germans, the chief German Kulturträger [culture‐bearer]. . . ."

For their part, the Germans tended to blame the British monarch Edward VII for creating the Entente of hostile states which encircled Germany. Professor John Burgess noted that Edward VII united Pan‐Slavic Russia (whose defeat in 1905 thrust her interest back on Europe), revanchist France, and jealous Britain; that his policies of encouraging Japan against Russia, inciting the French, "seducing" Italy, and creating the Entente threatened Germany and the Dual Monarchy. Frank Koester declared that Edward VII’s encircling Germany with the Entente was the immediate cause of the war. Dr. Münsterberg summed things up by observing

"the spark was thrown by the Servian [sic] murderer of the Austrian archduke; the explosive was heaped up by King Edward VII, who created the mighty alliance of Great Britain, Russia, and France; but the powder was made from the political jealousy of Europe against ascending Germany."

This jealousy consisted for the French of reversing 1871 and regaining the lost provinces ("the chattering of a monkey for his peanut which did not originally belong to him [i.e. Alsace‐Lorraine was traditionally German]"), for the Russians, it was the control over the Balkans in aid of Pan‐Slavism, and for the British it was commercial jealousy and the preservation of the balance of power in Europe. The Central Office for Foreign Services announced that Germany

"saw clearly that there was no escaping the design to attack her simultaneously from three sides. France demanded revenge: [sic] England demanded the destruction of Germany’s commerce, and Russia demanded the downfall of Austria‐Hungary and supremacy over all Slavic nations. Each of these claims is in itself a declaration of war."

Frank Koester questioned rhetorically whether, given the conditions that [allegedly] threatened

Germany, America could have kept the peace as long as Germany did—forty years.

8. Austria or Serbia?

The actual trigger was the assassination of the heir to the thrones of the Dual Monarchy Franz Ferdinand on June 28, 1914 by an ethnic Serb armed with a Serbian pistol provided by a Serbian secret society dedicated to a "Greater Serbia" and run by a the head of Serbia’s military intelligence, and the Austrian response, which was an ultimatum making such demands on Serbia’s sovereignty that it would be rejected, which rejection would be a casus belli. Since educated opinion is still divided on the subject, it is not surprising that both alliances claimed the mantle of victimhood. "Shamrock" argued:

"....less than a year after the Treaty of Bucharest [ending the Second Balkan War], came the crime of Sarajevo and Austria’s infamous attempt to make it the pretext for destroying the liberty of a kingdom. Weak as she was from her double conflict, Serbia was in no position to offer battle single‐handed to an enemy far more powerful than either of the others. If one thing is certain among the tortuous events of that time, it is that Serbia did not want war.

James H. Beck, the former Assistant Attorney General of the United States (1900‐1903) declared "[I]t would be difficult to find in history a more offensive document [than the Austrian ultimatum]." "Shamrock" expressed incredulity that the ultimatum was intended to be taken seriously and emphasized the extent of the Serbian concessions. He (she?) called the Dual Monarchy a bully.

The Germans and their sympathizers saw things a bit differently. A German official document asserted the Austro‐Hungarian investigation into the assassination had found the plot was hatched in Belgrade and helped and armed by Serbian officials.

This crime must have opened the eyes of the entire civilized world, not only in regard to the aims of the Servian policies [sic. The aims would be the creation of a Greater Serbia by splitting off the South Slav parts of Austria and incorporating them] directed against the conservation and integrity of the Austro‐Hungarian monarchy, but also concerning the criminal means which the pan‐Serb propaganda in Servia [sic] had no hesitation in employing for the achievement of these aims. . . . In this manner for the third time in the course of the last six years, Servia [sic] has led Europe to the brink of a world war.

Professor Burgess and the authors of the German White Book agreed that Serbia was looking to avoid performing what the Austrians felt was their duty to detect and punish the Serbians responsible for the murder and that the Dual Monarchy had to take the actions the Serbians would not. Nevertheless, there was at least one other party responsible for the Serbian temerity and rejection of the ultimatum—Russia. The German Foreign Office claimed that Serbia would not have acted without Russian support. The Central Office for Foreign Services declared "...come what may, the House of Habsburg must be sustained in its defense against Russian arrogance, or be doomed to voluntary disintegration by further tolerating Servian [sic] demoralizing interference and allowing murder to go unpunished." And Frank Koester claimed that Serbia would have given in if she not been backed by Russia and Britain.

