|

About 20 years ago

, a cousin of mine who had been collecting family histories and doing

genealogy, turned over to me hundreds of pages, copies of her work, family trees and

genealogy forms and interviews, that she felt I might be able to computerize.

It was five or six years before I worked up the courage to even begin looking

through this formidable pile. Browsing through it all, spotting familiar names and some

unfamiliar ones, I was surprised to find one piece of paper. This had events on it I had

never heard of, history I was completely unfamiliar with and characters whose only

connection was an ancestral last name.

Because part of my family is Irish, I telephoned the elderly aunt who had

written this page in 1943, an interview she had had with a great‐uncle, to ask if

this might be Blarney. No. This was the Scottish side of the family. Not into spinning

tales. Nor was my aunt. Definitely lace‐curtain on the Irish side and she assured

me,

#1: the uncle was never a story‐teller and

#2 she had

written down exactly what he had said:

|

|

Two brothers, conscripted off Isle of Skye, Scotland, on English

man of War to America.

Both brothers helped build privatier (sic) Gen. Armstrong War 1812.

They stayed with the ship until wrecked.

|

|

What could this mean? Privatier? Pirates? Like Jean Lafitte or Burt Lancaster in

The Crimson Pirate? My ancestors?

On the other hand, to me, like so many Americans, The War of 1812 was one of

those minor conflicts, ambiguous in outcome. Not WWII or The Civil War. Perhaps

best described as a war between wars: between The American Revolution and

The Mexican‐American War or certainly The Civil War.

Only when I became involved with NYMAS and weekly heard a parade of lauded

historians, authors of dozens of books, authoritative experts and the probing of

primary sources and the re‐spinning of the past, did I begin to take this

seriously.

I'll confess to having started my research, not on computer, but from

some of the dustiest books in the New York Public Library's Research Branch.

But there it was: General Armstrong parenthesis (ship) published as early as

1833.

And within the text, I found almost a lifetime of research, at least for an

inventive history buff:

Here are two references I found within those dusty volumes.

The first records ex‐President Teddy Roosevelt talking to the

book's author from the railing of a ship anchoring in the harbor of a port

on an island in the mid‐Atlantic:

_______

"In there," said the ex‐President, pointing

eagerly as our anchors rumbled down, "was waged one of the most desperate

sea‐fights ever fought, and one of the least known; in there lies

the wreck of the

General Armstrong

, the privateer that stood off twenty times her strength in

British men and guns, and

thereby saved Louisiana from invasion."

My second initial find was a letter by a British eyewitness on shore

during the sea‐fight in 1814:

"After burning the privateer, (Captain) Lloyd made a demand of

the governor to deliver up the Americans as his prisoners, which the governor

refused. He threatened to send five hundred men on shore and take them by force.

The Americans immediately retired, with their arms, to an old Gothic convent;

knocked away the adjoining drawbridge, and determined to defend themselves to

the last. (Lloyd), however, thought better than to send his men. He then

demanded

two men

, who, he said, deserted from his vessel when in America."

Ultimately, I consulted a hundred books plus original documents in

the Admiralty and Foreign Office files at the Public Record Office in the UK, the

National Archives and the Manuscript Division of the Library of Congress, and did

online interviews with descendents of both the American captain and the British

captain. (Incidentally, over all, the event with the General Armstrong seems to be

mentioned in perhaps a quarter of the War of 1812 literature.)

|

|

The facts seem to be these:

The ship The General Armstrong

named after the

Secretary of War, was built in 1812 in a very busy shipyard on New York's East River

by the brothers Adam and Noah Brown. The shipyard was at the end of Houston Street and the

money was put up by Renssalear Havens and other New York investors who would, after

clearance by a prize court, share the proceeds from their captures with the captain, crew,

American Marines and other stockholders. named after the

Secretary of War, was built in 1812 in a very busy shipyard on New York's East River

by the brothers Adam and Noah Brown. The shipyard was at the end of Houston Street and the

money was put up by Renssalear Havens and other New York investors who would, after

clearance by a prize court, share the proceeds from their captures with the captain, crew,

American Marines and other stockholders.

Samuel Chester Reid

was the second captain of the Armstrong, born in Norwich, Connecticut, in 1783, son of a

British Naval officer. The senior Reid was taken prisoner in a night boat expedition at

New London, Connecticut, and afterward resigned his commission to become an American

citizen. At the age of eleven the son went to sea, was captured by a French privateer and

confined for six months at Basseterre, Guadeloupe.

The actual event:

September 26, 1814. Sundown. In the North Atlantic, in the Azores. about 1/3 of the way

between Portugal and the United States in the neutral Portuguese port of Fayal (Faial).

The American privateer, the GENERAL ARMSTRONG, is taking on water and supplies. Three

British men‐of‐war unexpectedly appear, sailing into the mouth of the

harbor. The British commander, Robert Lloyd, irrationally seems to delay his mission

which was to join the flotilla assembling in the Caribbean for the Battle of New

Orleans;

Crews from His Majesty's Ships Plantagenet, Rota and Carnation make two attempts to

board the American ship.

In the first attempt, the British squadron sent boats in to reconnoiter but they were

driven off by American gunfire. Then, at 8PM, four boats (were launched) from

PLANTAGENET and three from ROTA, containing 180 seamen and marines, (and) about

midnight began a major attack, attempting to board the schooner over the bow and the

starboard quarter. The Americans opened fire with long 9‐pounders and a swivel

gun and the boats replied with their carronades. The British failed to cut through the

netting on the quarter as pistols and muskets were fired at them at point blank range

and long pikes were thrust in their faces and they retired to their boats. The attack

over the bow nearly succeeded but Capt. Reid led the aft guard forward and turned the

tide.

The next day British Captain Lloyd ordered HMS CARNATION to close with the schooner

but was kept out of range by the American's single long 42‐pounder gun.

At this point, however, Captain Reid realized that the long term position was hopeless so

he scuttled his ship; he apparently took the 42‐pound swivel gun, pointed it down

the hatchway, and blew a hole in the bottom of the Armstrong. Two Americans had been

killed in the battle and all the rest of the men escaped safely to the Island's

shore.

But the British squadron was seriously depleted in manpower by (depending on the

source) from 75 to 300 sailors and marines and ‐‐ was therefore said to be

late in arriving at New Orleans and this might have had an effect on subsequent history.

|

|

A Famous event:

When the Armstrong's crew returned to the United States, they were feted with

banquets and speeches, up the East Coast from Charleston to Boston.

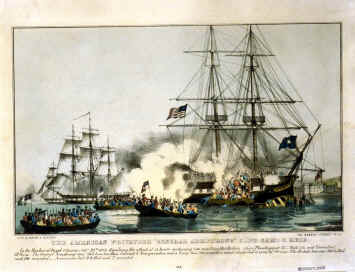

And the story of the American privateer General Armstrong in the Azores became a widely

known subject of illustration, poetry and song in the USA of the 1800s and thereafter.

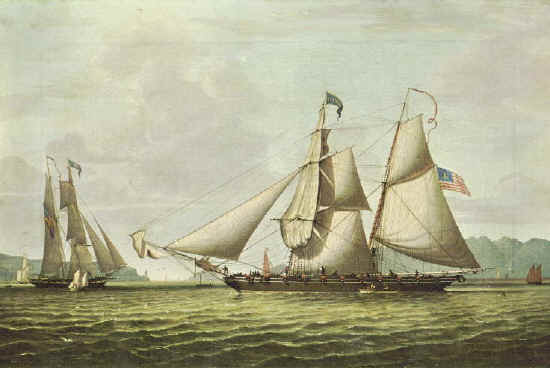

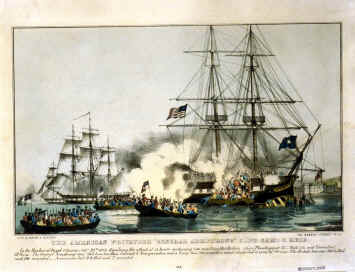

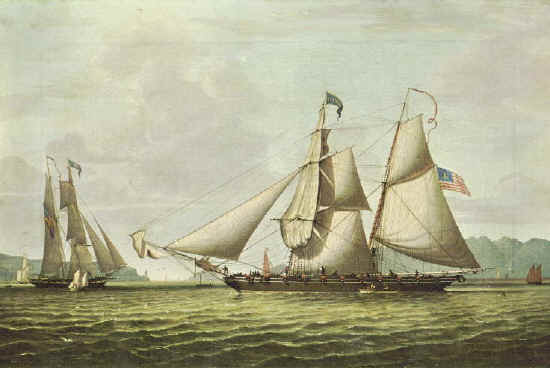

[Currier print]

A hand‐colored Nathaniel Currier print (before he joined with Ives, circa

1830s, from his shop in downtown NYC on Nassau Street. Color done by immigrant

girls, often German with some art education, each one applying a different color

in an assembly‐line fashion. )

[Sheet music from 1843, "The Yankee Boy"]

The fourth from the last stanza reads,

In all of those troubles I had to be there

Imprest and in prison in Battles to share

In the Brig General Armstrong I was in Fayal

Where by scores British seamen had to fall.