While the events and claims of the days leading to the general war are very confusing to sift

through, some facts are relatively clear and provide a framework for understanding the claims

and counterclaims regarding war guilt. Austria‐Hungary delivered the ultimatum to Serbia

on July 23. The next day, the Imperial and Royal [Austro‐Hungarian] Army partially

mobilized. Serbia called up its reserves on July 25, the day it responded to the ultimatum.

Austria‐Hungary declared war on Serbia on July 28, 1914. The next day, Russia mobilized

in support of Serbia against the Dual Monarchy, but not yet against the Germans. The latter then

began mobilizing. The next day Nicholas II authorized full mobilization. Meanwhile, Wilhelm and

Nicholas, who were friends and first cousins, were telegraphing each other, trying to prevent a

Russo‐German war. Austria mobilized against Russia on July 31. France called up her

troops the same day. On August 1, Germany declared war on Russia, who changed the name of her

capital from the Germanic "Saint Petersburg" to the Russian "Petrograd." On

August 2, the first German patrols crossed the French border. That same day, Germany requested

free passage through Belgium. The Belgians refused. On August 3, Germany declared war on France

and invaded Luxembourg and Belgium, while at the same time crossing into Russia in the east. On

August 4, Britain, which had demanded Germany not violate Belgian neutrality, declared war on

Germany.

9. Whose Fault was the Wider War?

Europe was at war. Not surprisingly, both alliances tried to fob the responsibility for the conflict on the other, while posing as the workers for peace. Lewis Namier’s analysis was that the first war was fought because of Austria‐Hungary’s internal problems. However, both Thomas G. Masaryk and James H. Beck claimed that Austria was a pawn of Germany, who knew and approved of the Dual Monarchy’s policy toward Serbia. Masaryk closed his introduction by pleading for "the long deserved punishment" of Austria for having attacked Serbia and "by this unleashed the dogs of war." As for Serbia’s protector (Russia), it was not expected to abandon her because while the Austrians sent the ultimatum, "the voice which sanctioned it was the voice of the arch‐plotter beyond the Rhine." Moreover, Austria’s minorities, largely Slav, did not want the war. Russia, far from stiffening Serbia, as the Germans claimed, urged the Serbians to yield, while the Germans urged the Austrians on. Meanwhile, Sir Edward Grey, the British Foreign Secretary, proposed a four‐power (Britain, France, Germany, and Italy) conference to mediate while Russia pleaded for time to resolve the issue. Beck asked, rhetorically,

"....[d]oes any reasonable man question for a moment that, if Germany had done something more than merely ‘transmit’ [Grey’s plea to accept Serbia’s response or at least see it as a framework for negotiations], Austria would have complied with the suggestions of its powerful ally or that Austria would have suspended its military operations if Germany had given any intimation of such a wish?"

Beck went further and claimed that Germany’s excuse that Russian mobilization required the German response did

"...not justify the war. . . . If Russia had the right to mobilize because Austria mobilized, Germany equally had the right to mobilize when Russia mobilized, but it does not follow that either of the three nations could justify a war to compel the other parties to demobilize."

Beck, the former assistant attorney generalof the U.S., complains that, while the British and Russians had published all relevant documents (in books of various hues, the British being white), the Germans, and especially the Austrians, had not. This was a "significant omission and one which casts doubt upon the Central Powers’ case."

Dr. Bernhard Dernburg responded to just this point when he condemned "Lord" Bryce for basing

"...his argument [that Germany’s violation of Belgium brought Britain into the war] on the expressions in the so‐called White books. To these White Books Americans give a great deal of credit. I cannot follow. I know how they are made up (unfavorable diplomatic documents are omitted)."

The Germans for their part portrayed themselves as peacemakers alongside Britain, but they inadvertently admited responsibility for encouraging an Austro‐Hungarian assault on Serbia, which despite German efforts to limit the conflict, expanded into a world war. The German Foreign Office states that it worked with England to

"...gain the possibility of a peaceable solution to the conflict. . . . Austria‐Hungary should dictate her conditions in Servia [sic]; i.e. after her march into Servia [sic]. We thought that Russia would accept this basis."