A Senate Report published in 1880 concluded:

It is therefore evident that the heroic actions of Captain Reid and his brave

officers and crew saved New Orleans from conquest by England; for had the

British forces arrived even one week before General Jackson, they would have

captured the city, which was then utterly defenseless….

And in 1886, the Cincinnati Inquirer, published a spinoff:

It is therefore incontrovertible that the heroic action of the Armstrong saved New

Orleans from conquest by England; for had the British forces arrived even one week

before General Jackson, they would have captured the city, which was at that time

was utterly defenseless. (Cincinnati Inquirer, Jan, 1886)

Who else says so?

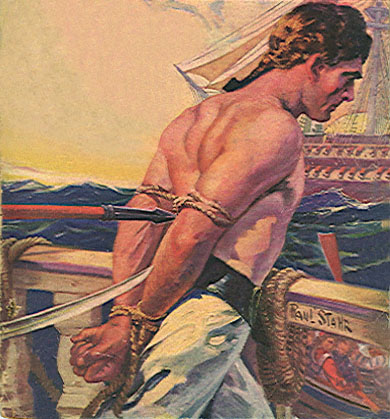

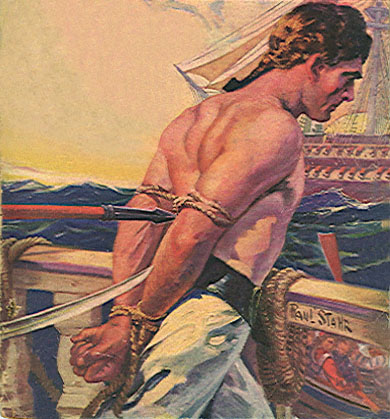

German painter Emanuel Leutze (who also painted "Washington Crossing

the Delaware")

did this rendition of the battle.

Historian John Van Duyn Southworth in The Age Of Sails: war at sea, says

General Andrew Jackson later told Capt. Reid that "If there had been no Battle of

Fayal, there would have been no Battle of New Orleans." Reid had delayed the

British expedition against New Orleans for ten days allowing Jackson to arrive there

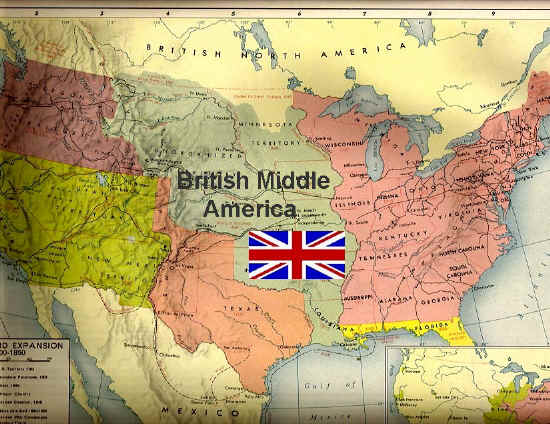

earlier. Thus, Louisiana and the Northwest Territory might now be British if Reid had

not engaged them in what has been called one of the world's most decisive naval

battles.

When a young Teddy Roosevelt wrote his dissertation at Harvard on the Naval

War of 1812, he said:

The British squadron was bound for New Orleans, and, on account of the

delay and loss that it suffered, it was late in arriving, so that this action may be

said to have helped in saving the Crescent City. Few regular commanders could have

done as well as Captain Reid.

But was this merely an incident, now forgotten?

Just so it is clear that this continues down into recent times, if you look up

in Compton's Encyclopedia Online v3.0 © 1998 The Learning Company, Inc.

|

Reid, Samuel Chester (1783‐1861), U.S. Navy

officer, born in

Norwich, Conn.; commanded privateer General Armstrong in War

of 1812; in repulsing a British attack at Fayal, 1814, he

detained British ships

on their way to New Orleans, La., thereby enabling Gen.

Andrew Jackson to make adequate preparations to save the city

|

And this, from the U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 1967 93(11): 157‐160:

|

Abstract of an article

Describes the defense the U.S. privateer General Armstrong

made against a superior British squadron in Fayal Roads,

Azores, in September and October 1814. The Americans

finally had to scuttle their battered ship, but the action

delayed the British squadron 10 days in arriving at Jamaica,

where they were to join the British expedition to attack New

Orleans. Thus the British arrived late at New Orleans, giving

General Andrew Jackson time to set up an adequate

defense of the city. Undocumented, 2 illus.

(bold face by this author)

|

And ultimately, this idea

was carved in stone:

"If there had been no Battle of Fayal, there would

have been no Battle of New Orleans."

[Photos of Reid monument, Greenwood Cemetery, Brooklyn]

|

|

The speculation:

So I laid out the three lines from my aunt and all this accumulated

information I had found and it started to make sense. "If there had been no Battle of

Fayal, there would have been no Battle of New Orleans."

Well, with that kind of logic and a hefty admixture of speculation and

imagination, I began to imagine a sweeping drama. A friend suggested my ancestor could be

played by Mel Gibson with Charlie Sheehan as his brother. As for British commander Lloyd,

what a great, villainous role for Charles Laughton if he were still alive, or today

perhaps an even better role for Anthony Hopkins at his Hannibal Lector best.

This drama would perhaps begin at a moment in time when a dirty look by an

impressed Scotsman named Mackie, my ancestor, evolves into a string of circumstances

ending with the collapse of British hopes for empire in the Western Hemisphere and with

the rise of the American nation.

Without the details and spun from my aunt's brief notes, I began to

imagine, obviously more as fiction than as history, a scenario where

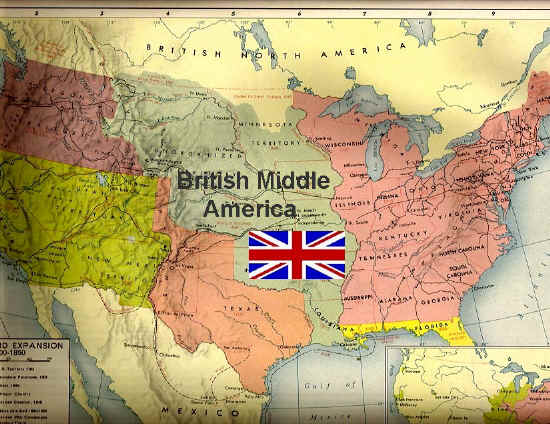

Click on the

map for a much larger image

[Speculative MAP]

-

The brothers, while fishing off the coast of Scotland, are taken and

impressed into the British Navy

-

They end up on Captain Lloyd's ship, (possibly the Guerriere

which was defeated by the USS Constitution very early in the War)

-

They are either among the prisoners in Boston or they jump ship,

possibly off the coast of Virginia or in Long Island Sound

-

Make there way to NYC, get jobs as ship fitters building the General

Armstrong with Noah and Adam Brown at the end of Houston Street on the East River

-

Sail with the General Armstrong on its many voyages

-

When British Captain Lloyd sails into the harbor in the Azores and

sees the General Armstrong, he spies the Mackies aboard. In a brief moment, as the

Plantagenet glides past the Armstrong, Lloyd loses his mind, swears to avenge their

desertion and to retake his former crewmembers no matter what…

I imagined entitling all this "Twist of Fate"

The questions:

Was it true? So while my curiosity about my ancestors, typical of

genealogical pursuits, was egotistical, self‐centered and vanity‐driven, the

subsequent questions this led to are perhaps of historical interest:

-

Why did British Captain Robert Lloyd attack the Armstrong when he had

other orders and despite being in a neutral port?

-

Did the attack really delay the assembly of the British expedition

against New Orleans?

-

Did the delay, as so many historians have asserted, really cause the

British to lose the Battle of New Orleans?

-

If the British HAD WON at New Orleans, would they have ignored the

Peace Treaty of 1814 and ruled the middle of America?

And if my ancestors, the General Armstrong, Reid, or Lloyd didn't delay

the British from starting the Battle of New Orleans, WHAT DID?

I will not be able to answer all these questions. Besides,

'what‐if' is not history. But examining them, I've found, reveals a

rich history of the Making of America and some examples of what research into primary

sources can reveal. I'd like to share some of this examination with you.

|

|

First, let me give you some background on the history and causes of the

War of 1812 and give some detail on Privateers and on Impressment:

A Short History of the War of 1812

The United States declared war on England in June of 1812. President James

Madison and the US Congress, especially southern and western representatives, felt it had

been treated with contempt by England and the cry was "Free Trade and Sailors'

Rights"

-

It was Free Trade versus Great Britain's Orders In Council

which required US ships to stop at a British port and get a license to trade on the

French‐dominated Continent ‐ a measure the British had taken as part

of the long and ongoing Napoleonic Wars.

-

It was Sailors Rights against Britain's impressment of

American seaman into the Royal Navy.

Though not a stated war aim, the conquest of Canada was a big factor.

Westerners and Southerners backed it. There were 5 attempts to do it. And none of them

worked out. Even tho Thomas Jefferson had said that the annexation of Canada to the US

"was merely a matter of marching." There were plenty of disappointments.

It's not easy to characterize the War of 1812. Let's say that if

the transatlantic cable had been operational 44 years earlier, this war might not have

begun at all, and it certainly wouldn't have ended as it did.

It was a war of disconnects, and of surprises.

For example:

-

A key cause, the squelching of free trade by the British

‐ The Orders In Council, were suspended in London just 3 days before the US

Congress declared war. We just didn't know it.

-

This is a war in which the Royal Navy outnumbers the US

almost 100 to 1. And yet London shipowners are begging for protection from

American ships‐in the Irish Sea and waters around the UK! And that, of

course, is where American privateers will come in.

-

This is a war in which an army gets to take and burn the

other side's capital city, Washington, DC. But it doesn't make much

difference.

-

Militarily, four of Britain's best, most

experienced generals, are killed on the field of battle on American

soil.

-

The most glorious land battle, at least to the

Americans, was fought over two weeks after a treaty of peace was signed: that is,

the Battle of New Orleans.

-

And after the Battle of New Orleans, the British go on

to take a key U.S. installation, the installation in Mobile Harbor which, if taken

on their first attempt two months earlier, probably would have led to a British

victory at New Orleans.

-

Before the year 1812, the United States could have as

easily have gone to war with France. Pickering claims that in 1795 alone the

French captured 316 American ships.

(cited in The Quasi‐War: The Politics and

Diplomacy of the Undeclared War with France 1797‐1801)

I'll shortly get to the very important issue of impressment, but

after extensive examination, I'd say that perhaps behind every war is national

attitude and nothing could be more true of the War of 1812:

British attitudes toward America

"First, it should be said that the entirety of the War of 1812 was very

small change in British minds; in London the real problem was Napoleon, not a gaggle of

far‐off and half‐baked ex‐colonials with an attitude."

(MARHST‐L)

After the war of 1812, an American was upbraiding an Englishman for his

ignorance of events: The American asked "Did you know that the British burned

Washington?" "No." said the Englishman, "But I know we burned Joan of

Arc."

Vice Admiral Sir Alexander Cochrane, British

commander‐in‐chief during the attacks on Washington and Baltimore and naval

commander of the expedition to New Orleans, wrote of the Americans, "They are a

whining, canting race much like the spaniel ‐‐ and require the same

treatment‐‐(they) must be drubbed into good manners." (Christopher

T. George) Quoted in Walter Lord, The Dawn's Early Light. New York: W. W. Norton,

1972, 35.

Possibly his hatred of Americans had a personal origin: his elder

brother, on October 17, 1781, had been standing next to Cornwallis at Yorktown, when his

head was shot off by an American cannonball. (Christopher T. George) We'll hear

more about Admiral Cochrane as he leads the naval expedition to New Orleans, which Lloyd

is to join.

Perhaps the most stunning event was the burning of Washington; but this

event has perhaps more to do with the needs of American patriotic feeling than strategic

necessity. Now, the British usually pass it off as payback for American burning of York in

Ontario. (York, it should be noted, is now Toronto.) However, the US soldiers had run amok

at York and that burning was against orders. But Washington was burned according to

orders and the London Statesman said, "The (KAH‐sacks) Cossacks

spared Paris but we spared not the capitol of America." and were joined by

some Members of Parliament. (Hickey). But when the news of the burning of Washington

reached London, there were celebrations and bonfires in the streets.

Now, in military history in general, if you capture your enemy's

capital city, you win the war; does that mean the capture of Washington D. C. meant the

British won the War?

Except for a few big, government buildings, Washington was a small town,

parts still swamp. Simply, it wasn't Moscow, Paris or London. The Government had only

been there for 14 years and congressmen called it "wilderness city," or

"Capital of Miserable Huts". There had even been talk of moving the Capitol.

But the burning became important in the American mind. Perhaps even more

important was:

Impressment

For America and American pride, perhaps the biggest single cause of the War

of 1812 was impressment. The Royal Navy, just between the years of 1803 and 1810, had

taken at least forty‐five hundred American sailors from US ships; students of the

Jeffersonian administration will know of the USS Chesapeake incident in 1807 where

the Royal Navy forcibly took four sailors off a US Navy vessel and ended up hanging at

least one of them. know of the USS Chesapeake incident in 1807 where

the Royal Navy forcibly took four sailors off a US Navy vessel and ended up hanging at

least one of them.

Now, in all this, my ancestors would not have been among the more

than 6,000 Americans wrongly impressed into Royal Navy floating hells. As British

subjects, they would have been rightly and legally impressed into Royal Navy

floating hells.

During the peacetime that preceded the Napoleonic Wars, the Royal Navy had

about 10,000 men; by the War of 1812, the number had risen to 140,000. The overwhelming

majority of these men came from The Press. To maintain the navy's strength,

the press gangs were constantly at work. Not only did they have to replace men who were

killed or died in service, but they also had to replace the countless vacancies created by

desertion. Lord Nelson estimated that between 1793 and 1801 perhaps as many as 40,000 men

deserted the navy.

The British also boarded hundreds of American ships on the high seas,

hauling off droves of their own sailors who had deserted to the growing American merchant

fleet, which offered better pay and conditions. During a six‐year period through

1810, the more than 4,500 sailors the British snatched off American vessels, included

1,361 native‐born Americans, who were later freed with few apologies.

Madison's report to Congress, recommending war, said,

Under the pretext of impressing British seamen, our

fellow‐citizens are seized in British ports, on the high seas, and in every

other quarter to which the British power extends, are taken on board British

men‐of‐war and compelled to serve there as British subjects. In this

mode our citizens are wantonly snatched from their country and their families,

deprived of their liberty, and doomed to an ignominious and slavish bondage, compelled

to fight the battles of a foreign country, and often to perish in them.

Any English‐speaking sailor was in danger of being impressed.

Especially with a Scottish, Irish or English brogue. But it was all problematic because 25

years before, all Americans were English citizens. Until 1850, England did not

recognize the right of a man to renounce his nationality.

A case is reported where a Royal Navy captain listened to the protests of

a newly impressed sailor who claimed he was an American. The Captain looked down his

nose, "Why, you're nothing but a Scotsman!" (Durand)

During the War, 23 American prisoners of war claimed by Britain as its

subjects, some of whom had been naturalized in America, were sent to England for trial as

traitors, leading to threats of retaliation. The issue was resolved by stipulation in the

agreement of 16 July 1814 on the exchange of prisoners.

The US Government instituted Seamen's Protection Certificates beginning

in 1806 but the English said you could buy papers in any American port for a dollar.

And with the war against Napoleon, the Royal Navy was hungry for seamen.

Let me quote here the tail‐end of the story of the General Armstrong

in the Battle in the Azores; this is from a recounting done by the American

consul‐general on the island:

"Since this affair, the commander, Lloyd, threatened to send on shore

an armed force, and arrest the privateer's crew, saying there were many Englishmen

among them. …... At length, Captain Lloyd, fearful of losing more men, if he put his

threats in execution, adopted this stratagem:

He addressed an official letter to the Governor, stating that in the

American crew were two men who deserted from his squadron in America, and as they were

guilty of high treason, he required them to be found and given up." (Cogg / JOHN B.

DABNEY)

This was at a time when commanders of British warships patrolled the

Atlantic, short of seamen in their own ships, pressed American merchant seamen into

service. When boarding a U.S. ship for inspection, British officers frequently demanded a

muster of the ship’s crew in order to search for deserters.

This could have happened to my ancestors….

My ancestors and their crewmates might have been under just such a threat.

I've speculated that they may have changed their names for this reason and therefore

I could never pinpoint them in documents. But at least ‐‐ it's the

instigation for this pursuit in history

In Scotland, during the Napoleonic Wars, impressment was taken with

anguish but inevitably for granted. The Royal Navy press gangs ashore might do their

"recruiting" in daylight or at midnight at the local pub. But my ancestors as

fishermen would have definitely been 1‐A in the regulations called "Who the

Gang might Press". In Scotland in this era, some towns tried to mitigate the

randomness of the pressgang by having town elders confer and then offer up young men

without family obligations so the town wouldn't have to support the families of

pressed men. Here, of course, are the beginnings of The Draft Board.