Nevertheless, Germany rejected Sir Edward Grey’s proposal because "we could not call Austria in her dispute with Servia before a European tribunal." In any case, Vienna rejected the proposal. The Germans largely blamed the war on the Russians for supporting the Serbians. The German Foreign Office complained about the failure of the British, French, and themselves, to prevent Russia from intervening, even though Austria‐Hungary assured Russia it had no territorial demands in Serbia. According to the Germans, the news of Russian mobilization came on July 26. German diplomats in London, Paris, and Saint Petersburg were instructed to "energetically" warn of the consequences of this mobilization—war versus Russia and France (the latter allegedly because it stood by Russia, but not in small part because the German mobilization and battle plan, the "Schlieffen Plan" called for simultaneous attacks on the two and could not be easily be changed). The Germans charged that the Russians had deliberately brought about the war while the Germans were working for peace in Vienna. The servants of the Hohenzollerns complained about Russian double‐dealings. Indeed, the first chapter of The German White Book is entitled "How Russia and her Ruler Betrayed Germany’s Confidence and thereby Caused the European War." According to this argument, Russia was mobilizing while the Russian War Minister, Ssuchomlinow [sic] gave his word of honor it was not. Münsterberg describes the Kaiser begging his cousin to halt mobilization "and he reminded him of his pledge to his dying grandfather to keep peace with Russia as long as possible" and reminding "Nicky" that Germany had consistently helped Russia.

Not only did the Tsar not suspend mobilization, he signalled the French to mobilize. The

Norddeutsche Allgemeine Zeitung (North German General News—a paper that

seems to have acted like an official mouthpiece for the German Foreign Office) complained that

Germany had had to mobilize in the face of this obvious double‐dealing on the part of

Russia. Just as the British blamed the Germans for not restraining the Austrians, the Germans

turned the tables, blaming the British and French for not restraining the Russians. The Germans

claimed that Germany was prepared to spare France in case England should remain neutral and

would guarantee the neutrality of France. In fact, the German battle plan already called for an

attack into France. The German Secretary of State Gottlieb von Jagow claimed that "the

moral responsibility" for the war lay with Britain who encouraged the Belgians to resist

and encouraged the "chauvinistic anti‐German tendencies in France and Russia."

Moreover, Britain’s failure to restrain the flames of a war that Germany fanned put the

blame on the former. Münsterberg declared that "Surely, although Germany made the

declaration [of war against Russia and France], this is a war against Germany, and it is a sin

against the spirit of history to denounce Germany as the aggressor."

10. The Germans Blame Belgium

The issue of the invasion of Belgium was very important not only because it allegedly brought Britain into the war but also because it gave Germany a bad reputation in the United States where a people who prided themselves on standing up for the underdog were offended by the bully of the block (Germany) beating up on the little kid with glasses (Belgium). Dr. Charles Eliot, late President of Harvard, condemned the invasion of Belgium and the German "might makes right" ideology. Alleged German behavior in occupied Belgium, thoughtfully described for Americans by the British, offended American senses [See Appendix 3].

The Germans had four main arguments justifying what most modern historians agree was an invasion: Belgium was not really neutral; its neutrality was first violated by France; even if Germany did invade Belgium, it had to do so; the Belgians should not have defended their neutrality.

On October 12, 1914, the Norddeutsche Allgemeine Zeitung complained that Belgium, whose perpetual neutrality had been guaranteed in an 1839 treaty by France, Britain, Prussia, Russia, and Austria, had behaved unneutrally by cooperating with the British, not planning a defense against a French invasion, and not reaching a neutrality agreement with Germany. Therefore, Belgium brought the invasion upon itself. In fact, the Schlieffen Plan called for an invasion of Luxembourg and Belgium (originally Holland as well) in order to hit the flank of the French forces correctly expected to attack into Alsace‐Lorraine. The main justification for Germany’s first charge was a cache of Belgian Defense Ministry documents captured by the Germans in Brussels. These referred to 1906 meetings between the British military attaché and Belgian officers to discuss British intervention in Belgium in the event of a Franco‐German war. They were interpreted to mean Britain had plans to violate Belgian neutrality herself. Frank Koester quotes Lord Roberts in 1911 as saying a British expeditionary force and the Royal Navy were ready "to embark for Flanders to do its share in maintaining the balance of power in Europe" and a Belgian military official as claiming "at the time of (the Moroccan Crisis of 1912) the British government would have immediately effected a disembarkment in Belgium, even if we had not asked for assistance. . . . Since we were not able to prevent the Germans from passing through our country, England would have landed her troops in Belgium under all circumstances." However, none of the documents reprinted indicate a British intention to invade Belgium; they all presuppose an initial German incursion. In fact, a margin note on one of the German‐reproduced papers observes "L’entrée des Anglais en Belgique ne se ferait qu’apres la violation de notre neutralité par l’Allemagne" (The entrance of the English into Belgium would only be done after the violation of our neutrality by Germany). The Norddeutsche Allgemeine Zeitung of November 24, 1914 accepted Belgium’s right to plan with the British a defense against German attack but complained that the Belgians had not made similar plans with Germany to defend against the Anglo‐French forces and that "The Belgian government had decided from the first to join Germany’s enemies and to make her cause one with theirs." Dr. Münsterberg asserted that "Belgium chose to put itself on the side of France, with which its sympathies have always connected it. . . .Belgium was one great fortified camp [against Germany]." In fact, according to the Germans, the French had beaten them to the punch—France had guns and troops in Belgium by July 30 and the British had landed in Ostend the same day. Dr. Münsterberg complained that "when Germany goes through Belgium, America shares the indignation of England [who, according to Münsterberg’s colleague Dr. Dernburg, had actually invaded Belgium itself] to which it serves as a welcome pretext. But that France went into Belgium first is kept a secret in most American papers. This means playing the reporter’s game with loaded dice." However, German Prime Minister Betthman‐Hollweg declared:

"We are now in a state of necessity, and necessity knows no law. Our troops have already occupied Luxemburg [sic] and perhaps are already on Belgian soil. Gentlemen, that is contrary to the dictates of international law. . . . A French movement upon our flank upon the lower Rhine might have been disastrous. So we were compelled to override the just protest of the Luxemburg [sic] and Belgian Governments."

Dr. Münsterberg attempted to take the edge off Germany’s invasion by citing the necessity to invade Belgium to preempt the French and argued "Germany did not come to Belgium as an enemy; it promised to repay any damage and not only guaranteed the integrity of the land but was most willing to make every possible restitution."

Germans, with some justification, condemned what they took to be the hypocrisy of the British claim to have gone to war over Belgium. Münsterberg observed:

"it was. . . especially absurd when England claimed that it had to go to war because it could not tolerate the moral wrong of Germany’s using the Belgian railways—England which had broken pledges upon pledges in Egypt, in Tibet, in South Africa. . . ."

Dernburg agreed, noting that Germany had a much better record of honoring treaties than did the Allies, including Japan. Koester carped that:

"the crowning piece of British hypocrisy in the present war was the great holier‐than‐thou violation of Belgian neutrality. From a nation which for hundreds of years has fattened off of the life blood of subjected races such a protest was an unparalleled piece of national cant."

The effect of these claims on American public opinion is unknown, although this author would

guess that the implied criticism of the treatment of the Irish in Koester’s declaration

may have hit home for some Irishmen in America. However, the inconsistency in German arguments

about Belgium probably did not impress many observers, especially given the pro‐British

trend in the press.

11. Atrocity Propaganda

The British took the offensive in publicizing atrocities allegedly or actually committed by soldiers of the Central Powers. They focused on German and Turkish massacres, especially of Armenians, to obscure Russia’s reputation among American Jews. The British particularly hyped German behavior in Belgium, whose citizens and valiantly resisting army already had the sympathy of many Americans [See Appendix 4].

The most important document spreading reports of German misbehavior (giving British propaganda a reputation for purple prose and, ironically, after being debunked after the war, contributing to a discounting of reports about the Holocaust twenty‐five years later) was "The Bryce Report" with its appendix. Officially called The Report of the Committee on Alleged German Atrocities, it was published in an American edition and many Americans accepted the truth (later found to be much exaggerated) of the Bryce Report because Viscount Bryce, the chairman of the committee, had been the ambassador to the United States (1907‐1913). The Report "had a profound and shocking impact on the United States." The committee had been appointed by Prime Minister Asquith on December 15, 1914. In keeping with the British striving after the appearance of objectivity, the authors of the report stressed the legal knowledge of the examiners taking the depositions of Belgians and Britons and that:

"they were instructed not to ‘lead’ the witnesses, or make any suggestions to them, and also to impress upon them the necessity for care and precision in giving their evidence. They were also directed to treat the evidence critically. . . . They were, in fact, to cross‐examine them. . . ."

The Committee also avowed it included "in full" all statements "tending to exculpate the German troops" and rejected any testimony from questionable witnesses. Nevertheless, the Committee declared:

In the present war, however—and this is the gravest charge against the German army—the evidence shows that the killing of non‐combatants was carried out to an extent for which no previous war between nations claiming to be civilized (for such cases as the atrocities perpetrated by the Turks on the Bulgarian Christians in 1876, and on the Armenian Christians in 1895 and 1896, do not belong to that category) furnishes any precedent.

Arnold J. Toynbee draws heavily on The Report for his own The German Terror in Belgium: An Historical Record. Because atrocities occurred wherever the Germans advanced, but only for the first three months of the war, Toynbee concludes "the systematic warfare against the civil population in the campaigns of 1914 was the result of policy, deliberately tried and afterwards deliberately given up.

The general themes of the Appendix to The Report, which contains all the depositions on which the report was based, were seeing dead bodies, the use of civilians as human shields, German threats, gang rape of civilian women, the abuse of the young and old, the taking of hostages, and looting. An example of the stories the British played up is:

I saw eight German soldiers. . . .They were drunk. . . .They were singing and making a lot of noise and dancing about. . . .As the German soldiers came along the street I saw a small child, whether boy or girl I could not see, come out of a house. The child was about 2 years of age. The child came into the middle of the street so as to be in the way of the soldiers. The soldiers were walking in twos. The first line of two passed the child; one of the second line, the man on the left, stepped aside and drove his bayonet with both hands into the child’s stomach, lifting the child into the air on his bayonet and carrying it away on his bayonet, he and his comrades still singing.

It is easy to see why an audience not yet exposed to the exaggerations of propaganda could readily believe and be appalled by this and come to anti‐German sentiments; almost everybody hates to think of children being mistreated. Another group to which Americans felt protective is women. The British pushed this button as well. The Appendix quotes a Belgian "married woman" who claimed to be pregnant after being raped by two soldiers of the German 49th Infantry Regiment. There were not infrequent references to Germans cutting off women’s breasts. Clergy also came in for rough handling by the occupying power. The Appendix and Toynbee also recount episodes in which Germans took out on civilians their frustrations at being repulsed or forced to retreat by the Belgian army. In addition to crimes against civilians, the Germans were accused of many instances of looting and arson. The most noted case was the burning of the university town of Louvain in which the library, repository of priceless ancient documents, was torched.

The main justification presented by the Germans for their actions against Belgian civilians was legitimate retaliation against francs‐tireurs (civilian snipers) or Belgian soldiers, especially in Louvain [See Appendix 5]. Toynbee points out incidents in which, to avoid embarrassment, cases of German friendly fire were blamed on Belgian francs‐tireurs, leading to reprisals against innocent Belgians, while The Report emphasized the fact that the Belgian government assiduously warned its citizens not to act against the Germans. Toynbee was not impressed with the evidence presented by the Germans that their victims in Louvain were actually Belgian soldiers or francs‐tireurs. He described how several German soldiers disguised as francs‐tireurs fired on the Secretary of the American Legation at Brussels, Mr. Gibson, who was in Louvain "to enquire into the catastrophe" and were then "captured" by his escort in order "to give Mr. Gibson an ocular demonstration that the civilians had fired." In his commentary on the German White Book [not the one cited earlier] justifying German behavior, Professor Struycken declares:

"In considering why the German White Book [sic] has in so many respects so little justifying power, one discovers the chief reason in the fact that in justifying the cruel punishments administered to the citizens of Belgium so little direct evidence. . . has been collected, or at any rate, published. What we have before us consists far too much of supposition, guesses, assurances for the truth of which no satisfactory grounds are given."

Arnold J. Toynbee wrote a book on the massacre of the Armenians in which American sources are emphasized. Many of his themes recapitulate the Belgian descriptions. In the forward, Viscount Bryce estimated 800,000 Armenians had been killed in 1915.He emphasized that the killings were by government order, not by popular Muslim passion. Toynbee concentrated on the sufferings of women and children. He related a story about a woman who threw

"her dying child down a well, that she might be spared the sight of its last agony." An American "saw a girl three and a half years old, wearing only a shirt in rags. She had come on foot. . . [sic] She was terribly spare, and was shivering from cold, as were also all the innumerable children I saw on that day."

Toynbee alleged children under twelve were frequently handed over to "fanatical" Dervishes to be raised as Moslems or given as labor to farmers, while their sisters were placed in "houses" to service the Young Turks. As in reports from Belgium, crimes against ecclesiastics were emphasized. Toynbee puts the ultimate responsibility on the Germans who supported the massacres, could have intervened to stop the killing and deliberately did not. "It is impossible to doubt that those German consuls [in the towns from which the Armenians were deported] could have saved the Armenian nation, if they had taken steps to do so, or to suppose that the German Government was not informed of what was happening in good time."

British propagandists also described atrocities in Austria‐Hungary. The Czech National Committee in London wrote a book describing the suffering of the Czechs and Slovaks, using a Dr. Kramarzh, a leader of the "Young Czechs", who was arrested on a charge of high treason at the behest of the Imperial and Royal Supreme Military Command and sentenced to death on June 3, 1916, as a metaphor for the suffering of the nations. Masaryk declared that Austria‐Hungary was not only at war with Russia and Serbia but also with its own minorities. .The Czechs argued that the Czech lands had suffered terribly at the hands of the Austrians and it was futile to hope the Dual Monarchy would treat its nations fairly. "The fact that the Government was obliged [by arrest or flight] to get rid of the leaders of the nation shows what the real situation in Bohemia is." The property of Czech soldiers captured by the Russians or fighting for the Serbians was confiscated and the pensions for their families were suppressed. They asked "[h]ow many women and children are reduced to starvation to satisfy the vengeance of the Austro‐Germans." The Slovaks were also suffering as well. "The country is absolutely dead, and [Prime Minister] Tisza’s Magyar Government flaunts its triumph upon ruins."