According to Jerome Garitee's great book on privateering from

Baltimore, The Republic's Private Navy, American citizenship was required to

join the crew of an American privateer. All carried Seamen's Protection Certificates

‐ if one were found falsely issued, it would confirm the British presumption and

imperil the POW status of the entire crew.

My surmise is that my ancestors were "hot potatoes" as

un‐naturalized Scotsmen on the General Armstrong. If captured they may have been

identified by a British officer who would then use his discovery as a pretext for

grabbing many more sailors. For the Scotsmen, the penalty was not just

re‐impressment but hanging for desertion and high‐treason. If they had

papers, legitimate or otherwise, they may have flung them overboard. Or they may have

taken assumed names from the beginning.

Let me quote here A British/Canadian Perspective (Galafilm)

Sea power was Britain's pride and glory, and it was imperative to

its defense. In the early 1800s, Britain was engaged in a life‐and‐death

struggle with the Napoleonic Empire, and the Royal Navy was the only thing that

prevented Napoleon from crossing the Channel and conquering Britain.

Despite the navy's acute need for sailing crews, thousands of

British seamen chose to jump ship in favour of a more comfortable and profitable

position with the American merchant marine.

Wartime necessity justified the recapture of "deserters" from

any ship. Even deserters who had adopted the American nationality were not immune from

seizure as the Royal Navy adhered to a principle of inalienable British citizenship.

Besides, American citizenship certificates were frequently assumed to be forged.

An American Perspective

The British Royal Navy was a notorious floating hell. The pay was low,

when it was paid at all, shipboard conditions were miserable, and there was the

ever‐present risk of death or injury in battle. Small wonder then, that so many

British sailors chose to abandon the Royal Navy for the rapidly expanding American

merchant marine, which offered better pay and better conditions. ….and once the War of

1812 began, if a deserter could get on the crew of a fast American privateer and share

in it's prizes, why that would be going from Hell to Heaven.

When British commanders began to board American ships in search of Royal

Navy deserters, the Americans were highly offended. First of all, searching an

American ship was an insult to national sovereignty. Secondly, legitimate Americans

were sometimes "impressed" into British service on the pretext that they

were British deserters. As there were no obvious differences in physical appearance,

language or clothing, the British Navy was able to abduct as many as 6,000 Americans

in the early 1800s.

Again, the cry in the US was "Sailors' Rights and Free Trade"

with the human emphasis on Sailors' Rights ‐ that is, freedom from the threat

of impressment.

Now, as to the Heaven an impressed sailor could escape to …………

|

|

Privateers ‐who were they in military

history?

At the beginning of the War of 1812, the American Navy consisted of

about 16 major vessels, having in all 442 guns.

By contrast, the Royal Navy, tho focused mostly on Napoleon, consisted

of over 1,500 vessels of war. It was a Navy with 30 continuous years of conflict

behind it.

But during the fall and winter of 1812‐13, American privateers,

swarming the Atlantic, captured 500 British vessels.

Many people use the words pirate and privateer interchangeably but they

are not the same thing.

|

Navy

|

Privateer

|

Pirate

|

|

Was the government's seaborne force

|

Had government authorization ‐ a business venture

|

Independent

|

|

Destroyed, and sometimes captured the enemy

|

Captured declared‐enemy's ships

|

Captured targets of opportunity

|

|

Took & shared prizes too but not first priority

|

Split with the government

|

Kept it all

|

|

In war or peace

|

Only in war

|

In war or peace

|

|

Fought under its true flag

|

Never fired a gun under false colors, tho might approach with

one.

|

Usually fired a gun under false colors

|

A pirate was an individual who acted on his own, rather than in the

interests of a particular nation, and attacked almost any vessel on the seas for

his own gain, while a privateer usually acted for a specific country when that

country was at odds with another.

The privateer was used as a tool to economically and militarily hurt

another country. They were granted Letters of Marque, a license to attack enemy

ships without retaliation from the issuing country.

Simply, a privateer is a privately financed, owned, outfitted,

crewed, and operated armed vessel ‐‐ a private warship

‐‐ allowed forth under government license to attack the vessels of a

declared national enemy, for profit. Thus, unlike pirates, who are simply

criminal, privateers are quite legitimate. Also, their activity must cease with

peace; anything further indeed is piracy, and so recognized internationally.

Because the United States began the War of 1812 with 16 Navy ships,

the enlistment of 1,400 additional fighting ships ‐ privateers‐ by

War's end was important. There were complaints that the appeal and potential

profit of privateer service made it more difficult for the US to enlist crew in

the regular Navy but under some circumstances, the US Navy also took and shared

prizes too.

In New York City, what the dot.com business was to 1999, privateering

was to 1812

It was Patriotism AND profit ‐ sometimes big profits. A number of

investors could put up perhaps $40,000 (1813) dollars to build and arm a sloop (figure

$1.5 million today). The average prize proceeds were $116,712 per privateer (although

the privateer America took $700,000 = perhaps a hundred million today)

Here was a thoroughly incentive‐based system. After the US took a

portion, officers and crew generally received one‐half of all the proceeds

generated by the sale of captured ships and their cargoes, the other half was

distributed to the investors.

[Armstrong stock certificate]

Since most crewmen earned from two to four shares, this meant that in

the typical privateer cruise of three months, a man might earn the equivalent of

eighteen months' wages, and sometimes even more (Garitee 1977, 193‐94).

On the other hand, some privateers captured little or nothing or were

captured or destroyed themselves.

There's a wonderful paper by a Texas economics professor,

Larry J. Sechrest, on the web called Naval Warfare for Private

Profit. In it, he says,

Privateering was not a worthless anachronism. It was a

powerful method by which maritime nations could discourage aggressors without

indulging in the massive public expenditures needed to maintain a large public

navy. Indeed, it was, on occasion, publicly acknowledged to be more effective than

public navies.

In addition, since the British blockade and war in general had reduced

US imports to 10% of their pre‐war total, the captured English merchant ships

that the American privateers sent into NY, Baltimore, Charleston, etc., brought scarce

supplies to the American economy.

The war lasted about 31 months, a bit short of three years; in that

time, American privateers took some 1,800 British merchantmen, an average of about two

per day, 60 per month, and at times brought vital British sea trade to a virtual halt.

There was a time when British soldiers in the Peninsula Campaign in Spain were not

paid because of American privateers.

To show that everyone wanted to get into the business, I found at the

National Archives what looked like a Letter of Marque for a large rowboat. Sure

enough, I later found a record of an English merchantman with $20,000 worth of goods

on board, which was captured off George's River, by a row‐boat privateer,

and sent into a neighboring port. (Cogges)

Privateering goes back a log way. "by mid 1700s [privateering] was

carefully regulated, respectable and as law abiding as the navy," according to

Daniel Conlin, Curator of Marine History at the Maritime Museum of the Atlantic in

Halifax, Nova Scotia.

The British had privateers. So did the French and the Canadians. One

Canadian privateer waited off Cape Cod to snatch American merchantmen coming from

Boston.

It was not enough to build and outfit a vessel for privateering

activity, one also had to post a bond in order to guarantee compliance with

international laws of the sea. The intent was to make sure that privateers did not

degenerate into pirates. Such "letters‐of‐Marque" or

"surety" bonds were usually in the amount of either $5,000 or $10,000

Again, what distinguished a privateer from a pirate was its license, its

Letter of Marque.

[Letter of Marque] authorizing James M. Mortimer Captain, and William

Ross Lieutenant of the said schooner Patapsco and the other officers and crew

thereof

to subdue, seize and take any armed or unarmed British vessel, public

or private, which shall be found within the jurisdictional limits of the United

States or elsewhere on the high seas, or within the waters of the British dominions

, and such captured vessel, with her apparel, guns and appurtenances,

and the goods and effects which shall be found on board the same, together with the

British persons and others who shall be acting on board, to bring within some port

of the United States;

I should also add, since we will later focus of those events leading up

to the Battle of New Orleans, regarding Pirate vs Privateer:

The famous Jean Lafitte and Dominique You were indeed pirates, that is,

high‐seas criminals, who, by fiat of Andrew Jackson, became, at least for a

time, not privateers but allies of the United Sates at New Orleans, primarily for

their artillery skills and their stocks of munitions. Lafitte, however, was back to

his old tricks in the Gulf of Mexico before long, as a pirate. (rr)

It should be noted that privateering is not necessarily a dead concept.

It still stands in the US Constitution, in the very same breath as the right to

declare war:

Article I, Section 8 of the Constitution states,

"The

Congress shall have power ... to declare war, grant letters of marque and

reprisal, and make rules concerning captures on land and water;

Let's talk about how they did that ……

|

|

[Privateers at war]

Technology

and armament in 1812

"Profit‐minded Americans had created a type of vessel especially well

suited to commerce raiding. It was a sort of schooner with ship or brig rigging. It had

speed and an uncanny ability to seemingly sail up

wind. When heavier British vessels were closing in on it, they were often astounded to

see it virtually head into the wind and outrun them. It carried 16 to 18 guns and 90 to

150 sailors. It did not fight warships unless cornered, but outran them. On the other

hand, it could outmaneuver and outfight armed merchantmen. Royal Navy men of war

depended on largely sailing down wind. ability to seemingly sail up

wind. When heavier British vessels were closing in on it, they were often astounded to

see it virtually head into the wind and outrun them. It carried 16 to 18 guns and 90 to

150 sailors. It did not fight warships unless cornered, but outran them. On the other

hand, it could outmaneuver and outfight armed merchantmen. Royal Navy men of war

depended on largely sailing down wind.

The power that made all this happen, of course, was the wind. And it was

American perfection of a sailing ship that could make the most of the wind that

made her so surprisingly formidable.

These small, lightly armored schooners, built in Boston and Charleston

and especially in New York and Baltimore, were continuously perfected in design with

two objectives:

-

to get in fast, even into the middle of a British convoy, threaten

and then board an English merchantman and

-

to get away fast, outrunning the Royal Navy's strongest

men‐of‐war and the range of their longest guns.

In order to be fast, they had lots of sail, especially in relation to

their weight and size. If you look at a Royal Navy square‐rigger, you could see

that only wind from the rear or a rear angle could propel her forward. This wind

factor also had a lot to do with maneuverability. The Royal Navy was thinking of

gigantic gun‐platforms, the kind that would win for Nelson at Trafalgar.

The shape and arrangement of sails on an American privateer

schooner, brig or brigantine, are quickly movable to much more radical angles. English

seamen have written that they saw privateers escaping "sailing directly into the

wind."

The armament of these private armed vessels reflect their tactics. Unlike

the RN's gun‐platforms, a privateer needed only enough armament to

intimidate a lightly‐armed merchantman. The intent was never to face a ship of

the British Navy and win a gun battle. So the privateer would have 6 to 20 cannon on

each side and one or two "Long Toms". Because she was more maneuverable,

sailing so that the guns pointed in the right direction was something she could do

better than a man‐of‐war. (rr)

Of course, all this took place at speeds 2 to 20 miles per hour; it would

have seemed like magical slow motion if we had been there. (rr)

"General Armstrong', one of the most famous American

privateers, carried 8 long 9‐pounders, 1 long 42, and 90 men. She had taken $1

million in English property when cornered in September 1814 in the Portuguese port of

Fayal by 'Rota' and 'Plantagenet.'

This is not to say that American privateers were on an uninterrupted

course of triumph: human error and miscalculations intervened. Britain did an early

Q‐ship, disguising a well‐armed brig as a merchant ship and waited for

an American privateer to try to pounce. But, there are celebrated cases of the

privateer coming out on top, even in these circumstances.

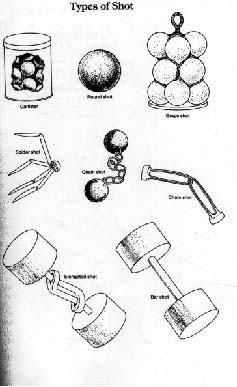

In this age of sail, it took some guts to engage in these showdowns. The

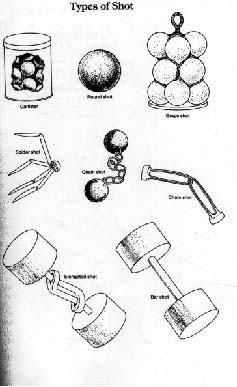

munitions were daunting and naval science of the day often measured the effectiveness

of a vessel of war in the weight of objects like these a ship could throw at an enemy:

The devices at the bottom were intended to bring down whole masts while

the nasty looking spider device in the middle was meant to tear sail,

all depriving the privateer's prey of its power.

[Instructions]

I also tried to determine how bloodthirsty and ruthless these

non‐pirate privateers were. George Coggeshall who wrote A History of the

American privateers and was himself a privateer captain, goes to great pains to

describe the gentlemanly‐behavior of these warriors:

These are instructions issued along with the Letter of Marque:

…2. …rights of neutral powers…You are particularly to avoid even the

appearance of using force or seduction

…3. Toward enemy vessels and their crews, you are to proceed in

exercising the rights of war,

with all the justice and humanity which characterize

the nation of which you are members….

EXTRACT FROM THE LOG‐BOOK OF THE SCHOONER HIGHFLYER, OF

BALTIMORE.

The Dolphin has taken six prizes without receiving the

smallest injury. She was repeatedly chased by the English, and at one time for

twenty‐four hours, but finally escaped.

She has treated her

prisoners with the greatest kindness. In rowing away from

men‐of‐war, she found great aid from their voluntary assistance. The

prisoners said they had much rather go to America than return on board a British

man‐of‐war."

|

|

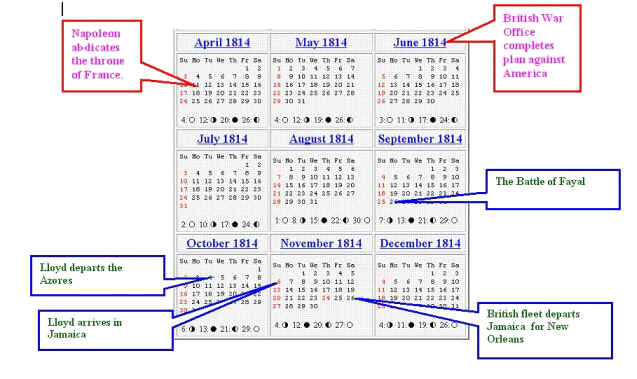

For America, for privateers, for the Royal Navy, and for New Orleans,

perhaps

The fateful year was: 1814

August may have been the peak month of the War.

And a month in which many forces were at play

If you were there then, you probably would never have guessed

that the War would be over in six months or that the US wouldn't have

completely lost it and maybe its independence. Here's what I mean:

In August, British Navy ships ‐ from all over ‐

began their voyage to the rendezvous point in the Caribbean. Capt. Robert Lloyd

would have set sail from England.

The Battle of New Orleans

New Orleans might be thought of as the southern prong of a

3‐pronged attack decided on by the British in the Spring of 1814, just as

Peace negotiations were getting under way. What we'd call today, "Combined

Operations"

To bring the American nation to heel, the British cabinet worked out a

grand plan of conquest. The goal was "to destroy and lay waste the principal

towns and commercial cities assailable either by their land or naval forces."

The strategy consisted of a three‐pronged invasion from three widely

separated areas of the continent: an amphibian thrust into the Chesapeake Bay area

aimed at Washington, Baltimore, and other coastal cities; another from Montreal into

New York State via Lake Champlain; and a third from the Gulf of Mexico into

Louisiana with the purpose of seizing New Orleans and detaching the Mississippi

Valley from the Union.

But the biggest, best prize was to be New Orleans. Admiral

Cochrane's fifty‐ship armada initially carrying fifteen hundred

marines and 5,498 veteran troops sailed from Negril Bay, Jamaica. Other

units joined them near New Orleans.

Morale was high. So high that at Cochrane Hqs at Jamaica, the

New Orleans target was discussed in front of outsiders with US connections and

Cochrane's log records that it seemed the whole Island knew.

The New Orleans objective, in some ways, was no secret from the

start. In London, thruout the war, many allusions were made to this city as a

valuable prize.

There was an image in the British mind of the French, Spanish,

and Creole citizens of New Orleans being alienated from their new American

rulers. The Louisiana Purchase was only 15 years before. Statehood took place

just 45 days before the outbreak of the War.

My main concern here was not with the land Battle of New

Orleans but rather the expedition. How it was planned, how it assembled. What

actually happened as it progressed. Did the fight with the General Armstrong really

delay the assembly of the British expedition against New Orleans?

Some conclusions

Now I was in a position to deal with some of the questions which

initially arose.

Why did British Captain Robert Lloyd attack the Armstrong when he

had orders to join the New Orleans expedition and despite being in a neutral

port?

In addition to all my fascination with the prospect that my ancestors

were on the General Armstrong, I also became deeply intrigued with Robert Lloyd, the

British captain who commanded the squadron that sailed into the harbor in the Azores

that September evening.

He was under orders. Important ones. For the big strike at the

American underbelly.