Other (alleged) atrocities the British brought to the attention of the world were Zeppelin raids on British towns [See Appendix 6],U‐Boat warfare, especially concerning the Lusitania, Arabic, Sussex (sunk March 1916), and the return to unrestricted submarine warfare in January of 1917; the deliberate starvation of Poland, the murder of prisoners; and an incident in which, during a cholera epidemic at the POW camp at Wittenberg, the German medical staff left the camp, allowing the British to die or take care of their own problems.

The Germans responded in two ways to this atrocity propaganda. One way was to emphasize the good the Germans were doing [see Appendix 7] and the buildings the Germans did not destroy. A photo caption in the War Chronicle was captioned "Old patrician houses in Gent [sic], which remained intact as the inhabitants of the town did not offer any resistance to the German troops." They juxtaposed their reverent treatment of churches with the plunder of the Russians in East Prussia. The Germans also complained about the use of "dum‐dum" (exploding or expanding bullets outlawed by the Hague convention), the mistreatment of prisoners of war by the Entente forces, the shooting or capturing of corpsmen, and the violation of the Red Cross.

12. The Focus on America

There were also propaganda elements aimed distinctly at Americans. The war itself was placed in an American context: "If a cruel fate were to deliver the province of West Prussia with its capital Danzig to the Slavs, it would be as if New England were handed over to Mexico as a Mexican colony with General Villa as dictator in Boston."

One campaign was to convince the Yankees that their side had the political system most worth supporting (and the other did not). The British condemned "German [or Prussian] militarism." The Report opined that

[I]n the minds of Prussian officers War seems to have become a sort of sacred mission, one of the highest functions of the omnipresent State, which is as much an army as a State. Ordinary morality and the ordinary sentiment of pity vanishes in its presence, superceded by a new standard which justifies to the soldier every means that can conduce to success, however shocking to a natural sense of justice and humanity. . . . The spirit of War is deified. Obedience to the State and its warlord leaves no room for any other duty or feeling. . . .It is a specifically military doctrine, the outcome of a theory held by a ruling caste who have brooded and thought, written and talked and dreamed about War until they have fallen under its obsession and been hypnotised [sic] by its spirit.

Professor Struycken quoted the German Great General Staff’s German War Book which warned officers against humanitarian values "which not seldom degenerate into ‘Sentimentalität’ [sentimentality] and . . . (flabby emotion). . . and which have already found moral recognition in some of the rules of the Hague Convention." Some propagandists attacked the nation as a whole. Namier complained that the "talk about stamping out the spirit of German militarism is meaningless. Militarism forms the creed of the German nation and will survive any number of defeats." Despite such attacks, the British were generally careful to make a distinction between that, which was their enemy, and German culture, which was not. Michael Kunczik sees this distinction as aimed at German‐Americans. Mr. Beck declared "In visiting its condemnation [upon Germany], the Supreme Court of civilization should therefore distinguish between the military caste, headed by the Kaiser and the Crown Prince, which precipitated this great calamity, and the ["noble and peace‐loving" and "deceived and misled"] German people.

The Germans rejected this model. .The Kaiser was routinely portrayed as a peace‐loving ruler, despite the image he cultivated as warlord [See Appendix 8], and Germany’s record of having kept the peace for forty years was emphasized. The Germans were not particularly militaristic: "Germany has not created nor unduly fostered militarism in Europe,. . . militarism in Germany forms but a very small part of our general activities, and. . . the maintenance of an army and navy was forced upon us by circumstances." The German people wanted peace but they were all in favor of the war. Dr. Münsterberg claimed "Germany’s pacific and industrious population had only the one wish: to develop its agricultural and industrial, its cultural and moral resources" yet he maintained Dr. Charles Eliot’s contention that the good, cultured Germany opposes German imperialism is proved wrong by the huge numbers of Germans volunteering for the army (over 2,000,000 men). Dernburg echoed the sentiment that it was not just the Kaiser’s war; that it was enthusiastically supported by the people. To prove this, he explained the German system of government, showing that "while the Kaiser represents the Empire in its foreign relations, he may not declare war in the name of the Empire without the consent of the Bundesrat, representing the single States forming the Empire, except when German territory is attacked." Moreover, the Reichstag must pass on war measures, and had done so. In fact, Dernburg emphasized the similarities between the German and American constitutions—both are "a union of a number of Independent States [sic], who have given part of their sovereignty in favor of the Union. He argued the obligation to obtain the support of the Bundesrat imposed a greater check on executive power than did the US constitution and the Reichstag was elected on a more liberal suffrage than was the Congress; therefore, Germans were "as directly and democratically in their Government [sic] as the American people are in theirs." Frank Koester compared the two systems in a statement that probably did not favorably impress many Americans:

The assumption that America has a better form of government or one to which the people are more loyal or with which they are better satisfied than are the German people with the German Government [sic] is highly grotesque. No German, or German‐American especially, having seen the two systems in operation would dream of exchanging the German for the American system.

Koester, who was apparently not a paid German propagandist, went on to claim Germanic superiority in all areas of life over Anglo‐Saxons, including manners: Anglo‐Saxons ate greasy food with their fingers, spit, put dirty feet on chairs and tables, "smoke in the presence of ladies. . . [chew] gum and tobacco in cow‐like fashion" and even Anglo‐Saxon women got drunk; German women did not. Nevertheless, German‐Americans had much to be proud of their fatherland for: in culture, science, industry, and so on. German propagandists were not shy about stressing German advances. They also took great pride in Germany’s military achievements.

Frank Harris took the lead in condemning British society. He condemned its love of aristocracy, "the soul‐destroying influence of this privileged, parasitic, idle class," its libel laws resulting in a society with less free speech than Russia [!], and its soullessness. "There are no ideals in England, no enthusiasm, no high appreciation of art or literature, no impersonal striving. There is absolute veneration for the material standard of value. . . there is nothing but contempt for the spiritual standard of value. . . ." The only hope for Britain was a stunning defeat which would inspire the decent classes of Britain to overthrow their parasitic lords.

German propagandists reminded Americans of how America had suffered at the hands of these British. Koester declared:

[i]n fighting America in 1776 and 1812 the redmen [sic] were treacherously employed, massacring women and children without mercy, from the beginning to the end of each war, just as England employs the fiercest of the savages of the hills of northern India in fighting graduates of Heidelberg and Bonn [two German university towns] on the battlefields of France today."

Koester also quoted a 1797 speech by Thomas Jefferson warning against excessive British influence amounting to domination. Koester also reminded Americans of Britain’s condemnation of the Union in America’s troubles as well as of the 187,000 Germans who served the North, including Custer ("Köster [sic]"). Mr. Dernburg warns that America is functionally encircled by British territories, including Canada, and fleets; that, moreover, America and Germany have always been friends. "We have never had a war, as England had with the United States; never had difficulties such as the Alabama case; the Panama case, and the counteracting of the Monroe Doctrine in the Venezuela business." Münsterberg spoke at the unveiling of a statue to Baron von Steuben in upstate New York and urged "[t]he American nation must maintain its neutrality at any price. It has no right to aid the enemies of Germany as long as it remains loyal to the memory of Washington under whom Steuben fought on this side of the ocean." Koester also appealed to the Declaration of Independence and observed that "America would be a sparsely inhabited dependency of England had England won [the Revolution] and put into effect the measures she adopted against Ireland."

It is not surprising that in a land with as many Irish immigrants as America the Irish question should come into play. Sir Roger Casement, the Irish nationalist leader hanged for high treason in 1916 after returning to Ireland from Germany where he had been soliciting aid, appealed directly to Irish‐Americans.

In this war, Ireland has only one enemy. Let every Irish heart, let every Irish hand, let every Irish purse be with Germany. Let Irishmen in America get ready. . . .Let Irishmen in America stand ready, armed, keen and alert. The German guns that sound the sinking of the British Dreadnoughts will be the call of Ireland to her scattered sons. The fight may be fought on the seas but the fate will be settled on an island. The crippling of the British fleet will mean a joint German‐Irish invasion of Ireland and every Irishman able to join that army of deliverance must get ready to‐day [sic]!