But here was possibly a Captain on‐the‐edge. Perhaps he

had been viewed like numerous British captains who had risen thru the ranks: one

Naval observer complained about the "means of bringing persons of obscure birth

into undue distinction," ‐‐ many sailors made their fortunes and

ranks through the capture of enemy ships.

HMS Plantagenet in three months captured 25 small American ships along

the NE coast.

I found four other intriguing events which have been recorded

as having occurred while Lloyd commanded the Plantagenet:

1. The London Statesman, in 1813 published an article which

seemed to imply that Lloyd had failed to pursue an American warship off the coast

of Maryland.

2. During most of the war, the USS Constitution was bottled up in

the Chesapeake. In an attempt to clear the blockading British ships, Edward Mix of

the US Navy attempted to target the Plantagenet with the world's first use of

"fish torpedoes" ‐ that is, a submarine. The explosion took place

within view of Lloyd's ship. (Forester)

Really intriguing but without a full explanation was a recorded

incident where

3. During a hit‐and‐run attack from British blockaders

along the Connecticut coast where HMS Plantagenet stood "on the American

station", five Englishmen were captured by local militia. They gave their

"parole", that is, their word they were out of action for the duration

or until exchanged. They were discovered back in action shortly thereafter. One of

the ‐ apparently ordinary seamen, marines or junior officers ‐ had

given his name to the militia as: Robert Lloyd. (History of Stonington).

4. When Lloyd arrived at Jamaica, he sent a letter to Admiral

Cochrane, asking for a court‐martial. I made great effort to follow this up

and failed. Did he want to clear his name over the Battle of Fayal and the loss of

so many men?

Were this drama, we could build a wonderful villain.

Herodotus, known for his double roles as an historian and

a spinner of yarns is supposed to have said ‐ referring to events in history

‐ "Very few things happen at the right time and the rest do not happen at

all. The conscientious historian will correct these defects."

Now, as I looked over these materials, doubts began to creep into my

speculations.

Some Doubts

Before, I showed a hand‐colored Nathaniel Currier print

But this illustration betrays a number of inaccuracies:

-

In spite of the sky, all accounts agree that the battle was fought

after dark and the multiple boat attack after midnight.

-

The legend inscribed below has the date in October ‐ wrong

by a month.

-

Also, The General Armstrong was not a square‐rigged vessel.

And remember the 1886 Cincinnati Inquirer piece I

quoted?:

It is therefore incontrovertible that the heroic action of the

Armstrong saved New Orleans from ….

-

Fine, except that this article had the British arriving at New

Orleans direct from Waterloo,

though that actually happened 5 months

later,

-

and it talks about Lord Castlereagh as British Prime minister,

when he was actually Foreign Secretary.

So despite all the 19th century hype and the readiness with

which a number of sources have credited The General Armstrong with having delayed

the invasion and assured American victory, I have hopefully cast a skeptical eye on

this.

|

Did Lloyd's attack on the General Armstrong really delay the

assembly of the British expedition against New Orleans?

As I thought about it, it occurred to me: Why should it? Lloyd had

only 3 ships out of 50 in the expedition?

Now, it is true that it could take 8 or 10 weeks to get from

Plymouth to Jamaica.

Westerly voyages took longer, the Gulf Stream was against

you…sailors called it "sailing uphill". He might have run into autumn

storms and hurricanes

It's worth noting that British morale was high in Jamaica before

they left for New Orleans. Higher officers wives accompanied them. The New Orleans

objective was referred to as "Booty and Beauty

". The Beauty for the doe‐eyed Creole girls

and the Booty for the New Orleans warehouses

full of cotton and perhaps $15 million worth of goods. The British Treasury and

economy were broke. A threatened renewal of the property tax had awful political

implications. (Perhaps another theory and another paper, or perhaps just a

contributing factor?)

General Packenham, the Army commander, didn't arrive until the

fleet was at New Orleans meaning they started from Jamaica without him.

This told me a lot about cross‐Atlantic movement: British

General Edward Packenham was appointed to command the land forces and work with

Admiral Cochrane, who was in Jamaica. He was to replace General Ross who was

killed by American riflemen outside Baltimore after the burning of Washington.

Word of this needed‐change didn't reach London until

mid‐October and Packenham was appointed on October 24th and

departed Plymouth on October 28th with General Gibbs, to be his second

in command. (They were both to die, like Ross, shot by American marksmen.)

On their voyage to join the New Orleans force, the elderly

Captain of HMS Statira (STAH‐tir‐ah) shortened sail every night.

The passengers urged him to make all possible speed. But the captain is the

captain. (Brown)

They were 7 weeks to get to Jamaica. Cochrane's fleet had left.

Packenham and Gibbs arrived at New Orleans on Christmas Day, after the first

actions with the Americans.

So Packenham was late. And that, truly, may have effected the outcome

of the Battle of New Orleans.

Did a delay, as so many historians have asserted, really cause the

British to lose the Battle of New Orleans?

The evidence clearly suggests that if the British had arrived at New

Orleans earlier and moved more quickly, the city would have been theirs. Here the

answer is probably yes.

One interesting speculation relates to a letter written by Wellington

after the war, charging that British Naval Commander Cochrane advocated the project

against New Orleans for the purpose of plunder (that estimated $15 million in cotton

and goods in New Orleans' warehouses) and then led the army through Lake Borgne

into a trap. Combine this idea with several recorded complaints that the British

expedition had numerous transports heavy with ballast which traveled slowly to the

rendezvous in Jamaica: Ships loaded with ballast in the expectation the ballast

would be replaced with the booty of New Orleans. Wellington was saying that the

Royal Navy, in its quest for its own prizes, for greed, got his

brother‐in‐law killed.

We've also heard from John Buchanan about Jackson and Horseshoe

Bend ‐ ‐

Had the Creek civil war been delayed and

synchronized with the landing of the British troops, the combined forces might well

have overcome Jackson's army and gone on to capture New Orleans and the lower

Mississippi Valley.

But my research brought me back to a more basic, simple question

‐

When did the British Navy plan to rendezvous to attack New Orleans?

This was a big operation. More ships than at Trafalgar.

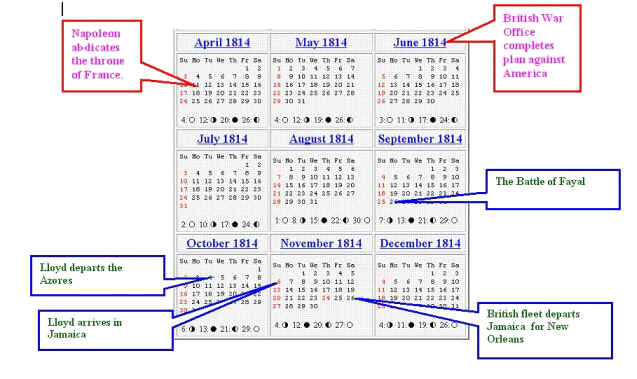

My great discovery was the original War Plan ‐ written in

London in the Spring ‐ and dated 20 June 1814:

|

|

"…should meet

at the said rendezvous not later than the 20th of

November."

"…should meet

at the said rendezvous not later than the 20th of

November."

|

|

So as far back as June, the planned rendezvous date

was set to November 20th This date was never changed; subsequent documents

emphasized that these instructions were firm . The advantage Jackson had,

in addition to good intelligence, was simply that the long‐before planned

date was set

so late

. The British, in fact, did complete the rendezvous

by November 20th and departed Jamaica for New Orleans on November

26th, including Lloyd and the ships that had fought the General

Armstrong in Jamaica two months before.

But the final blow to the contention of so many historians, and of

Andrew Jackson, Teddy Roosevelt and the U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings,

(not to mention my fantasies about the impact of my

ancestors)

came when I finally saw the log of Royal Navy Captain Robert

Lloyd's ship, the Plantagenet.

In fact, it shows him leaving the Azores on October 5th,

eight days after the battle.

But even more importantly, it shows him arriving at Port Royal, just

outside Kingston, Jamaica just one month later, on November 4th,

In plenty of time for the Battle of New Orleans,

in complete contradiction of the American legend.

In other words, LLOYD WASN'T LATE! In fact, he

was early!

If the British HAD WON at New Orleans, would they have ignored the

Peace Treaty and ruled the middle of America?

There is SOME evidence to suggest this, more than I think is usually

acknowledged.

I found that it was less than an elaborate and systematic plan of

action. And that British opinion, public, military, political were all split in

that Autumn of 1814.

In mid‐Autumn, American negotiators John Quincy Adams and John

C. Calhoun at the peace talks at Ghent in Belgium were somewhat mystified when,

out of the blue, the British negotiators began to allude to a previously

unmentioned document:

the

Treaty of San Ildefonso.

The Treaty of San Ildefonso

‐‐‐‐‐‐ denied the right of the

now‐deposed Napoleon to dispose of Louisiana to any state other than Spain.

As historian Edward Channing said, the US was "the purchaser of stolen goods

from a known highwayman." (Brown) Strict international law would have upheld

that the US had not legally purchased the Louisiana Purchase.

John Moser, Department of History at the University of

Georgia Wrote on H‐Net:

This is true, but

that's not to say that the battle had no effect on the peace, for it in

large part determined how the Treaty of Ghent would be interpreted by the

British. Under the terms of the treaty, the British would have been within

their rights in withholding recognition of the Louisiana Purchase, or of

American claims to the Gulf Coast. Had the British won at New Orleans,

Britain would almost surely have turned the city back over to Spain. Monroe

realized this, and said as much to Madison. The net effect of Jackson's

victory, then, was nothing less than the international legitimization of the

Louisiana Purchase in the eyes of the Great Powers.

The logic of the propaganda ‐ ‐ that the General

Armstrong saved New Orleans and the Middle of America from British rule ‐ is

consistent with how military information was dealt with by the Public and Press

‐ most especially naval information of the time. For example, in the first

two months of the War, we can witness the case of US Army General William Hull and

his nephew US Navy Captain Isaac Hull ‐ the uncle tries to invade Canada and

loses everything ‐ the nephew sails out with Old Ironsides, destroys a

smaller British vessel.

The American public, faced with concluding they had either just

declared a foolhardy war, based on a failed invasion of Canada,

or a war where they were certainly going to tweak the British

bully's nose, based on this victory of the USS Constitution vs HMS Guierriere,

the American public and press, of course, opts for the latter, and a triumphant

posture.

|

|

What happened to:

OUTCOME ‐ what happened to them all? Now that I've told

you the story, I have to tell what happened to all these people:

Andrew Jackson

General Andrew Jackson’s stunning victory over crack British

troops at Chalmette on January 8, 1815, was the greatest American land victory of

the War of 1812.— the last battle of the last war ever fought

between England and the United States—it preserved America’s claim to

the Louisiana Purchase, prompted a wave of migration and settlement along the

Mississippi River, and restored American pride and unity. It also made Jackson a

national hero

Thomas Fleming ‐ one of our favorite speakers, wrote :

"He was able to parlay his popularity into a political

base of power that propelled him to the presidency in 1828. As Jackson was leaving

the White House at the end of his second term in 1837, a congressman (perhaps a

wise guy, trying to needle him?) asked him

‐‐‐‐‐ had there been any point to the Battle of

New Orleans? After all, it had been fought after the peace treaty was signed. The

old warrior gave him one of his patented steely glares and said: "If General

Pakenham and his ten thousand matchless veterans could have annihilated my little

army...he would have captured New Orleans and sentried all the contiguous

territory, though technically the war was over....Great Britain would have

immediately abrogated the Treaty of Ghent and would have ignored Jefferson's

transaction with Napoleon."

Was he right? We will never know for certain. Old Hickory settled the

argument in advance by winning the battle." again from Thomas

Fleming's article on Jackson on the web ‐ see my bibliography.

The War

'Uti posseditis', is the Latin phrase

that means "you keep what you conquered" as opposed to "status quo

ante bellum" ‐ "the way it was before the war". In the

negotiations at Ghent, America had successfully opposed Britain's attempt to

sign a treaty where they'd hold onto conquered US territory. Did they know

about the massive fleet assembling for New Orleans? And yet, Britain gave way and

agreed, in essence, to the evacuation of US Territory ‐ without any news

from New Orleans. Why?

In the Spring of 1814, the Duke of Wellington had urged a

settlement. Faced with the depletion of the British treasury due in part to the

heavy costs of the Napoleonic Wars, and privateers in British waters, the

negotiators for Great Britain accepted the Treaty of Ghent on December 24, 1814.

It provided for the cessation of hostilities, the restoration of conquests and a

commission to settle boundary disputes.

…so, the Peace Treaty was signed on Christmas Eve, 1814. Good thing,

too. The War was ruining the economies of both the UK and the US. In New York City

in early February, on a dark winter night, a ship with an American and a British

diplomat brought the news. From the downtown docks, after dark, the word began to

spread thru the icy city; candles in celebration began to appear in the windows up

and down lower Broadway.

The United States had ended hostilities without losing any

territory and asserted its status as an independent nation that would no

longer stand for the violation of its neutral rights or the humiliation of

impressment. Perhaps the best measure of the impact of the war is how

Americans learned from the experiences and mistakes of the war and applied

those lessons to postwar America. After the war the United States reorganized

the Army, Navy, and War Department to correct the defects revealed during the

War of 1812. In his message to Congress in December 1815 President Madison

acknowledged the financial difficulties caused by the lack of a national bank

and the supply problems caused by the poor conditions of American roads, and

he recognized the value of American domestic manufacturing, stimulated by the

trade disruptions of the war. Madison's recommendations that Congress

approve a national bank, federal support for transportation and internal

improvements, and protective tariffs were all enacted in the years immediately

following the War of 1812. Americans also emerged from the war with a message

to the world that their experiment in republicanism had been proven

successful.

Jayne Triber

Only the Indians, that the Treaty made some effort to consider, lost

land.

Three of our great icons ‐‐ the Star Spangled Banner,

"Old Ironsides," and Uncle Sam ‐‐ date from this war.

With the final defeat and removal of Napoleon,

impressments

as an Admiralty system was not needed and largely ceased to exist.

Though the U.S. gained none of its avowed aims, popular legend

soon converted defeat into the illusion of victory. Several circumstances

contributed to this process: the series of military successes in the

war's closing months created a sense of victory The war also marked a

decline of U.S. dependence on Europe and stimulated a sense of nationality. EB

article

It demonstrated enough resilience to force the

British to look at

the United States as something other than a

renegade colony, and perhaps helped to lay the groundwork for the

rapprochement later in the century. It may also have played a part in the

British willingness to compromise on the issue of the North West territories

in the 1840's possibly averting another war. In a sense, the War of 1812

might have ended the last external threat to the survival and growth of the

United States [the issue of slavery being an internal threat] until the

development of Soviet nuclear capabilities in the Cold War.

British Naval Commander Admiral Alexander Cochrane

While awaiting a replacement for Ross, Cochrane had commenced the

attack against New Orleans. On December 14, his forces captured the American

gunboats on Lake Borgne. The British subsequently advanced through Bayou Bienvenu

to within seven miles of the city by December 23. But the British attack on

General Andrew Jackson's army ultimately failed and Cochrane's Navy

withdrew with the rest of the British force.

He got most of the British brigades back in time for the Battle of

Waterloo.

Cochrane died in Paris on January 26, 1832.

British Army Commander Sir Edward Packenham ‐

On January 8, 1815, on the field of Chalmette, a few miles before

New Orleans, "whole platoons were mown down as with a scythe; but the gallant

army continued to press forward until officer after officer was killed, and

Pakenham himself fell, bleeding and dying…." (MOA)

He was shot by a Tennessee marksman from behind bales of cotton.

Like General Ross from Baltimore, some say, he is shipped home to England in a keg

of Jamaican rum (a variety of stories, and jokes, have spun out of this method of

preservation.) So like General Ross at Baltimore, he was shot by an American

sharpshooter and he died attended by the same staff aide as Ross, Captain Duncan

MacDougall

British man‐of‐war Captain Robert Lloyd

‐ who started the fight in the Azores. He was given

the honor of bringing back to England from the Battle of New Orleans, the body of

General Sir Edward Packenham. Before the Napoleonic and 1812 Wars, Lloyd had

earlier been, and after became again, a sheriff in Wales on the island of

Anglesey.

At one point, I found a distant cousin of my villain on a Welch

genealogy forum. In hopes of getting more, I posted a request for information.

Hoping to appear both honest and scholarly, I added in my request for more

information:

"I must now caution you that some of this research focusing

on Robert Lloyd tends to characterize him as a villain and, perhaps, as a man

who lost his temper and thus changed the course of world history. You can see

more at my website. ( http://bobrowen.com/warof1812/)

But I would hope you find it interesting as a far‐reaching tale of

turbulent times and as an unearthing of a most significant son of Anglesey. I

will apologize in advance for any residue of American jingoism in this

material from the period."

Well, it did me no good, I got no replies, and you get the feeling

the Welch are happy to leave their confrontational Royal Navy Captain behind.

Privateering in General

Today, there are known cases of piracy in the South

China Sea but as for privateering ‐

Members of NYMAS will, of course, know about

… Imperial Germany in WWI (especially the famous SEEADLER, an armed

sailing barque skippered by the humorous Kapitan and Graf Felix Von Luckner)

‐‐

and especially the Plan of Nazi Germany in WWII, in arming and

sending out numerous disguised merchantmen as naval raiders worldwide to attack

Allied merchantmen.