The bloody suppression of the Easter Rising [an Irish attempt to wrest independence from Britain], with British repressive activities in India, turned much US opinion against the British and united Irish‐American groups. The British responded to these controversies by publishing details of a German medal struck to commemorate the sinking of the Lusitania and releasing excerpts of Casement’s diary indicating he was a homosexual. "An English Catholic" wrote a pamphlet trying to defuse the situation. He [she?] admitted past English wrongs to the Irish and claimed England had changed and was now doing right by the Emerald Isle. The author emphasized the Communism of the Citizen Army which joined the Sinn Feiners for the Rebellion. This must have given pause to the majority of Irish‐Americans who were devout Catholics living in an anti‐Communist society. He or she also argued the rebellion was supported by the Germans. It was averred that the rising failed because most Irishmen were satisfied with British rule and the promise of Home Rule, which was interrupted by the war. Besides, England, fighting for her life, had to take stern measures to put down a rebellion fomented by Germany, who would not have been as tolerant beforehand towards either the treachery or the "hostile designs’ of the Irish as the British.

Another sore point of British policy was the naval blockade of ships, including neutral ships, carrying goods, including foodstuffs, intended for the Central Powers. The British tried to rationalize the effects of this starvation policy by citing the involvement of all Germans in the "total war." Robert Lansing felt German propaganda targeted American businessmen suffering from the British blockade. Dernburg argued US trade was threatened by British control of the world’s seas. This would get worse if the German navy was destroyed. This would require the creation of a huge, strong navy. Koester argued that the German fleet was the best protection America had against British aggression. The Germans claimed unrestricted submarine warfare in violation of international law was only a necessary retaliation for the blockade which they accused the neutrals of accepting. American ambassador to Germany James W. Gerard’s response was that the US had not behaved unneutrally and will blame the German government should its navy sink an American ship, and would "take any steps it may be necessary to take to safeguard American lives and property. . . ." Ultimately, those steps included joining the war as an Ally.

12. The First German Race War

In most propaganda campaigns there was a tit‐for‐tat; one side accused, the other responded and launched counter‐accusations. This does not seem to have been the case regarding race. The Germans posed as defenders of the white (i.e. Teutonic) race. The reasons the Germans thought this tack would play in the States, as well as the reasons the British could not reply in kind are clear. Many Americans of Western European descent were concerned about the influx of immigrants from Southern European and Slavic lands and were calling for immigration reform, an effort which came to fruition in 1924. On the West Coast, there was great concern about Asian immigrants, who were first banned in 1882. A new Ku Klux Klan was formed in 1915, combatting not only Blacks but Jews, Catholics, and immigrants. Birth of a Nation was a hit movie.

The Allies could not (even if they wanted to; they may not have) defended themselves in racial terms because they were the ones allied to the Russians, Chinese, Japanese and also the users of African and Asian troops. The British also saw the war as a conflict between Teuton and Slav but did not attach apocalyptic significance the way the Germans did. Of course the probability the Germans believed what they said cannot be discounted. Pan‐Germanism, the belief that all Teutonic people were linked by blood and represented the deserved master race of Europe was a late nineteenth century development and Pan‐Slavism was only slightly older. This was, therefore, the first clash between these two ideologies.

German propagandists played the race card for all it was worth. Professor Burgess referred back to Bismarck, who arrived in Germany in 1871 [sic] and

"imbibed the doctrine that the great national, international and world purpose of the newly created German Empire was to protect and defend the Teutonic civilization of Continental Europe against the oriental Slavic quasi‐civilization on the one side, and the decaying Latin civilization on the other."

The German Government defended its support of Austria‐Hungary in the Serbian crisis by observing that "[I]f the Serbs continued with the aid of Russia and France to menace the existence of Austria‐Hungary, the gradual collapse of Austria and the subjection of all the Slavs, under one Russian sceptre [sic] would be the consequence, thus making untenable the position of the Teutonic race in Central Europe." Dr. Münsterberg called the war between Germany and Russia "moral" because it represented an unavoidable and necessary clash between the two civilizations. Sir Roger Casement warned that Britain, the foe of Europe and European civilization was prepared to betray Europe to the Russians in her pursuit of the destruction of Germany. The Russian/Slavic domination of all Europe was portrayed as the inevitable result of Germany’s defeat (England and France would be too weak to withstand the Russian steamroller). Münsterberg made this point and warned that a triumphant Tsar would "liberate" India and then, somehow, free Canada and Australia. Therefore England was making a grave mistake in fighting Germany.

It was not only the Russians who were racial enemies, the Asian powers and "Native Troops" in the British and French armies were also excoriated. Münsterberg declared

The Americans did not like Japan’s mixing in at the side of England. This capturing of Germany’s little colony in China by a sly trick while Germany’s hands were bound [a stereotypical "Asiatic" practice] had to awake [sic] sympathy in every American. But this was outdone by the latest move of the campaign which has brought Hindus from India and Turkos from Africa into line against the German people. To force these colored races, which surely have not the slightest cause to fight the German nation, into battle against the Teutons is an act which must have brought a feeling of shame for the Allies to every true American.