The United States is not a party to any instrument which explicitly

renounces privateering. The U.S. is a party to some of the Hague Conventions of

1907 which, by implicit incorporation of the 1856 Paris Declaration, have been

construed to reaffirm the principle that "privateering is, and remains,

abolished." (H‐DIPLO)

The General Armstrong

As far as I know, The General Armstrong still lies in the harbor in

the Azores, altho the Long Tom pivot gun was rescued; the massive iron

42‐pounder gun ‐‐ a monster weapon for its day

‐‐ eventually was acquired by the Navy Museum at Washington Navy

Yard.

What didn't go away for a very long time was a series of

lawsuits and claims, both nationally and internationally. In 1852, the French

Emperor Napoleon ruled against the US simply because the crew of The General

Armstrong had fired first on that evening in September in 1814.

Captain Samuel Chester Reid, Captain of The General Armstrong

‐

Whatever doubts I've cast on the mythology of the General

Armstrong, Captain Reid and his crew were very brave men and tho cornered, stood

up to an attack others would have withered under.

The hype, and I don't know what else to call it, that the

General Armstrong changed the outcome of the Battle of New Orleans, perhaps tells

us more about the psychological needs of America.

An underpopulated, new nation, fighting a contemptuous former ruling

country and King, needed to feel it had sway over wide ranging events.

Reid became harbormaster of the Port of New York in 1843. (LC) and

passed away in obscurity in Brooklyn on the eve of the Civil War in 1861.

In 1956, his unmarked grave was found at Greenwood Cemetery ‐

the Stonemasons erected an imposing monument, lauding Reid as designer of the 1818

flag and esp. as Captain of the Armstrong‐ and on the base of it, carved in

stone, is ‐

"If there had been no Battle of Fayal, there would have

been no Battle of New Orleans." ‐‐ Andrew Jackson

We've all heard that "the first casualty of war is

truth." Perhaps, in this case, it was the last casualty.

As for my ancestors, the Mackies

Frankly, I loved the idea that my

great‐great‐grandfather might have changed the course of world

history…and the idea of informing my cousin in California that if it weren't

for our ancestor, on his next trip east, he might be flying over British Middle

America.

But now I must tell you that on my last day of researching American

privateer Captain Reid's family papers at the Library of Congress, I finally

found the crew list for the fateful voyage ‐‐ and there were no

Mackies on it.

But the search launched this, to me, wonderful expedition

you've heard about tonight.

Don't know what happened to the other brother, but the first,

John Hewitt Mackie, settled initially in New London, CT, then across the Sound in

Greenport, LI. He married an Irish girl, as would his grandson. He and his son

worked as ship riggers, then the son struck out on his own, (possibly with

Congressional bounty money from the father that Reid had pressed for), and

acquired a clipper ship plying trade to China and then within China. Alas, sail

was overtaken by steam and there were possibly complications relating to the opium

trade, so that by the end of the 1800s, the family was in Bridgeport, CT and

growing children were taking jobs in factories.

It was in this era that these Scotsmen met the Irish branch of the

family. Our Irish matriarch didn't like the Scottish branch when she met them

and held that they were "adventurers and dreamers". In fact, she stood

in the way of the marriage and my grandfather and grandmother eloped. But

turn‐of‐the‐century convention reigned, they had five

children, this Mackie became a florist and they never, ever mentioned

privateering; it took John Hewitt Mackie's grandson's brother to reveal

to the young niece, my aunt, the details you heard about at the beginning of the

story:

|

Two brothers, conscripted off Isle of Skye, Scotland,

on English man of War to America.

Both brothers helped build privatier Gen. Armstrong

War 1812.

They stayed with the ship until wrecked.

|

Me? I learned that history, like Roshomon, has many points of view.

And just as Andrew Jackson, Teddy Roosevelt and the Naval

Proceedings got to spin their myth, so did I.

As for the historical legend of The General Armstrong and its effect

on the Battle of New Orleans, I am reminded of Shaw's The Devil's

Disciple. I remember well the 1959 movie version with Lawrence Olivier as

Gentleman Johnny Burgoyne who, when told he'll have to surrender to the

Americans, because of a bureaucratic error in London, is asked by his aide:

"Sir, what will history say?"

Burgoyne replies with great British arrogance:

"History, Sir, will tell lies, as usual."

Sir George Bernard Shaw,

The Devil's Disciple (1901), Act 3

END

|

|

Resources

A short Bibliography for American Privateers in the

War of 1812

On the Web

My own site with primary sources: http://bobrowen.com/warof1812/

The War of 1812 Casebook site is not to be missed,

especially the "British Views of the War of 1812 in the Chesapeake"

by Christopher T.George at http://warof1812.casebook.org/articles/dissertation.html

An absolutely splendid and detailed history on the War of

1812, causes, battles and personalities is at Galafilm http://www.galafilm.com/1812/e/index.html

(they made a four‐part TV documentary on the subject; part of what can

only be described as a Canadian renaissance of interest in the War of 1812.)

Part of MilitaryHeritage.com is their War of 1812 Website. Lots of

detail about uniforms, ordinance, and battles in the north ‐

conspicuously from a Canadian point of view.

That wonderful Tom Fleming article on Jackson is at the

Military History Quarterly website at Old Hickory's Finest Hour ‐

Cover Page: Winter '01 MHQ ...

www.thehistorynet.com/MHQ/articles/2001/winter01_cover.htm

‐ 9k

Books

Best single, small book on the War: Coles, Harry Lewis,

1918‐ The War of 1812, Chicago, University of Chicago

Press [1965]

My nomination for most readable, but good on scholarship,

is Lord, Walter, 1917‐ The dawn's early light /:

Johns Hopkins University Press, 1994. 384 p. : ill., maps ; 22 cm.

I think, by far, the best book on the Battle of New

Orleans is: Carter, Samuel, 1904‐ Blaze of glory; the fight for

New Orleans, 1814‐1815. New York, St. Martin's Press

[1971. The only trouble is Blaze of Glory may be hard to

find.

Also excellent is: :Brown, Wilburt S., 1900‐1968. The amphibious

campaign for West Florida and Louisiana, 1814‐1815; a critical review

of strategy and tactics at New Orleans. University, Ala., University of Alabama

Press [1969] xii, 233 p. maps. 26 cm.

Hickey, Donald R., 1944‐, The War of 1812 : a forgotten conflict /

Donald R. Hickey. Urbana : University of Illinois Press, c1989. xiii, 457 p. :

ill. ; 24 cm.

Recent and more popular is Remini, Robert Vincent, 1921‐, The Battle of

New Orleans / Robert V. Remini. New York, N.Y. : Viking, 1999.

Valuable for its details is Mahan, A. T. (Alfred

Thayer), 1840‐1914. Sea power in its relations to the War of

1812. New York, Haskell House, 1969. 2 v. illus., maps, ports. 23

cm.

Privateering is covered by a contemporary who actually

captained a privateer himself: Coggeshall, George, 1784‐1861.

History of the American privateers, and

letters‐of‐marque, during our war with England in the

years 1812, '13, and '14. Interspersed with several naval

battles between American and British ships‐of‐war. By

George Coggeshall ... 3d ed., rev., cor. and enl. New York, The Author,

1861. lv, 482 p. front. (port.) plates. 22 cm. Reprints available and you

can read it or download it from the splendid Making of America site at the

University of Michigan at http://moa.umdl.umich.edu/

Prof. Larry J. Sechrest apt paper Privateering and

National Defense: Naval Warfare for Private Profit is at http://www.independent.org/tii/WorkingPapers/Sechrest6.html

aa a pdf file.

Pronunciation:

Cockburn = CO‐burn

Cochrane = COCK‐run

Packenham = pack‐EN‐am

Special acknowledgements:

Don Canney, official Historian of the United States

Coast Guard.

Kay Larson, of NYMAS and National Historian of the

USCGA who took time from her schedule to help with myriad issues.

Philip S. Goodman's for his invaluable

assistance and guidance.

Frank Radford for his Naploeonic expertise on the

British and European perspectives.

Norman Brower of the South Street Seaport Museum

Library helped pinpoint detail of the era.

Altho Norman Friedman has dozens of books on naval

history to his credit, he was kind enough to give this amateur history

buff direction.

Bob O'Hara, who lives in Kew, London, outside

the gates of the Public Record Office, and is a top professional

researcher.

Thanks to Joseph C. Abdo whose paper from the I

Congresso Internacional de Estudos Anglo‐Portugueses 6‐8

Maio de 2001 Lisboa on the US Consul Dabney's family was an

important resource.

And to Alice Galassi, great‐granddaughter of

the General Armstrong's valiant Captain Samuel Chester Reid.